Of Sundiata, God’s Bits of Wood, magnanimity and equanimity

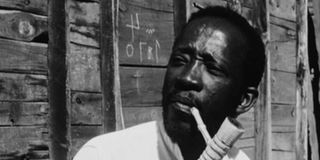

Senegalese all-around creative Sembene Ousmane.

What you need to know:

- Magnanimity is, thus, the quality of being big-minded, big-hearted, and generous.

- Equanimity means the ability to accept and deal with whatever comes one’s way with calmness and composure.

- Anyone entering a contest, like the countrywide exercises we have just had in Kenya, should arm themselves with these two virtues.

“Return to your books.” This is a piece of advice given, dismissively, by one character to another in Emily Brontë’s novel, Wuthering Heights.

Catherine, a sickly and neglected wife, says this to Edgar, her nerdy husband, to signal the end of their relationship.

I, however, thought I should return to my books in the light of the amazing events unfolding around me.

After all, books are one of the few things I know anything about, and through which I can organise my thoughts.

Thus, though I cannot help thinking and talking about the goings-on, I decided to talk about them through the lens of a few of the books that I love.

But before I tell you about the books, let us get hold of these few difficult words. The theme of my chat today is magnanimity and equanimity in a contest.

In other words, when you go into a competition, you should be prepared to be magnanimous and “equanimous”. That is where the big words come in.

Generosity

“Magnanimous” simply means “generous”. Its literal meaning, from its Latin origins, is big (magna) mind (anima).

Magnanimity is, thus, the quality of being big-minded, big-hearted, and generous. We note here that “generosity” is not limited to material goods.

It extends to social spaces and includes such graces as open-mindedness, acceptance, tolerance and inclusion.

“Equanimity” also has “anima” (mind ) in it, but the emphasis here is on the first part, “equa-“, of this compound term.

That part suggests level-mindedness or level-headedness. You can easily relate that bit to terms like “equal, equality or equity”.

The Latin language seems to have looked at our human affairs as being on a pair of weighing scales (mizani in Kiswahili).

When there is a balance between two sets of objects, events or circumstances, you would have “equitas” (equity).

As a state of mind or an attitude, equanimity is an admirable and desirable virtue.

Equanimity means the ability to accept and deal with whatever comes one’s way with calmness and composure.

This ability is succinctly suggested in two lines of Rudyard Kipling’s famous poem, “If”. He praises the ability to “meet disaster and triumph, and treat those two impostors just the same”.

Equanimity is probably what lies at the root of the philosophical doctrine of stoicism.

The stoics are not necessarily pessimistic, but their approach is that, in life, good things and bad things will inevitably come our way.

Emotions

The best way to prepare to deal with them is to take them without unbridled emotions.

A friend of mine suggested in a social media post that we can take this even further by always exploring how we can turn every negative event in our lives into a positive opportunity. Quite a tall order that, but not an impossible one.

Returning to my theme, magnanimity and equanimity in a contest, I suggest that anyone entering a contest, like the countrywide exercises we have just had in Kenya, should arm themselves with these two virtues.

They would prepare them adequately for the outcome of the contest, victory or loss.

The principle is that we should be magnanimous in victory and “equanimous” in a loss.

My computer did not seem to recognise this last term, but I googled it out and even got the pronunciation for it.

It describes a person in possession of equanimity, as we defined it above.

Every contestant, especially in leadership roles, should arm themselves with these qualities because, obviously, the contest can go either way, ending in loss or victory.

The victor should be magnanimous by, first of all, respecting and, indeed, thanking their competitors instead of crowing over them, deriding them or excluding them from the activities over which they were contesting.

We have heard quite a lot of magnanimous statements from the declared winners of the Kenyan contexts this week.

The hope and challenge are that we will see the declarations translated into concrete and consistent action.

Remember, your fellow contestants were not “enemies” but rivals, challengers or opponents.

Equanimity is the pillar of a good loser. It starts from the understanding that in every contest there is a winner and a loser.

No shame

There should be no shame, anger or sorrow in losing to a deserving competitor in a fair and transparent contest.

Secondly, losing a contest, like an election, is by no means the end of the world.

After all, there will be many more such contests before you bow out of this life. Moreover, not winning a political office, for example, leaves you free to do myriad other things, probably much more enjoyable and significant to you than being an MCA, Senator or Governor.

Above all, “Blessed is the person who does battle without bitterness”, as I remember the refrain from the performance of the Sundiata Epic narrated in Ousmane Sembene’s God’s Bits of Wood (Les bouts de bois de Dieu).

Sembene’s novel, as you may remember, fictionalises the late 1940s industrial action by African workers across several West African countries, protesting against French colonial oppression and exploitation.

The strike was a precursor of the later independence struggles but Sembene subtly alludes to the main epic of the region, the heroic narrative of the exploits of the founder of the ancient Mali Empire.

We who were reading God’s Bits of Wood in the late 1960s and early 1970s easily connected it to D.T. Niane’s Sundiata, the full transcription and translation into French (and eventually English) of the performance of the epic by the griot (poet) Mamadou Kouyaté.

Distant memories, indeed, but those are the fruits of old age. Thinking of Ousmane Sembene, for example, reminds me of the hunch I had on reading my Mwalimu Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s Petals of Blood that it was significantly influenced by God’s Bits of Wood. You may want to have another look.

Ngugi wa Thiong’o is, of course, a shining example of a person who has fought his many battles with equanimity and without bitterness.

Prof Bukenya is a leading East African scholar of English and [email protected]