There is no crisis; it’s just a turning point

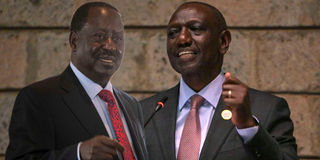

Opposition leader Raila Odinga (left) and President William Ruto.

The anti-government protests by the Azimio la Umoja Coalition Party, and subsequent agreement by the State to convene ‘talks’ with the opposition, have led to reflections on what happened in 2008 following the disputed December 2007 presidential election result.

The dispute led to a violent conflict that almost transformed into a full civil war and divided the country into two equal blocs.

The protests are not the result of a political crisis similar to the intense difficulties that the country experienced in early 2008.

The present challenges, simply put, centre on grievances of exclusion of political elites from power rather than institutional failure, and capture and manipulation of institutions by powerful ethnic elites. The differences are many – but there are similarities too.

The 2008 political crisis

The 2008 political crisis resulted from blatant rigging of the presidential election. The two main parties in the dispute, the government and the Party of National Unity (PNU) of the then President Mwai Kibaki; and the main opposition party, Orange Democratic Party (ODM) under Raila Odinga, accused each other of manipulating the election.

ODM accused the government and PNU of conniving with the electoral commission to declare President Kibaki as the winner using false results.

On the other hand, PNU blamed ODM of rigging elections in its strongholds and cited unprecedented and questionable high voter turnouts as the evidence.

But unprecedented and doubtful high voter turnout was evident in the PNU areas too. Analysis of presidential results later, however, showed that it was PNU that unashamedly and stealthily manipulated results in constituencies that were late in forwarding their results to the national tallying centre.

To be fair to the then Chair of the electoral commission, Samuel Kivuitu, it is the ‘deep state’ of the time that rigged the results.

The commission did not have any knowledge of how the deep state commanded the manipulation of results of many constituencies that were among the last to bring the results at the tallying centre.

The chair was right in publicly stating that the results that had not arrived from even nearby constituencies were being falsified.

The crisis led to the intervention of an international mediation team under the former UN Secretary-General, the late Kofi Annan.

The team established the Independent Review Commission chaired by South African Judge Johann Krieglern to inquire into all aspects of the 2007 elections. Unsurprisingly, the Kriegler commission concluded that all parties participated in electoral malpractices so much that it was not necessary to discuss who won or lost.

The violence that engulfed the country – whether organised or spontaneous – arose from this dispute over results and some evidence that the ODM candidate, Raila Odinga, had won but was denied victory.

Voters could clearly see that some of the constituency results announced at the tallying centre were different from what people were collating using party agents or election observers. This was a genuine grievance.

The violence spread fast also because the opposition did not have confidence with the Judiciary. President Kibaki had staffed the Judiciary with judges he had appointed on his own.

The electoral commission members also had been appointed by the President without consulting other political parties. This was contrary to the late 1990s agreement that commissioners would be appointed through consultations.

The opposition was right that the electoral process clearly tilted in favour of the government.

The fact that President Kibaki had presided over great economic recovery and unprecedented poverty reduction, service delivery and improved infrastructure did not prevent the people from getting into violence. There was genuine grievance – stealing of election.

The 2023 challenges are nothing compared to the past

The 2023 political difficulties are nothing to compare with 2008. It will not sound right for some if we observe that the Supreme Court heard the electoral dispute and upheld the results of the August 2022 elections.

This is a court established under Kenya’s post-2008 Constitution to give confidence to parties to go to the court for determination of presidential election disputes, among others. It was established in response to past experiences where incumbents had their way on matters petitions.

At the Supreme Court, the parties presented evidence to back their argument. Azimio argued that the presidential election result was falsified by use of technology.

The commission presented evidence to show that rigging could not happen even by use of technology. The United Democratic Alliance (UDA) and Kenya Kwanza parties, whose candidate President William Ruto won the election, presented evidence to show that their victory was genuine.

A sample of polling station results were verified and it was confirmed that the results on the digital portal were not different from the hard copy results.

Moreover, many people have questioned how the Azimio presidential candidate would lose an election when the government, incumbent President Uhuru Kenyatta, and many of Kenya’s major capitalists, the billionaires, backed him.

They argue that Azimio had the government, money, power, and super elites that should have made it possible and easy to win. But many also forget that UDA and Kenya Kwanza parties had an innovative narrative on how to uplift the lives of the lumpen, the underdogs or the hustlers.

The narrative of how the ordinary and the powerless would be powerful and how the party would improve their wellbeing completely eroded the layers of ethnic basis of mobilisation that past campaigns depended on.

The hustler narrative resonated with the voters fast. Class divisions became the new basis of organising politics. This was lost to many people. What we have today are not major political difficulties and challenges.

These anti-government protests are just an expression of grievances that are common among elites immediately after election. Those who win get everything and losers lose every thing – this is the basis of antagonism.

Other than the demand to address the cost of living, and reconstitution of the electoral commission, the grievances are incoherent and scattered all over.

But even on the issue of cost of living, the opposition has not tabled alternative policy recommendations to demand that the government implement.

It is true that the cost of living is an issue of concern but an opposition party’s major responsibility is to bring out credible proposals that the public would support if they compare with what the government is presenting. This has not happened.

Kenya is at a turning point

Even with this understanding – that only the question of cost of living is a real concern and that the political grievances are incoherent – both the government and the opposition have agreed to a mediated ‘talks’. But if we go by past experience, the discussions will focus more on ‘inclusion’ into power arrangements under any means.

The discussion will focus on how the opposition political elites get included in power or be presented with eating troughs. This has been a practise from the 1990s – election losers would always find way into new power arrangements.

The only difference today is that the 2010 Constitution prevents both the winners and the losers from presenting the government troughs as a gift to anyone.

If the talks end up with the government addressing cost of living and reconstitution of the electoral commission, and nothing for the opposition political elites as individuals, then practise of politics in Kenya will change.

It will be clear that post-election protests and talks cannot deliver to individual political elites. There is a better country if the focus is on strengthening institutions and respect for the Constitution.

But our political elites cannot stay in the wild for long even though this is what is required to break with the past. How the talks will be concluded matters – they present a turning point in our politics.

But will this happen, or the elites will continue to get something for themselves only?

- Prof Kanyinga is based at the Institute for Development Studies (IDS), University of Nairobi, [email protected], @karutikk.