Lessons from Okot p’Bitek’s ‘Lawino,’ 1966 and all that

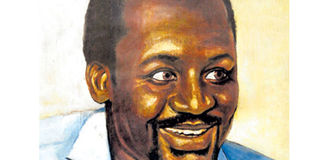

Okot p’Bitek's lyrical dramatic monologue, Song of Lawino, which first appeared in English in 1966. ILLUSTRATION | JOHN NYAGAH

What you need to know:

- Anyway, that is 1066 and all that. The “sixty-six and all that” struck me with a particular poignancy as I joined the august assembly of scholars, writers and other literary and cultural luminaries at Makerere to celebrate the appearance of Lawino in 1966.

- The star guests were members of Okot’s family, led by Jane Okot p’Bitek, his daughter, a prominent lawyer, who has also penned her own extended work of verse, Song of Farewell.

- Among the international scholars gracing the occasion were Taban lo Liyong, a lifelong acquaintance of Okot, Leslie Ogundipe, whom most 1970s learners of English will mostly remember as one of the authors of the famous secondary English course, and the Kenyan American literary guru, Simon Gikandi.

I promised to tell you of Lawino and her husband Ocol’s golden jubilee celebrations at Makerere on March 18. Ocol, in Luo, means the dark-skinned one, or simply, Blackie. Lawino, or Kawino, in some Ugandan languages, means jewel or decoration. You will also remember that the Ocol homestead is a ménage á trois, a three-pronged or “triple couple”, since there is Clementine, the woman with whom Lawino shares her husband.

All three, and the rest of the cast of a thousand others are, of course, imaginative creatures of the mercurial Okot p’Bitek in his lyrical dramatic monologue, Song of Lawino, which first appeared in English in 1966. Thus, in all academic propriety and decorum, I mention author, title and year of publication in my heading above. But you may wonder why I add “and all that”.

It is almost instinctive for English speakers, whenever they mention a date ending in sixty-six, to throw in the tag “and all that”. This derives from the title of a book, Ten Sixty-Six and All That, about the year 1066, when William the Conqueror, a French adventurer from Normandy, staged a successful invasion of Great Britain and established himself as King out there. The title was popular among us colonial schoolchildren, and it passed into popular parlance.

Anyway, that is 1066 and all that. The “sixty-six and all that” struck me with a particular poignancy as I joined the august assembly of scholars, writers and other literary and cultural luminaries at Makerere to celebrate the appearance of Lawino in 1966.

FINDING GREATNESS

The Makerere event was billed as a symposium, at which the literati would share their experiences and views of Song of Lawino and of Okot p’Bitek’s work and influence, in general. I thought it had been rather underpublicised by the organisers, the Makerere Institute of Social Research and the Department of Literature. Chris Wanjala would probably have said that that was characteristic of Makerere’s inherited Great “English” Tradition of understatement.

But as it turned out, the attendance was quite impressive, including such Ugandan notables as Timothy Wangusa, Arthur Gakwandi, Goretti Kyomuhendo, Laban Erapu and Julius Ocwinyo, all scholars and creative writers in their own right. Prof Charles Okumu, my former student, who is working on a much-anticipated biography of Okot p’Bitek, was also in attendance.

The star guests were members of Okot’s family, led by Jane Okot p’Bitek, his daughter, a prominent lawyer, who has also penned her own extended work of verse, Song of Farewell. Among the international scholars gracing the occasion were Taban lo Liyong, a lifelong acquaintance of Okot, Leslie Ogundipe, whom most 1970s learners of English will mostly remember as one of the authors of the famous secondary English course, and the Kenyan American literary guru, Simon Gikandi.

Prof Gikandi, from Princeton, delivered the keynote address, in which he highlighted the international qualities of Song of Lawino that have ensured not only its enduring popularity, but also its global appeal, even across translations. Indeed, Lawino seems to have thrived on translation. The English translation of the poem appeared before the Acholi ‘original,’ Per pa Lawino.

Speaking of translation, I found greatness thrust upon me at the symposium when I was asked to introduce Omulanga gwa Lawino, Abasi Kiyimba’s Luganda translation of Song of Lawino. Prof Kiyimba, who worked on his text for well over a decade, happened to be indisposed on the day of the symposium, where his text was being launched as one of the events marking the 50th anniversary celebrations.

He picked on me to represent him at the launch, not only because I am a Luganda speaker, but also, I suppose, because I am a fellow UDSM alumnus. More seriously, however, the good professor had consulted me extensively during the early stages of his translation, and he has actually included some of my comments in the prefatory material to his work, making me feel pretty flattered.

I could have spent most of my brief moment in the limelight expatiating on my connections with Abasi Kiyimba, on whose young shoulders the mantle of Oral Literature at Makerere seems to have fallen after I left in the late 1970s. Or I could have dwelt on my many “run-ins” with p’Bitek, whose last chair as Senior Creative Fellow in Literature I inherited on my return to Makerere.

IMPORTANT ASPECT

I decided instead to use the opportunity to remind the audience, which included a large number of young high school readers, of three points we should keep in mind when we face the Lawino text. The first is not to assume that Okot was speaking for himself, “defending African culture.” Far from it, the wily poet creates a character, Lawino, with all her limitations, prejudices and self-interests, whose voice we hear throughout the dramatic monologue.

Secondly, we should not claim that Okot was against “European culture”, or any culture for that matter. What he was probably targeting was what he calls “apemanship” in one of his essays in Africa’s Cultural Revolution. In other words, we should not ape or imitate habits, fashions or styles just because other people follow them or say they are good. We should have a reason for living the lifestyles that we live.

Thirdly and most importantly, Okot was inviting us into a dialogue. Culture is an important aspect of our lives and societies, and we should seriously engage with it, and with one another about it. This became even more apparent with the publication of Song of Ocol, an apparent rebuttal of Lawino, which left many single-tracked readers disconcerted, if not downright confused.

But all that Okot was doing was to show that there is always more than one way of looking at a situation. He was demonstrating in practical terms what we in literature call “dialogism”, as Prof Kimani Njogu would tell you.

Back to 1966, that was also the year I fell deeply, desperately and maybe irredeemably in love. But I am sure I will need more time and space to dialogise about that.