Women lead the way in octopus fishing, reaping bumper rewards

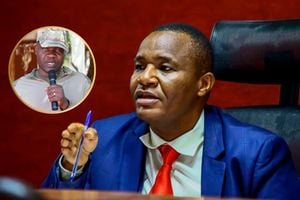

A ranger from Ndo Pate in Lamu County helps women weigh octopus

What you need to know:

- The main economic activity here revolves around the sea.

- There aren’t many opportunities, particularly for women, but the narrative is changing.

Tucked on the Eastern side of Lamu’s biggest island — Pate — is a small, remote village known as Shanga Ishikani. It is one of the 10 villages that make up the Pate Marine Community Conservancy. A walk through the village reveals little infrastructure and activity, a stark contrast to the bustling mainland.

The main economic activity here revolves around the sea. There aren’t many opportunities, particularly for women, but the narrative is changing.

Amina Ahmed, a 40-year-old mother of five, has lived here all her life, taking care of her family and homestead. Like all the women in the village, Amina’s livelihood was for a long time dependent on fishermen, the traditional breadwinners. But today she is claiming that title — she is a fisherwoman.

With just two long wooden spears and a bucket, her equipment is minimal, but sufficient. As we walk towards the ocean, Amina asks locals to join us even as we wait for a boat to arrive. Today is a special day that everyone has been waiting for — it’s the octopus harvesting day.

About 15 minutes into the journey, unusual objects — bouys — stick out of the water, swaying to the rhythm of the ocean. Amina explains that these are boundary markers of a critical and protected zone called Ijamba Idodi in Ndo Pate within the Pate Marine Community Conservancy. Here, fishing is restricted to certain times of the year, like today. So important is this zone that rangers, young men drawn from the community, have been employed to patrol it.

The high tide is receding and we head to the meeting area, where everyone is patiently waiting for the octopus fishing grounds to be opened. The grounds are normally closed off temporarily to allow the octopuses to grow. “It’s our day to open the octopus closure. I am happy because I was chosen by the community to lead them in this venture and given the title ‘Mama Pweza’ — mother octopus,” says Amina.

Amina has earned the name because she has been leading a number of women in octopus fishing to sustain their livelihoods. Octopus is a healthy food that is extremely rich in many nutrients known to support optimal human health, but it also one of the hardest to catch because it is considered the most intelligent of all invertebrates. It has a head and eight arms, each with its own brain.

For years, the residents of Shanga Ishikani had struggled to make ends meet. They relied heavily on this area in Ndo Pate for seafood, but it became degraded, resulting in declining fish populations.

Mr George Maina, the Africa Fisheries Strategy Manager at The Nature Conservancy, an organisation that seeks to safeguard productive marine and freshwater fisheries, says this was a man-made problem, citing destructive fishing practices. “The use of illegal fishing gears is very common. There is also over-fishing of some key species, and this is as a result of weak management and governance of community institutions and other institutions in charge of fisheries”.

The drop in the fish catch took a toll on livelihoods. But in April 2018, the tides started turning when an opportunity arose for locals to go on a benchmarking trip to Madagascar to learn about best fishing practices and the benefits of octopus farming, thanks to The Nature Conservancy and other stakeholders such as the Northern Rangelands Trust (NRT).

Hassan Yusuf, the Coast regional director of NRT, says farming octopuses was a viable option to explore due to their biological and ecological characteristics. “They mature fast, have a short lifespan of between 18-24 months, lay many eggs hence have a high survival rate, and they also have short movements. So you don’t require a big area to establish an octopus closure.”

The community realised that the venture could change their fortunes.

On the trip to Madagascar was Mahmoud Madi, the chairperson of the Pate Marine Community Conservancy, which aims at improving livelihoods through conservation and sustainable use of natural resources. “We asked the octopus farmers in Madagascar what had made them succeed. They said the first thing was that Beach Management Units had come together, and the second thing was women being on the frontline. They have a women’s association, and we replicated this back home. We trained our women and they started leading the way in octopus farming revolution.”

Science was critical in determining the location and size of the octopus closure. In December 2018, the women set aside 115 hectares. Three Beach Management Units came together and developed their own fisheries co-management plans and by-laws. But there was a catch. For this to work, the closures would be out of bounds for four months to allow the octopus to breed. They would open for just seven days for fishing.

However, the idea was met with resistance. And then there was a condition — if the octopus catches were low, the plan would be abandoned. But the women were determined not to give up.

Hassan says: “When they opened the closures for the first time in April 2019 , they got 186 kilogrammes. It was not a good harvest. They immediately convened a meeting to discuss how they would improve. When they opened for the third time, they got 1, 500 kilogrammes.

Residents of Shanga Ishakani in Lamu head to the neighbouring Ndau Pate Island for the seasonal fishing of octopus.

This motivated them to keep going.” Ijamba Idodi became Kenya’s then first and only sustainable octopus fishing project, established and run by women, who were defying the status quo. Each octopus opening season kicks off with a competitive bidding process. The highest bidder gets to buy the entire catch throughout the opening period. The current market price per kilogramme is Sh150, but today, someone has put in a bid for Sh430 per kilogramme.

Octopuses, which like coral and clean water, are mainly fished during the spring tides when the low tide is at its lowest, exposing the reef flats. This makes fishing easier and safer for the women; especially those who cannot swim.

It’s 9am, and the women wade into the water. They look for tell-tale signs of tiny bubbles on the surface to indicate where a well-camouflaged octopus might be hiding between rocks and coral.

Amina suddenly announces that she has spotted a potential hiding place. She tries her luck. “It’s a struggle and not for the faint-hearted as it requires skills,” she explains. Eventually, she manages to get the octopus out of its hiding place. She notices it is missing some arms. “If I left it to die, it would be a loss to me,” she says.

We continue searching under the blazing sun, almost a kilometre away from the shore. Finally, we get one that is not hiding. With its quick and short movements, the octopus tries to get away, but Amina goes after it. It even squirts ink as a defence mechanism to distract her as it normally does to keep predators away. Finally, with a quick jab, Amina wins the chase.

Elated, she removes stones from the suckers on its arms and puts it in her container.

A few minutes later, we find another hiding place. But this one proves hard to get. “It has refused to come out and thus we will leave it here. That’s not my wish, but we can’t break the coral. Our duty is to conserve it,” says Amina.

The fishing expedition comes to an end at around noon and everyone heads back to the shore as the tide comes flowing in. The women meet at a point where the weighing of their harvest happens.

It has been a successful day.

Amina’s catch weighs 4. 27 kilogrammes. From here, the octopuses are put in cooler boxes and transported to Mombasa for export.

Misbahu Awadh, a community fisheries expert, leads the fishermen and women in monitoring the catches. This is a key part of the project, providing important fisheries indicators that are useful for evaluating the closures.

“Initially, we didn’t know there were different species of octopuses. The experts from Madagascar also taught us how to identify the females and the males. Mostly, we catch the Sinea species as it stays in shallow waters.”

They also determine the octopus’ age by counting the suckers on its arms.

The short-term closures of the fishing grounds have proved to be a catalyst for conservation and the best practice in sustainable fishing of the octopus as it alleviates pressure on the ecosystem, allowing the area to regenerate and thrive. The women save some money in a joint bank account. At the end of the year, the savings are split between Pate, Shanga Rubu and Shanga Ishakani Beach Management Units.

The women have used some of their earning from octopus sales to buy two boats. The project has indeed transformed Shanga Ishakani. There are more buildings and electricity. And one building in particular, the pride and joy of the women, is set to change the lives of children The women started building a nursery school, which was completed by Lamu County government, which has also supported the octopus project by buying a boat, freezers, cooler boxes and other fishing accessories.

Octopuses are critical to marine ecosystems as they serve as food to other marine organisms and also feed on others, therefore bringing balance to the ocean. The octopus project in Nado Pate appears to be a working model — it is improving livelihoods, enhancing women empowerment and also conserving marine ecosystems. News of its success is already spreading to communities as far as Kiunga, bordering Somalia, and there is hope of expanding the project along the Kenyan coast.

Additional reporting by Robert Gichira. Watch NTV Wild Talk “Lamu’s Octopus Farm” TONIGHT on NTV at 8.25pm, or on ntvkenya.co.ke