Author on false narrative that Kenyans do not love reading

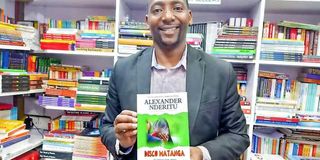

Author Alexander Nderitu with his latest book, ‘Disco Matanga.’

Alexander Nderitu is an author with five books to his name. He is a pioneer of e-books in Kenya. For his efforts in writing and other artistic works, he was included in the Business Daily’s Top 40 Under 40 in 2017. He is the very exemplification that self-publishing actually pays. He recently released a new book, Disco Matanga, which is doing well in the market. He spoke to MBUGUA NGUNJIRI about his writing and the state of publishing in Kenya

What moved you to write Disco Matanga?

Jeffery Archer was the inspiration for this one. I’ve loved his short story collections since high school …But I am an African scribe and I wanted to wade into the highly popular romance genre. So the goal behind Disco Matanga, crazy as it seems, was to write something that reads like a Jeffery Archer but written by an African griot by way of Barbara Cartland.

How many books have you written so far?

When the Whirlwind Passes (2001); The Moon is Made of Green Cheese (2008); Kiss, Commander, Promise (2021) ; The Talking of Trees (2021); Disco Matanga (2022)

How are they doing in the market?

Disco Matanga is currently the most profitable, followed by When the Whirlwind Passes. Kiss, Commander, Promise is my most underrated work by far. Like Disco Matanga, it’s a collection of short stories. In my opinion, it’s my best work after Disco Matanga. An Amazon buyer described it as ‘an unexpected delight’. But for some reason, it doesn’t resonate with Kenyan buyers like my other books.

Does writing pay, in Kenya?

Yes, but we still don’t have the literary ecosystem to make it sustainable as a career for most scribblers. Covid-19 made things worse. You don’t see many book festivals, discussions, literary salons, author interviews, college lectures, book drives, book launches, and so on. One can sell more books at events than via bookstores. One Nairobi bookstore admitted to me that they are basically “stockists” – authors and publishers do all the marketing.

Do Kenyans read?

Yes, and the reading public is growing, as evidenced by the explosion of book clubs in recent years. The problem had to do with literacy. Books were not invented in Sub-Saharan Africa. We had oral literature and other cultural things. The missionaries set up schools and started educating Africans. As literacy grew, so did the reading culture.

Who/what inspired you to venture into writing?

The universe decided that I would be a scribe. I was literally born on William Shakespeare’s birthday (April 23), which also happens to be UNESCO’s World Book & Copyright Day. I was destined for this. I didn’t choose writing, writing chose me!

Who inspired the other; you or your sister?

Neither. Our genres are very different. I am a storyteller, she’s a poet. I’ve noticed that even the majority of my poems are narratives.

What is your view of the state of Kenyan writing, particularly by the younger generation of writers?

The new generation of Kenyan scribes are on fire. I’ve had the opportunity to interact with and mentor some of them. Most are now in their mid-20s to mid-30s and they have brought vibrancy and hope to the post-Kwani? era. It’s hard to predict what the future holds – remember Covid-19? – but with IT, digital printing, social media and more global interconnectedness, it’s likely they’ll reach new heights.

What is your experience with publishers?

As I young man, I was in despair with the local ones because they only seemed interested in textbooks. Now we’re in hugging terms because we understand each other better. One must seek out the right publisher for their work and have a proper understanding of how the publishing system works. Young authors get impatient and emotional and mudsling publishers for being slow or aloof or not promoting their book enough or whatever.

You have to remember that the publisher is dealing with hundreds of titles and dozens of authors. They can’t focus on one guy. Also, as they have been at pains to point out over the years, they are purely businesspeople. The publisher just wants to sell enough books to make a profit. Period.

They may as well be selling sodas or avocados or toilet paper or cement. A publishing house is a company. By contrast, most scribblers (especially young ones) are artists. They want fame, recognition, awards, travel opportunities, public lectures and so on. While it’s possible for all that to happen, it is not guaranteed. And literary success usually comes after many, many years in the business. Publishers are realists.

How tough is it to market your books?

When the Whirlwind Passes was the first book I self-published. Because it was an e-book, I marketed it online – e-mails, blog posts, and things of that nature. It got some publicity as digital literature was unheard-of in the early 2000s. Even Amazon Kindle didn’t exist. Social Media and the Internet are still my biggest marketing tools.

What has been your best moment as a writer?

I have been writing for two decades so I have several highlights, including being an e-book pioneer, winning a ‘Top 40 Under 40 Award’, being on the cover of two magazines, giving a keynote lecture at the magnificent USIU-Africa library, being translated into foreign languages, and my poetry being broadcast by international media stations.

What keeps you going as a writer?

It’s in my bones. I love entrepreneurship, sports, music, food, fashion and so many other things, but nothing excites me more than literary stuff. I will Google a famous writer’s net worth before I ponder Lionel Messi’s. I am on record as saying I would rather meet bestselling novelist James Patterson than US President Joe Biden, although I like both of them.

Which Kenyan authors have had the most profound effect on your writing?

Ngũgi wa Thiong’o, especially in terms of promoting vernacular literature. I write in both English and Gikũyũ. My first Gikũyũ poetry book, Mathabu Ma Carey Francis (“The Mathematics of Carey Francis”) is in progress, though I have been reciting some of the poems in public for two years.

What are you currently working on?

A couple of plays, some poetry books, short stories and two novel manuscripts. I’m very prolific. I will be releasing a collection of African-based crime stories, titled A Body Made For Sin, early next year.

What was your worst experience in the course of your writing career?

Over the years, I became overeager to help aspiring writers. I hooked them up with media interviews, put them on TV, invited them to discussion panels, recommended them for fellowships and workshops, and so on. I received very little gratitude. Mind you, I did all this for free. A friend told me that “people don’t like to admit they were helped”. In that case, I was a fool and should just have let them achieve their milestones on their own.

I recently read an article in the Saturday Nation by Tony Mochama. In it, Nobel laureate Abdulrazak Gurnah says he struggled for “eons” to get a literary agent and he now refuses to represent anyone but himself. Wisdom detected. It’s time for me to put aside the Messiah Complex and focus on my own projects. Punda amechoka! (“The donkey is exhausted!”)