My love for Kiswahili grammar and patience led me into writing

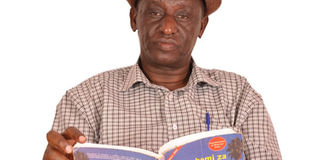

Writer Gichohi Waihiga, who writes books on Kiswahili grammar. PHOTO| BENJAMIN SITUMA

What you need to know:

I wrote several follow-up letters with no response. Just as I was making arrangements to travel to Tanzania to search for the material, I got a surprise reply — not from any of the institutions, but from an individual known as Alfred Bengani.

In his letter, he said he was a low cadre employee in an institution of Kiswahili research in Tanzania and that he had watched helplessly as my letters went unanswered.

He offered to assist me. He sent me his passport photo as I sent him mine. We became pen pals.

It was never in my plans to ever write a book. My first posting after university was at Aga Khan High School in Nairobi.

I taught Kiswahili there for three years and decided to settle down in Nairobi. However, events suddenly took a new turn when I was transferred to Kagumo Teachers Training College in 1984. I felt completely disoriented.

At Kagumo, I was assigned to teach Kiswahili grammar. I noticed the big difference between what I was used to at Aga Khan and what was expected of me at Kagumo.

For a start, my students consisted of mature learners who had taught in secondary schools as untrained teachers for several years; some rising to be head teachers.

They therefore expected a lot more from me. But there was a problem – lack of research and reference materials.

At the time, the most authoritative Kiswahili grammar books were products of foreigners. These included E.O. Ashton’s Swahili Grammar (1944); Edgar Polome’s Swahili Language Handbook (1967); P.M. Wilson’s Simplified Swahili (1970); G.W. Broomfield’s Sarufi ya Kiswahili (1975), among others.

As expected, grammar terminology used by these researchers leaned more towards English. For instance the word ‘sentence’ was referred to as sentenso or fungu la maneno; ‘tense’ was tenso and so on.

To better empower my trainees, I couldn’t wholly depend on these books. So, in March 1985, I wrote a letter to various Kiswahili research institutions in Tanzania asking them to send me lists and cost of their grammar publications. However, one year later, none had bothered to reply.

We became pen pals

I wrote several follow-up letters with no response. Just as I was making arrangements to travel to Tanzania to search for the material, I got a surprise reply — not from any of the institutions, but from an individual known as Alfred Bengani.

In his letter, he said he was a low cadre employee in an institution of Kiswahili research in Tanzania and that he had watched helplessly as my letters went unanswered.

He offered to assist me. He sent me his passport photo as I sent him mine. We became pen pals.

Within a year I had received most publications that I required from Bengani. Now ‘adjective’ was no longer ajektivo but kivumishi; ‘preposition’ was no longer preposito but kihusishi; ‘conjunction’ was no longer kanjungo but kiunganishi, and so on.

Matters had really changed. Sadly, I never met my friend Bengani. In his last communication he said he had left Dar-es-Salaam and was working in a teachers college near Moshi. But my letters there went unanswered. I still hope to meet him one day.

I now approached my teaching with rejuvenated vigour, and by 1989 I had accumulated rich grammar teaching notes.

Using a manual typewriter, I typed the notes, organised them into a manuscript, and presented them to Longhorn Publishers (then Longman Kenya). After evaluation, the publisher made a decision to develop the manuscript into a grammar book.

I was delighted, as I knew that this publication would be a key resource for Kiswahili teachers and students in secondary schools, colleges and universities.

In January 1991, Kiswahili was no longer on offer at Kagumo. I asked TSC to deploy me to Kisii Teachers College, which was granted. Kisii College, proudly known as ‘Kisco,’ gave me another suitable platform to continue with my research.

While at Kisii, I kept following up on the manuscript at Longhorn. I left Kisco in April 1994 to join Kenya Institute of Education.

At KIE I continued teaching Kiswahili through electronic media and participating in curriculum development activities.

Now back in Nairobi, following up on my manuscript at Longhorn was easier. Said Ahmed Mohamed, a well-known Tanzanian Kiswahili scholar, who at the time was teaching Kiswahili in Japan, was the manuscript evaluator and advisor. Since there was no e-mail communication then, the manuscript could only be sent to him through courier. His feedback followed the same channel. Later, Said Ahmed left Japan for Germany, and the script had to be rerouted to Germany.

Finally in 1999, Sarufi Fafanuzi ya Kiswahili was published — ten years after presenting the manuscript to Longhorn. I didn’t regret the wait, as through my interaction with Said Ahmed, I learnt a lot from him. Well, again, I never met Said Ahmed, but I consider him my great teacher.

Coincidentally, Sarufi Fafanuzi ya Kiswahili was published at a time when a new syllabus was about to be launched. The syllabus adopted the syntactical method of noun classification as opposed to morphological method. Reference books that had expounded on this method were scarce, and Sarufi Fafanuzi ya Kiswahili was one of them. For this reason, many authors who developed textbooks for the new syllabus used this book for reference, especially on noun classification.

After the launch of the new syllabus, I presented a proposal to Longhorn Publishers to allow me co-author a secondary school Kiswahili course book series titled Chemchemi za Kiswahili, a title that I had retained in my memory for a long time. When the publisher bought the idea, I partnered with Prof Kyallo Wadi Wamitila of the University of Nairobi.

A lot has happened since. More publications have come along — 24 in number — some individually developed and others co-authored. They include Kurunzi ya Insha Kidato cha 1&2 and Kurunzi ya Insha Kidato cha 3&4 (Spotlight Publishers); Darubini ya Kiswahili (Phoenix Publishers); Kamusi Changanuzi ya Methali (Moran Publishers); Kioo cha KCSE Kiswahili (Spotlight Publishers); Kamusi Fafanuzi ya Misemo na Nahau (Spotlight Publishers); Kiswahili Teule (Moran Publishers); among others.

As I worked on the books, I saw the need to empower foreign English-speaking nationals with basic Kiswahili to enable them communicate with locals. I therefore started a website — simpleswahili.com — which still in its early stages of development, but has been enhanced with animated videos and language games.

So far, people from more than 80 countries have visited the site.

Along the way I have met wonderful people who have added value to my work. They include Simon Sossion (currently CEO, Spotlight Publishers and formerly publishing manager, Longhorn Publishers); F.M. Kagwa, Said Ahmed Mohamed, Professor Kyallo Wadi Wamitila, Njoroge wa Magoko, Hugholin Kimaro, Alfred Bengani, Kithaka wa Mberia, Richard Mgullu, as well as my trainees at Kagumo and Kisii teachers colleges. More publications are on the way.

Finally, Kiswahili is our national treasure. Let’s keep the fire burning.

Mr Waihiga is the Deputy Director at the Education, Standards and Quality Assurance Council, Ministry of Education. [email protected]