Cleft lip repair: Healing a child’s smile and a mother’s heart

Faith Mbula after undergoing a cleft palate surgery on May 23 at Gertrudes Children's Hospital in Muthaiga.

What you need to know:

- In the early weeks of pregnancy, typically around five weeks of pregnancy, the face starts to form from different sides and the parts come and fuse.

- In cleft lip and palate, there is a lack of fusion or meeting of the parts of either the lip or the palate, resulting in a gap.

Alot has changed since Esther Kalekye, 29, became a mother six years ago. On a particular day in July 2018, the day she delivered her firstborn daughter, the word “cleft lip” held the weight of a thousand unspoken anxieties. She remembers crying and bombarding healthcare professionals with questions, desperately seeking clarity about her medical condition.

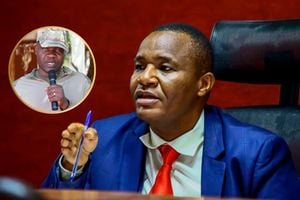

Esther Kalekye, whose daughter was born with a cleft lip and palate.

Fast forward to today. Esther sits confidently on a plush armchair in a doctor's office, awaiting her daughter’s review after a recent surgery. When she talks about cleft lip, the mother of two does it with the practised ease of a seasoned physician, her sentences peppered with terms like “nasal reconstruction” and “speech therapy.”

Yet, a lot goes back to the day she had her daughter as it was also the first time that she heard about cleft lip and palate. Despite being a common birth deformity with a global incidence of one in every 1,000 live births, Esther knew nothing about clefts.

“I had never met or even seen anyone who had one. When I returned to my village — Kyumbi in Machakos County — after a two-week hospital stay, I realised that it wasn’t just me who didn’t know about it. The people here didn't know about it either. Even as I was desperately trying to understand my daughter’s condition, I had to explain it to others ,” she says, a touch of sadness tinging her voice.

Dr Tom Osundwa, a consultant oral and maxillofacial surgeon and a senior lecturer at the University of Nairobi, has been involved in paediatric surgeries and carried out dozens of cleft lip and palate operations for years.

“In the early weeks of pregnancy, typically around five weeks of pregnancy, the face starts to form from different sides and the parts come and fuse. In cleft lip and palate, there is a lack of fusion or meeting of the parts of either the lip or the palate, resulting in a gap,” he explains.

According to the Centre for Diseases and Prevention, the severity can vary, with some babies having a small notch in the lip while others may have a wider separation.

“This gives a facial appearance that is grotesque and normally has implications on function. So, because of that, smiling, speech and chewing may be affected. Sometimes, it can also impact hearing. And basically, the impact is beyond that because the face is an important corridor to many things,” offers the surgeon.

Even as Esther continued to figure it out, not knowing what it would mean for her baby, the more pressing issue was that the baby couldn’t latch properly.

“It was a lot to deal with. On one hand I was trying to wrap my head around this whole cleft lip and palate thing—a phrase that kept bouncing around in my head. On the other hand, all I could hear was my baby’s cries. She was getting frustrated and struggling to feed. Then, to top it all off, back in the village, people couldn't help but ask questions. “Why isn’t the baby gaining weight?” They would ask, their words well-meaning but landing a little harsh on my already stressed ears. Word went out and after three months, which seemed like a lifetime to Esther as she describes it, her baby was booked in for a cleft lip surgery. “After six months, we went to the hospital again to correct her palate. I knew that the sleepless nights were behind us,” she offers.

At the hospital, doctors recommended that her baby only consumes fluids. “It was a big financial burden to provide her with the required diet because I don’t have a stable source of income,” she says.

Dr Osundwa says there is a correlation between cleft lip and malnutrition. “What we see in some patients is iron, zinc , folic acid, vitamin B6, B12 and B3 deficiencies, and they are all associated with cleft lips. This is especially reflected in the high prevalence of clefting in the lower socioeconomic status.”

Over time, the baby developed further complications attributed to poor management of the wounds and even after gaining the required weight, doctors needed to observe her before taking her in for another surgery.

“When her case was brought to our attention, we discovered that the initial surgery was not properly done and because of the wound that had formed, we had to book her for another operation.

However, we had to first monitor her weight and haemoglobin to ensure that it was up to par. This is a journey that took about two years. Ideally, All this should have happened before she turned one year old, but we are doing it when she is almost turning seven years old,” says Joseph Kariuki, senior programme manager for Eastern and Southern Africa at Smile Train, an international children’s charity.

In Kenya, for instance, Mr Kariuki says the organisation conducts at least 800 surgeries every year.

“And I think it could be more, but there are challenges. Because we currently do not have enough medical personnel to be able to provide this care. And more specifically the cleft surgeons. And when you look at cleft care, there is a whole ecosystem. This includes nutrition, speech therapy, orthodontics, psychosocial support, oral health, (ENT) Ear, Nose and Throat and audiology. So, there is lack of professionals and the issue of funding. This has created a backlog and we are trying to address it through training and capacity building,” he says. Through partnerships with different hospitals, Smile Train supports patients seeking treatment for cleft lip and palate. While the definitive cause for cleft lip and palate remains largely unknown, Dr Osundwa offers that the formation is a mixture of genetic and environmental factors that sometimes involve the mother. “One of the factors is deficiencies and this can be a lack of vitamins like B6, and B12, iron, and micronutrient deficiencies like zinc,” says the microfacial surgeon.

Ideally, the management of these cases, Dr Osundwa notes, should start during prenatal clinics, where an ultrasound can easily pick out children with clefts.

For now, Esther’s daughter is learning to talk through the help of a speech therapist and with the reassurances from doctors, soon she will lead a normal life.