Prof Chris Wanjala, a public intellectual with a difference

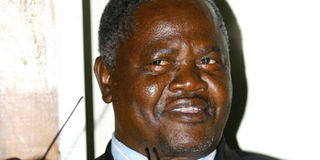

The late Prof Chris Lukorito Wanjala. PHOTO | FILE

What you need to know:

- To Prof Wanjala, one became a scholar only after obtaining the PhD and, before that, one was a novice or greenhorn who needed to be guided, a position I did not agree with.

- Prof Chris Wanjala and I did not agree on many issues.

The death of Prof Chris Lukorito Wanjala has robbed Kenya of yet another intellectual giant who towered in the literary world as a major critic.

Prof Wanjala was a public intellectual with a difference and never made any academic debate become personal. He never attacked the character of a person but his ideas.

I knew Prof Wanjala through his commentaries in newspapers before I joined the University of Nairobi in 1986. He wrote in tough English and liked to quote Shakespeare and Charles Dickens.

Prof Wanjala’s pen was fiery and poured out a lot of intellectual vitriol, especially to those who did not have PhDs and pretended to be intellectuals such as David Mailu and Meja Mwangi.

To Prof Wanjala, one became a scholar only after obtaining the PhD and, before that, one was a novice or greenhorn who needed to be guided, a position I did not agree with. Prof Chris Wanjala and I did not agree on many issues.

ACADEMIC HEAVYWEIGHT

I joined the University of Nairobi in 1986 when Prof Chris Wanjala was already a professor and one of the academic heavyweights on campus. He had intellectual clout and many scholars feared and also respected him.

His articles in the dailies raised a lot of debates and he loved it and would often respond to comments about them with his trademark mischievous laughter.

If I had done literature, he would have taught me. My University of Nairobi year mates such as David Matende, Manoah Esipisu, Kennedy Buhere and Elphas Eshiuchi were always full of praise of his intellectual prowess and fortitude.

Prof Wanjala was a student of Prof Ngugi wa Thiong’o but he, in turn, mentored many students through his guidance such as Prof Peter Amuka, among others.

When I was Deputy Vice-Chancellor at Kisii University, I invited Prof Wanjala and Prof Peter Amuka to discuss Ngugi’s presentation when he came to Kisii University. I wanted Ngugi’s academic son and academic grandson to share a platform and succeeded in doing so.

I found Prof Wanjala agreeable, approachable and easy to get along with, except that he came across as not your ordinary type of professor because he liked polemics and grandstanding, which often put him at crosshairs with many colleagues such as Prof William Ochieng and Ali Mazrui and myself.

'ACADEMIC CURSE'

I often took on Prof Wanjala and Prof Ochieng publicly but not very successfully because they were my academic parents and you can only go that far or risk an academic curse.

He occasionally teased me in his writings and social commentary, the last of which was last year when he accused me of holding conferences in my village which was, of course, not true.

I chose not to respond publicly in order not to cause escalation as any expert on peace and conflict would tell you. We got along quite well and I even invited him to one of our annual international conferences in 2016 as keynote speaker.

In 1989 when I was a master’s student at the University of Nairobi, I witnessed an interesting discussion between Prof Chris Wanjala and visiting Nigerian writer Cyprian Ekwensi at the Education II Theatre.

The debate centred on whether a person without a PhD should teach at the university or not, and whether books written by someone without a PhD such as Ekwensi should be used as texts at university level.

During the discussion in 1989, Ekwensi was very angry with Prof Wanjala for asking this question on PhD and the chair of the session, Prof Henry Chakava, could not bring the two intellectual giants to agree.

I liked Prof Wanjala’s demeanour and almost jocular manner in which he stoked the fire to the chagrin of some in the audience.

Mr Ekwensi confessed that the only writer of repute he had heard about from Kenya was Prof Ngugi wa Thiong’o and wondered aloud who Prof Wanjala was.

Ekwensi said he would not listen to any other person for guidance but Ngugi. He listed more than six of Ngugi’s novels and said he had read and liked them especially The River Between. He said he knew and admired Ngugi. He also admitted he had read some works by Kenyan writers such as Meja Mwangi especially Going Down River Road, Kill Me Quick and The Cockroach Dance.

He said he did not know and had never heard of the professor who was now crucifying him for not having a PhD. He said he had not come to the university to seek a PhD but had come on the invitation of his publisher, the East African Educational Publishers, of Mr Henry Chakava.

But Prof Wanjala handled the situation well insisting Ekwensi would be a better writer if he earned his PhD and that it was not late, to the amusement of everyone. As the exchange raged, members of the audience started to take sides.

They were agreeing it was wrong for Prof Wanjala to take on Ekwensi on an issue that was not part of the agenda.

'COULD DEFEND HIMSELF'

But Ekwensi would not allow anyone to come to his rescue, arguing that he could defend himself in any intellectual debate. He said his novel, Jagua Nana, had been popular and sold more than one million copies and had been translated into many languages across the world. He also mentioned how his other novel, People of the City, had also received great acclaim.

The session ended well and we had enjoyed one of the extraordinary intellectual debates on our campus.

Prof Wanjala was one of the major intellectual minds behind Africanisation of African studies. He admired the works of Cheikh anta Diop, particularly his masterpiece African Origin of Civilisation: Myth or Reality.

The argument Diop advanced in this book by stating “ancient Egypt was a [Black] civilisation" was penetratingly compelling as it was exciting and turned European and Mediterranean studies heads down.

It caused academic ripples and made many scholars to rethink the whole notion of Egyptology, which was taught as part of European history and literature in some universities in Europe and North America.

Prof Wanjala was part of the “revolution” at the University of Nairobi who changed the name of the department to reflect the new independent status and started courses such as East African Literature, Oral Literature, among others.

Prof Wanjala had great intellectual courage, participating in what he believed in regardless of what others thought about it, such as his membership of the Youth for KANU 92, which was then regarded as an outfit of the blue eyed boys of the system.

He knew how to stand his ground. He was a great debater and one that worked with facts rather than empty rhetoric and innuendo.

Prof Wanjala will be remembered as being part of the young intellectual productivity in East Africa in the 1970s and 1980s that included Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Micere Mugo, Okot P’Bitek and Taban lo Liyong. He was a pioneer in many ways and in his teaching; he often elicited the literary prowess of fellow pioneers such as Chinua Achebe, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Wole Soyinka, Elechi Amadi and John Rubadiri.

He taught us how to cite fellow African scholars. He will be remembered for producing a great number of PhDs compared to his contemporaries.

***

Prof Amutabi is the Vice-Chancellor of Lukenya University; Professor of History and Fulbright Scholar [email protected]