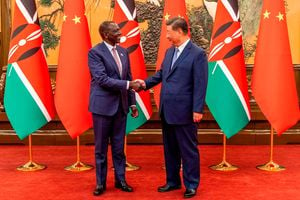

President William Ruto and President Xi Jinping of China during the high-level meeting on the Belt and Road Initiative in Beijing.

Extension of the Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) line from Naivasha to Malaba topped President William Ruto’s agenda in his China visit last week, underlining his government’s commitment to see Kenya’s largest infrastructural project touch the Ugandan border.

And as Africa walked from the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (Focac) with a $50 billion funding pledge, President Ruto hoped to get a $5.3 (Sh685) billion share to fund construction of the line to Malaba, a project that is set to revive questions on its viability after the current line between Mombasa and Naivasha- still largely unviable- left unanswered questions.

President Ruto on Tuesday indicated that he met the company that constructed the Mombasa-Naivasha SGR to discuss the SGR extension.

“Held talks with the leadership of the China Communications Construction Company led by Chairman Wang Tongzhou in Beijing, China. Discussed various projects such as the Rironi-Mau Summit-Malaba dual carriageway, Galana-Kulalu Irrigation Project, Bomas International Conference Centre and the expansion of the SGR into the region,” he announced on his X account on Tuesday last week.

In May then Transport Cabinet Secretary (CS) Kipchumba Murkomen projected that the extension would cost $5.3 billion- a Sh200 billion increase from the $3.68 billion estimated cost in 2019- as he noted that the government hoped to raise the funds “through PPP (Public-Private Partnership) or loans.”

The government is, however, pursuing extension of the SGR line even as the current project continues to struggle with heavy costs, depreciating assets, and a web of secrecy over the manner and costs at which it was procured, even as taxpayers are slapped with hefty interest payments every year.

Questions regarding procurement of the SGR began as soon as its construction started in November 2013 though the government has been adamant to disclose contract details.

In December 2018, President Uhuru Kenyatta promised to release the SGR contract in a live TV interview but never did.

President Ruto made a similar promise before his 2022 election. But Mr Murkomen only published one of the loan agreements on the project last year.

The questions started in 2013 when Parliament set out to investigate issues relating to the SGR cost and concerns around tendering process before China Road and Bridge (CRBC)- a Chinese state-owned firm- was awarded the tender.

A 2014 Public Investments Committee (PIC) report shows that during the fact-finding mission, MPs’ attempt to invite CRBC to shed light regarding issues raised about the project was met with a fiery warning from China.

“The firm failed to honor the committee’s invitation and summons and instead the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Kenya) after receiving a note verbale from the embassy of the People’s republic of China wrote to the committee indicating that CRBC is a state-owned corporation and should not therefore be summoned by the committee,” the report notes.

It notes that in a February 5, 2014 letter to then National Assembly Speaker Justin Muturi after Parliament summoned CRBC General Manager Li Qiang, Foreign Affairs PS Karanja Kibicho reverted with a warning.

“It is the opinion of this Ministry that summoning and questioning CRBC in relation on this matter would be tantamount to summoning the Government of China since the corporation is fully owned and acting on behalf of the Chinese Government, such a measure is likely to have serious and irrevocable negative consequences to Kenya's national interests and relations with China,” Mr Kibicho wrote.

CRBC never appeared before the committee but continued with construction.

Transport ministers who committed Kenya to CRBC for construction of the SGR, Mr Amos Kimunya and Mr Chirau Mwakwere, also refused to provide information and answer questions regarding the SGR project. The committee recommended the prosecution of Mr Kimunya.

It was established during the PIC investigation that at the time CRBC was procured to construct the SGR, the World Bank had debarred it for fraudulent practices while undertaking a road project in the Philippines.

Mr Mwakwere indicated that he committed Kenya to CRBC for the SGR project even as he knew that the company had been backlisted by the World Bank because the Philippines issue was an isolated case since the company had not had integrity issues in Kenya.

Under the contract, CRBC was handed deals on a silver platter, where it did the feasibility study, determined cost of the project, identified the financier and was directly handed the contract.

“This raises issues of conflict of interest and lack of due diligence as well as questions as to whether Kenyans will get value for money on the project due to lack of competition in the procurement process,” PIC posed.

Then Kenya Railways’ acting MD, Alfred Matheka, told the committee that the corporation’s attempt to get an independent firm to conduct feasibility study on the SGR after CRBC presented its was stopped by Mr Kimunya who was Transport Minister at the time, to pave way for the contract on a Government-to-Government (G-to-G) basis.

The committee ruled Mr Kimunya’s action as interference in the procurement process.

“The procuring entity (Kenya Railways) was sidelined to the periphery during the procurement of CRBC to undertake the feasibility study and preliminary designs,” the committee stated.

The Public Procurement Oversight Authority (now defunct), told the committee that it had advised Kenya Railways against handing CRBC the contract directly, but Kenya Railways without providing documents, claimed the contract was a G-to-G.

At the time, Attorney-General Githu Muigai faulted the G-to-G procurement for SGR as one that lacked competition, transparency and accountability, though his advise never changed the course of things.

“I would favour a construction that holds G-to-G agreements as not being methods of procurement, but merely bases that could support procurement activities subsequently,” Prof Muigai said.

After the presentation of feasibility study and documents detailing how the project would cost, Kenya Railways management, led by then MD Nduva Muli, went to conduct due diligence in China and the Chinese Embassy in Kenya, ending up awarding CRBC the contract.

The committee learnt that those were the circumstances under which the contract for the construction of SGR was awarded, a project that has now been part of Kenya for a decade- seven years of which it has been in operation- but which continues to struggle, even as assets wear out and render its viability even more difficult.

The cabinet approved the SGR project on August 3, 2012 and at the time it was expected that it would run from Mombasa to Malaba, with a line linking to Kisumu.

In the latest publicly available Kenya Railways report, the corporation admitted that the loan borrowed for SGR construction was one of its major risks, noting that the project was unviable.

“The ability to repay the loan was pegged on performance of both freight and passenger business streams. This has not been sufficient, leading to defaults which come with penalties,” the corporation stated.

At the time, the loan had accrued Sh34 billion principal payments and Sh21 billion interest, but its inability to pay had seen it slapped with a Sh644 million penalty by the Exim Bank of China. The burden was Sh56 billion.

“In the circumstances, the corporation continues to be exposed financially due to non-settlement of the loan obligation,” Auditor-General Nancy Gathungu said after the penalty was imposed.

By June 2021, the Exim Bank loan was Sh569 billion and had accrued Sh50.9 billion payments.

The SGR had by end of 2021 generated Sh47 billion in revenues since starting operations in 2017 and had not broken even, meaning that Kenya Railways spent more money to operate it than it actually generated.

According to the latest national statistics, SGR ferried 18 percent of the 35.9 million tonnes of cargo that passed through Kenya last year.

“The volume of cargo transported via SGR increased from 6,09 thousand tonnes in 2022 to 6,533 thousand tonnes in 2023,” Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) said in the 2024 Economic Survey.

Businessman Jimi Wanjigi, who has publicly stated that he conceived the project as a PPP initiative that would cost a maximum Sh60 billion from Mombasa to Malaba, says the government’s planned extension of the SGR to Malaba will only serve to add more burden to taxpayers, since the project was founded on the wrong model due to the high costs.

“If 70 percent of the volume of goods and passengers is to Nairobi and it has not been viable this 30 percent West of Kenya and Uganda is a no brainer. Its dead on arrival,” he says.

Mr Wanjigi says the viability of SGR would have been based on cost of constructing the line, which would then make transport of goods through it cheap for businesses to buy into the idea.

“We had a cost from Mombasa to Malaba that did not exceed Sh60 billion and we had primarily looked at a feasibility study that told us that goods are the most profitable avenue and that there were about seven main products that are moved between Mombasa and Malaba and that the movement of those products at a reasonable price would have given us a return on that investment between seven to eight years,” he told Nation.

Even as the government pursues the extension to Malaba, details regarding the project and its procurement are not public and Kenya Railways has not issued a tender to that effect.

Transport CS Davis Chirchir and Kenya Railways MD Philip Mainga last week did not respond to questions regarding how Kenya Railways proposes to undertake the extension, whether there exists a feasibility study and a breakdown of the $5.3 billion cost that Mr Murkomen indicated in May.

In WhatsApp and SMS messages to the officials, the Nation also sought information regarding the Mombasa-Naivasha SGR line, particularly money spent on loan payments by end ofJune2024, contract for the project and its financial performance.

Kenya Railways in the year to June 2021 estimated that SGR assets had depreciated by Sh19.7 billion. The depreciation of SGR assets accounted for 98.3 percent of the depreciation of all Kenya Railways assets at the time.

The SGR track depreciation, for instance, was Sh5.3 billion and the corporation estimated that it would only be useful for 60 years. Kenya Railways listed depreciation of the assets by hundreds of millions of shillings, including bridges, culverts, fence, signaling and telecommunication systems, station yards and rolling stocks.

Since the SGR project started, the Auditor-General has been raising queries on its procurement process and operations and has questioned the spending of billions of shillings.

Until June 2022, the latest available public audit for the corporation, Kenya Railways had not provided a list of Kenyans it claimed to have paid Sh1 billion as land compensation during construction of the SGR.

Former Treasury CS Henry Rotich told a parliamentary committee that Sh8 billion had been budgeted to buy 2,253 hectares of land for the railway corridor.

Auditor-General Nancy Gathungu also notes that Kenya Railways has never recovered a Sh3.3 billion advance payment it made to CRBC in June 2010 “for which the terms and conditions of the advance payment were not provided for audit review.”

Ms Gathungu has also been raising queries of discrepancies in revenues reported by Kenya Railways from SGR operations, and in the year to June 2021 noted that while the corporation reported receiving Sh12 billion freight revenue from the Kenya Ports Authority (KPA), the latter reported that it paid Kenya Railways Sh14.3 billion.

Mr Bernard Muchere, a forensic auditor, says that his investigations established that the SGR failed laid down tests to make it a public project, and loans procured for its construction cannot be termed public debt.

Mr Muchere’s argument is that while the constitution requires that all borrowed funds be deposited at the consolidated fund, under the SGR, none of the loans came through, but were instead reported to have been paid directly to CRBC in China, by the Exim Bank of China.

“The conceptualization of the SGR project failed to meet the criteria for establishing a Kenyan public project, whereby there is no evidence showing whether the KRC’s management conceptualized the SGR project and whether the Kenyan public approved the SGR project through public participation as provided under Article 201(a) of the Constitution of Kenya 2010,” he says.