Breaking News: At least 10 feared to have drowned in Makueni river

Remove fallopian tubes to prevent ovarian cancer, scientists advise

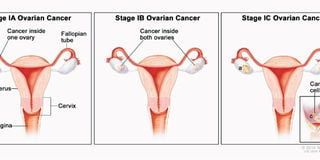

Early detection of ovarian cancer is key to effective management and treatment of the terminal disease. FILE PHOTO | NMG

What you need to know:

- The scientific process of removing a fallopian tube is called Opportunistic Salpingectomy.

- Backing a recommendation from cancer gynaecologists that came about a decade ago, the new endorsement advises women undergoing non-cancerous surgeries such as tubal ligation, cysts removal, endometriosis and hysterectomy to consider doing away with their fallopian tubes.

Women at risk of ovarian cancers may be required to remove their fallopian tubes as a way of reducing the threat of acquiring the chronic illness.

These are tubes in the female reproductive organ that act as a conduit for a woman’s eggs from the ovaries to the uterus. While it is not clear what causes ovarian cancer, scientists suspect that it starts from the fallopian tube.

The scientific process of removing a fallopian tube is called Opportunistic Salpingectomy.

Backing a recommendation from cancer gynaecologists that came about a decade ago, the new endorsement advises women undergoing non-cancerous surgeries such as tubal ligation, cysts removal, endometriosis and hysterectomy to consider doing away with their fallopian tubes.

The scientists from the Ovarian Cancer Research Alliance (OCRA) in the United States said the excision is an easier way of eliminating ovarian related cancers. “Fallopian tube is the origin of most high-grade serous cancers. The tube’s removal has been shown to dramatically reduce risk for a later ovarian cancer diagnosis,” said a statement from OCRA.

Unlike other forms of cancer that can be managed if detected early enough, the tale of ovarian cancer treatment is quite unpredictable and doctors say early detection may not be a magic bullet.

“In many cases, the stage at diagnosis may not significantly impact whether a patient dies from the disease. Detecting ovarian cancer earlier in the course of its disease progression — which could be at an earlier stage — may not prevent a woman from dying,” said the OCRA scientists.

When the Society of Gynaecologic Oncologists (SGO) first made the call to women to consider removing their fallopian tubes, it was a strange way to prevent cancer risk.

The scientists were clear that women who had given birth and were not interested in more children were eligible for the procedure. This, they said, would be a better option to replace tubal ligation.

“I would do that after giving birth, even just one child, that is already a blessing and I’d rather save my life,” said Gloria Grace from Nairobi.

Winfred Aura said she would not have a second thought when such an option is presented to her, whether her kin agree to it or not. “I would do it because it is about my health. It’s like being told that my leg needs to be amputated to prevent a form of cancer or disease from spreading. Same case as donating a body organ like the kidney to save my sibling. Same way as these scenarios, I will still save my life if that is the only option,” she said.

In addition to being a difficult type of cancer to manage, a statement from the scientists shows that its screening is equally challenging and often not easily detected. They paint a grim picture saying that a viable solution in the current world for cancer screening could possibly come through in about 10, or even 20 years to come.

“Not only do current screening methods not save lives in the general population, but they can also actually cause harm. Screening can lead to false positive tests, resulting in a cascade of anxiety-provoking investigations and sometimes unnecessary surgeries that can pose emotional and physical risks to patients, not to mention financial hardship,” said the OCRA scientists.