From barren to bountiful: How Kisilu thrives in a changing climate

Community leader and farmer, Kyavando Cooperative (Kitui), Kisilu Muasya, during the Earthwise Summit at KWS Club House in Nairobi on Thursday.

What you need to know:

- For the next seven years, we filmed our community’s changing seasons, struggles, small victories, and growing resilience.

- That journey led to the creation of ‘Thank You for the Rain’, a documentary that has since been screened in cities worldwide.

“If you have never set foot in Kitui County, you would likely picture a barren land—scorched earth, cracked soil and skies that hold back rain season after season. And you wouldn’t be entirely wrong. Mutomo sub-county, where I was born and raised, is dry. The rains are erratic, and many lands are unutilised. On the surface, it seems like the land is forever waiting, forever wanting.

But that’s just one side of the story. The other side is more challenging to see, but it’s there. Through years of learning to adapt to the shifting climate, many community members have found ways to prosper against the odds. Where others see drought, we see innovation. Where others see scarcity, we find new ways to sustain ourselves.

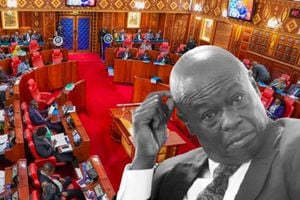

Delegates following proceedings during the Earthwise Summit ‘24 at KWS Club House in Nairobi on Thursday.

I remember walking to the farm as a child, trailing behind my parents as we went to work on the farm. Along the way, we would stop to pick wild fruits—berries, passion fruits and mangoes. Also, there were water springs. My parents planted maize, millet and sorghum for subsistence, never more, because they believed this land could only provide so much. It was what they had been taught. When I started my family, I naturally followed in their footsteps, becoming a farmer like them. But by then, something had shifted. The wild, indigenous fruits and the springs were gone. And the farming methods I had borrowed from my parents? They were failing me. The rains came later, if at all. The soil seemed tired, unwilling to give.

I was about 25 years old when I realised things weren’t the same. That’s when I started asking questions. What had changed? Why wasn’t the land responding as it once had? Month after month, I watched some villagers pack up and leave, hoping for a better life elsewhere. But I had a family to feed, roots in this place. I had two children then, but I am now a father of nine. I couldn’t leave. I needed this land to work for me, and the desperation kept me searching for answers.

When I realised the old ways were no longer working, I asked other farmers for answers. Many of them were just as frustrated as I was. They told me the same thing: farming wasn’t yielding what it once did. That’s when I sought help and was introduced to an expert who had been working with farmers facing similar challenges.

He brought together a group of about 30 farmers from the area and for the next year and a half, we met regularly for training sessions. It was during these sessions that I began to understand what had changed. We learned about climate change—not just as a distant, abstract idea but as something directly affecting our land. The trainer explained how careless farming practices, deforestation and poor conservation had played a role in the shifting climate patterns.

But what struck me most was how deliberate and patient our trainer was. He didn’t just dump solutions on us and walk away. He was clever and methodical. He understood that for real change to happen, we needed to see the value in it ourselves. So he didn’t start by lecturing us about climate change or hammering us with facts. Instead, he introduced ideas in ways that made sense to us. He talked about the importance of seed selection, when and what to plant, and the timing of the rains.

And when it came to tree planting—something we had ignored mainly—he didn’t simply tell us to plant trees. Instead, he framed it in ways we could relate to growing fruit trees for food or wood for building and firewood. Trees as windbreakers to protect crops. It all made sense once we understood how we could benefit. But at the heart of it all, whether for fruits, firewood, or wind protection, it still came down to one simple thing—planting trees. We began to see that pawpaws and fodder trees weren’t just part of the landscape; they were part of the solution.

We had seen livestock die before, but that started to change when we learned how to feed them properly and introduced fodder into their diet. Then, I began to truly understand the value of changing how we farm. We shifted from pure crop farming to farm forestry, mixing crops and trees. If you visit my farm today, you’ll see that transformation first-hand. I grow drought-resistant crops like sorghum and millet alongside pawpaws, cassava, and mangoes. And I don’t just grow enough to feed my family—I sell to others, ensuring food security for myself and the community. But it’s not just about having enough food—it’s about doing it correctly. We make our organic sprays and use ecological farming practices free from harmful chemicals. It’s better for the soil, better for the crops, and better for the people who eat them.

I have about 25 acres under cultivation. I have planted grass specifically for my animals on another piece of land. Alongside crops, I keep beehives for honey, hens for eggs and goats and cows for milk and meat.

In 2011, two filmmakers came to our village, looking for farmers with firsthand experience with the negative impacts of climate change. At the time, I was already documenting what was happening—writing down what I saw, recording the changes I had witnessed over the years and the impact on our land, crops and animals. They were looking for someone who could tell the story of climate change from the ground up, and I was selected.

They stayed with me for a month, learning from my experience and seeing the reality of what we were dealing with here in Mutomo. They trained me to use a camera, showing me how to capture what I was already documenting in words, now through the lens of film.

For the next seven years, we filmed our community’s changing seasons, struggles, small victories, and growing resilience. That journey led to the creation of Thank You for the Rain, a documentary that has since been screened in cities worldwide. What started as a simple act of recording my own experiences has opened doors I never imagined—opportunities to travel from Oslo to Munich, Paris to Copenhagen and Stockholm and be part of global climate conversations like the Conference of Parties (COP). But more than the travel, it’s about giving a voice to the farmers, the men and women who are on the frontlines of climate change every day, adapting, surviving, and finding new ways to thrive.

When I first heard the term “climate change,” I had no idea what it meant. In my mother tongue, we call it thano—drought—because that’s what we associate it with. After the training sessions, we became local “scientists” and started researching crops that would thrive in this changing environment. We shifted our thinking—from planting what we wanted to planting what the land could sustain and what would bring us income. It became a matter of survival but also of opportunity.

For example, we have always eaten rice, but it doesn’t grow well here. So why not focus on drought-resistant crops with market demand—like sorghum, millet and cassava? It’s no longer about just subsistence farming; it’s about building a sustainable livelihood. And it’s working. So much so that we’ve created a resource centre where farmers meet every Thursday. We also hold field days and invite experts to join us on the ground, sharing knowledge directly in the fields where it matters most.

Our centre has also become a learning hub—not just for farmers, but for the next generation. We invite students from nearby primary and secondary schools to learn about climate change and how to adapt. We want to ensure that adaptation doesn’t stop with us when we grow old. These children are the ones who will carry forward the fight against climate change, and we’re making sure they’re equipped with the proper knowledge.

I see this change in my own family. Three of my children study agriculture-related courses at university, inspired by what they’ve seen and learned from our efforts. One of my daughters, still in secondary school, is already a climate change activist. She’s making a film about building resilience in the face of climate change.

It amazes me how far we’ve come—from when I didn’t even know what climate change was to now having a family that understands its impact and is actively working to combat it.

What’s even more interesting is that in many ways, things have changed for the better. Our farming is more profitable, and the community is stronger and more informed. This journey started with learning how to adapt, but now it’s about thriving in a constantly changing world.

Beyond the income I make from the farm, I have found other ways to support my family and share what I have learned. I now earn money facilitating talks on climate change adaptation, sharing our experiences with farmers and communities in different parts of the country—and even worldwide.

As farmers, we must continuously learn how to adapt. The rains may be unpredictable, but that doesn’t mean we are powerless. One of our most important lessons is how to make the most of the little drops of water that fall on our lands. Whether through water conservation techniques, planting drought-resistant crops, or farm forestry.

I am a full-time farmer. It is through farming that I am alive.”