Needed urgently: Therapy for all who witnessed protesters’ deaths

Signposts denoting Kenyatta Avenue and Kaunda Street in Nairobi bearing stickers with the name Rex Masai, who was allegedly killed by the police during the anti-Finance Bill demonstrations.

What you need to know:

- Our national fabric is torn and it will take more than a few fine tailors to sew it back together.

- Is it even proper to call it grief when the person who died is someone I never met?

Where was I?

I was in school, about to clear my fourth year at Moi University. It was early January, and my then-girlfriend had got us one of those campus jobs because I had just started my soft boy era and my hedonism demanded to be taken care of.

The clatter of the university had become the soundtrack of my life: ideologies of patriotism and nationalism and all the -isms of unblemished youth and talks of let’s “make the world a better place”—the ubiquitous campus cliché.

The semester was at its climax, and all that mattered then was sherehe, promising each other “I know a guy in gava” for internships and preparing for the real world. I didn’t know the real world would come to me.

My phone had been ringing, but you know how it is. On campus, we only pick calls that start with “Jaymo Plug wa Viatu”; “Brayo wa Maform” and “Suzie Baddie”. I was what? Smack in the middle of my 20s. And what do we do in our mid-20s? We think we have time and therefore reject (not amend) every call with a “nitakupigia.” Sometimes we never call back. I didn’t. I should have.

When I did eventually call back, my mother had left a few threatening messages that bordered on disinheritance. I waved it off. I shouldn’t have. Good judgement comes from experience. And a lot of that comes from bad judgement. Turns out, there was a tragedy at home, and I had missed it.

My younger brother had died. And not just any brother, the most energetic in our family. You know the one no one thinks could go?

Yeah, that one, as if death has any respect for the labels we put on people. We were as alike as Eddy and Edith: what in him was joy and exuberance, in me was wistfulness and caution. What in one used to make you nervous, the other used to put you at ease. In other words, he was—problematic metaphor aside—the life of the family. I just didn’t know his was getting snuffed away.

Encountered death

I’ll spare you the details of what led to his death, but I never got to deal with it. I buried him in the crevices of my heart, next to all the ex-girlfriends who promised, “Mi sitawahi kuacha, babe.”

At his funeral, I remembered how he and I rarely spoke. Now he was silent forever. His body was there, but he was not. I thought how small, how helpless he looked, how death was more merciful than life.

Why, Shadi? Why? I asked. Why couldn’t you wait? Where are you going, Shadi? His spirit could not have gone far. He could hear me. Didn’t our elders teach us that death was only a curtain? That the dead aren’t really dead; they are just on the other side, watching, listening?

But underneath that thin soil of my own life, I was crumbling. Life is a distraction, a show that diverts us from the emptiness of reality.

So, I served myself what the Germans call kummerspeck, or grief bacon—a deadly reminder of the human condition. It’s only in 2021 after the slings and bows of adulthood that I started confronting my demons, after years of talking to them, I started talking about them in a therapy chaise lounge. I tell people, therapy saved my life.

We don’t know it yet, but the events of the past couple of weeks in this country are catastrophic. We shall never be the same again. If you were on the streets during maandamano, you probably encountered death. If you are on X, you definitely had a brush with it. Our national fabric is torn and it will take more than a few fine tailors to sew it back together.

Grief changes you. We may not agree on many things, whether it is “weuh!” or “wueh!”, “manze” or “maze!” but we can all agree that we have lost something innocent about our country. It’s a social media meme that we used to make fun of our parents watching the news, when they would commandeer the remote and dismiss our concerns saying: “Hebu weka news. Tunaweza pata nchi imeuzwa na tuko tu hapa.”

Now, I understand. I am tuned in. I remember this one joke in the Harry Potter book, “Listening to the news? Again?”

And Harry replies, “Well, it changes every day, you see.”

Waves of grief

My people say the cobra that blocks the path is going his own way, yet people run from him when they see him. That is how I see loss.

Grief. We try to run away, but it’s going its way, sure enough that we shall meet it down the road anyway. Perhaps we will pine for the country we lost. And we will move on with this anger in our hearts, this pain manifesting itself as rage. We will become less trustworthy of each other, and cling to the image that it’s them, not us, it’s the monsters and moral outliers that got us here.

For if we do not, then we have to face the fact that perhaps ordinary people, the ones who plug you on the latest shoes and buy avocados za Kisii and drive “wine-red” Nissan Jukes are capable of doing horrible things to each other—then we do not have to face the much more terrifying possibility that they are schmucks like us—and that we are schmucks like them.

Every now and then, I am reminded of my brother’s death. Perhaps I meet someone who shares a name like him, or a child who looks like him, or sometimes, he just intrudes on my thoughts. Grief, then, rises like a serpent rearing its head not only better to survey its foe, but to intimate its menace.

It’s been six years since my brother died, and constant grief is no longer my companion. Now, I am a person who lives with waves of grief. Not constant grief, but still, waves of grief.

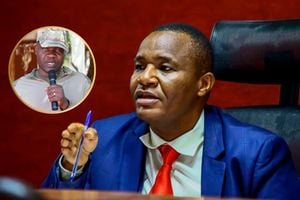

Some of those I grieve are people I didn’t even know. Beasley Kamau. David Chege. Eric Shieni. Rex Kanyike. Is it even proper to call it grief when the person who died is someone I never met? Probably not. But when I remember that Beasley Kamau or Rex Kanyike or Eric Shieni could have been my younger brother, it feels exactly like grief. Because heartbreak is the price you pay for love.

Where was I?

I was in the streets when they died. Their families lost someone that day, and the nation lost something that day.