President Paul, Journalist Paul and the careers of our dreams

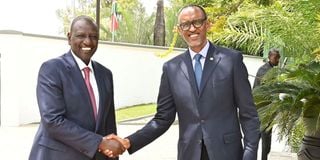

President William Ruto and his Rwandan counterpart Paul Kagame during a state visit at the Office of the President in Kigali, Rwanda on April 4, 2023.

General Paul Kagame of Rwanda announced recently that he intends to step down soon from the Presidency of his country.

He made the announcement at a joint press conference in Kigali with his guest, President William Ruto of Kenya. It is, indeed, remarkable for a sitting African President to voluntarily step down from the lofty seat at the relatively youthful age of 65, and after only 23 years in power.

But that is not the main reason why I am writing about Kagame’s announcement. After all, you know my frigid dread of politics, especially African politics.

Rwandan developments, however, have many reasons for grabbing my attention. I have, for example, told you of my Rwandese blood relatives, and my conviction that Rwanda and Uganda are, and have always been, inseparable.

Then, there has been my lifelong love affair with the land of a thousand hills and its people. My first girlfriend, Rosa Nyanzira, whom I befriended when I was four or five years old, was Rwandese.

I have been visiting Rwanda since 1969, my first mission being a study and research trip to the National University at Butare, and Kansi Seminary.

There, I sat at the feet of the famous Rwandese scholar, Abbé Alexis Kagame, one of the earliest modern formulators of the “Ubuntu” philosophy. Decades later, in 2006, as I might have mentioned to you, I accepted an academic appointment at one of the higher institutions of learning in Kigali.

Although my stay in Kigali was cut short mainly by health issues, my intention to contribute to Rwanda’s post-genocide reconstruction, alongside other international professionals, including many Kenyans, was genuine.

What, however, grabbed my attention about President Kagame’s announcement and really got me pricking my ears was the hint he dropped about his post-presidential plans. “I am sure one day,” said the President, “I may join journalism in my old age.”

Restrained expression

The Rwandese President is characteristically a man of rather restrained expression and he is not lavish with his jokes. So, we cannot assume that he was saying this just to humour and flatter the large press corps at the conference.

Apparently, most of those at the press conference, and those of us who followed it later, chose to take him seriously at his word, both about his envisaged retirement and also his future career.

This process of interpretation is what particularly interests and intrigues semiologists and semioticians. For them, and their science of semiotics, an utterance like “I may join journalism” is only a coded stimulant. Its recipients, the readers or hearers, must systematically decode it, taking into account all the circumstances in and around its release, as well as our knowledge of the world, in order to have it signify or make meaning.

In other words, texts or utterances, whether political or biblical, do not “say”. We make them say or mean by the elaborate, semiotic process of interpretation. Thus, for the pure, strict semiotician, in communication, there is only interpretation. But I digress.

Having interpreted the Rwandese leader’s utterance about journalism as a serious intention, we are still left with a plethora of questions and speculations. What kind of journalism, for example, does General Kagame intend to practice?

Does he want to be a reporter, an investigator, an editor, a news anchor, a commentator or a media mogul? “Journalist” and “pastor”, as you know, are two identities that are increasingly and indiscriminately claimed by all sorts of characters, to the annoyance and chagrin of genuine practitioners of the professions.

Be that as it may, President Kagame’s desire to join journalism as the pursuit of his later years underlined for me the familiar dialectic between the careers we dream of and the careers that we actually pursue, often for most of our lives.

You know the progression from our childhood fancies of “I want to be a tractor driver when I grow up” or “I want to be a teacher and charaza (whip) the naughty children” (when the notorious cane was still allowed into our classrooms). Based on the few role models around us, these fancies quickly evaporate as we get exposed to the wider world and discover more about our aptitudes.

By the time we finish high school and get into university and other institutes of higher learning, our prospects are more realistically narrowed down to the few choices towards which our education has pointed us.

Indeed, many of the disciplines which we pursue at tertiary levels more or less determine the careers we are likely to pursue most of our lives.

Those in education become teachers, the ones in medicine become doctors and the mass communication graduates will presumably become “journalists”. That, however, does not completely erase the longing for our “dream” careers, even childhood ones.

A judge who retires to his farm after decades at the bar and the bench may still drive a tractor. My childhood desire was to be a churchman, a priest. It did not materialise, as I gravitated more and more towards languages, letters and education. Upon graduation, I had three main careers open to me: academics, publishing and diplomacy.

This last one I never really tried for, but I did interview for publishing, although the sheer pressure of my immediate teachers and associates, like the late Arnold Kettle and Emile Snyder in Dar es Salaam and David Cook at Makerere, eventually won me over to academics.

Luckily, I have lived long enough to pursue that career to retirement and even have a few more years to devote to my other fancied jobs, like creative writing and even “journalism”.

(I smile mischievously when people describe me as a journalist because I write for the papers). Maybe I will also be blessed with another few years to practise as a priest, or at least a lay preacher (not a pastor), as I had always wanted to.

What dream job would you like to try your hand at before you finally call it a day?

Prof Bukenya is a leading East African scholar of English and [email protected]