Why Electina and Honda should return to their father, Tocla

If you remember very well, after Fiolina was irregularly fired from the big company in Kakamega, and she joined me in the village, the children – Electina, Honda and Sospeter - remained in Kakamega, as they were in school, and we agreed to let them complete first term there and join Mwisho wa Lami’s schools from second term.

Although we never discussed this, I would hear Fiolina tell people how we also planned to have her come in early to prepare the environment for the kids before they arrive.

“Baba Watoto felt that unless I come here and make the place conducive, the kids will struggle adjusting,” I heard her severally tell guests. I never corrected her, although I realize that I should have corrected her. The statement was wrong on two fronts. First of all, we have never discussed that. The kids were born and raised in Mwisho wa Lami, and only were in Kakamega for just about a year, there was really nothing to adjust to.

Secondly, I was Baba Mtoto, not Baba Watoto. We all know that only Sospeter is my child. Electina and Honda are my brothers in law, Tocla’s children while Branton is Catherina’s son. His father is only known to the mother.

Anyway, as soon as schools closed, the three – Electina, Honda and Sospeter, travelled to the village. Fiolina had organised a lorry to carry the things from her house in Kakamega; and that is where the problems began. The sofa seats, for one, could not fit into my mansion’s door regardless of how we tried. Fiolina cried when I called Nyayo, who arrived with a saw and cut off some parts for the seat to pass through the main door.

“Do you know how much I bought that sofa set for?” she asked as Nyayo went ahead. We ignored her. If you remember, I had told her to sell some of the household things, but she wouldn’t listen to me. There was a fridge, toaster, microwave, washing machine name them. What would she do with a washing machine in Mwisho wa Lami for example?

More problems arose the next morning. We had argued over what breakfast would be made. While Fiolina what to do eggs, toasted bread, tea, and fruits. I told her that was not a good idea and proposed (sugarless) porridge.

“We need to be realistic and let the kids know that life has changed, we are no longer able to afford the luxuries you accustomed them to,” I said.

“No Dre, these are children, why subject them to trauma? And aren’t eggs laid by chicken, we are not buying them, are we?” asked Fiolina.

“We just cannot throw eggs for breakfast. And when did Africans start taking eggs for breakfast?” I asked.

Anyway, I won the argument. Not really won, but I overruled her, and ordered the house girl who had come from Kakamega with the kids to prepare porridge, after I had hidden all the sugar.

“What is this?” Sospeter asked when breakfast was set, adding that it was impossible to swallow.

“I thought we would have cereals for breakfast,” said Honda when she arrived. She too refused to take the porridge.

“We have been surviving on tasteless porridge in school only to come home and find worse porridge, even the one at school had some sugar. I am not boarding,” said Electina.

Branton had no such problems. He took the porridge with zero complaints, even though I would later discover that he had hidden some sugar which he would put in his porridge.

Lunch was rice and beans, and although the Katch Kids (that was their new name) complained that it should have had meat, they ate a little. Branton had a field day and ate everything they left.

I shared the experience with Pius, my brother who was in Nairobi, who told me that I was on the right track. “Life is difficult in Nairobi, and I am also thinking of bringing my kids to the village, thank you for leading the way.” He, however, advised on something.

“You need to let the children know early that they will be going to school in the village going forward. Do not ambush them.”

I had proposed Ugali+Kunde for supper, but fearing the Katch Kids may refuse, I bought half a kg of omena - a delicacy I was sure they would all love.

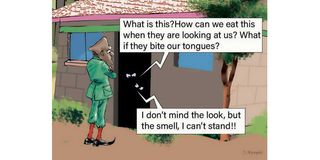

“What is this?” Electina asked as she opened the bowl of omena. “How can we eat this when they are looking at us? What if they bite our tongues?”

“I don’t mind the look, but the smell, I can’t stand it!” exclaimed Honda.

“Enough girls,” I told them. “The quicker we get used to this life in Mwisho wa Lami the better.” I also informed them they will be changing schools from the second term.

“You mean I will not go back to Hill School Kakamega?” asked Honda.

No. You and Sospeter will go to Mwisho wa Lami Primary School. It is a good school, I am the principal,” I assured them.

I also told Electina that we were looking for an affordable secondary school, as we could not afford the private boarding school Fiolina had taken her to.

“Gosh, what about my friends?” What about my friends?”

“You will make new ones,” I told her, adding that I preferred a day school for her.

“Boarding schools are not even good as they are becoming a breeding ground for cults,” I told her. “We need to closely observe you and mold you into an amazing God-fearing woman,”

I dismissed Fiolina’s reservations about my plans, and even told her that if she does not agree with me, the girls should go back to Tocla, their father. In the meantime, Branton had a field day with Omena!