There goes a truly good leader

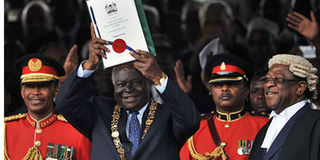

President Mwai Kibaki lifts Kenya's constitution after it was promulgated at Uhuru Park in Nairobi on August 27, 2010.

What you need to know:

- Kibaki was a massively gifted economic policy wonk and capable manager of the economy.

- By the time he was becoming President in 2002, economic management to Mr Kibaki was instinctive.

He nearly made us rich. Between 2002, when he took office, and 2007, when the country caught fire, owning a small business could make you real money. By giving access to mid-level colleges to children from poor families, there was income trickling into that strata. It meant those with money could keep more of it rather than spend it supporting the circles around them.

He opened our eyes to the possibilities of development and economic independence. Everything about his economic play — streamlining tax collection, investing in education, developing infrastructure and deft engagement with the Chinese — was, by our standards, a class act.

Funny enough, I never met President Mwai Kibaki, even during those years when I used to hang around opposition politicians in Parliament. But I came to follow his political career keenly and to speak to many people who worked closely with him, or often saw him at the club or tried to gravitate towards his circle, assuming that such a thing actually did exist. I also researched his history and read a lot of material about his journey from Karima Primary School, through Mang’u and Makerere to the London School of Economics.

Ever the character around whom there was always a bit of drama, his father didn’t particularly want him to go to school: When asked to nominate one of his children to attend school, the old man picked the one who was least useful on the farm. But he did pick a clever one, for sure.

Kibaki was a massively gifted economic policy wonk and capable manager of the economy. He was involved in structuring the post-Independence economy virtually from the get-go. He was an assistant minister for Finance and headed the Economic Planning Commission from 1963, took over the Commerce ministry as minister in 1966 and then the Treasury (as minister for Finance and Economic Planning) in 1969 to 1983, when then President Daniel arap Moi took the economy away from him and gave it to Arthur Magugu.

By the time he was becoming President in 2002, economic management to Mr Kibaki was instinctive. It’s what he had done most of his life; he was a really smart and well-read guy and was trained in economic policy at the LSE. And he had the typical bean counter’s respect for money; many are the journalists who will remember how, during the campaigns, he would retreat to his Range Rover to enjoy a packed lunch and leave it to Mr Njenga Karume or some other person to feed the horde of hungry reporters covering their rallies.

What do I think of Mr Kibaki? I think he loved his wife. In his own undemonstrative way, Lucy was special to him in a way that wives are not to the average husband. To him, she was home. He was not a particularly exceptional husband, he wasn’t the earliest to get home, maybe not even the most faithful in Africa.

But she wasn’t an easy wife either, born into privilege which continued after marriage, explosive in temperament and used to boxing the ears of those around her, possibly his included. He took his punishment like a man, stood by her and — eventually — obeyed her even when her demands included a dose of public humiliation, such as calling a press conference to deny another woman.

Emotionally, from what I gather, he was a frighteningly unavailable person. A natural born loner, content to sit alone with his thoughts and enjoy his beer, the company of others was quite likely forced on him by the demands of public life. As a politician, he travelled light. As a gentleman of impeccable manners, his frequent public insults notwithstanding, if Kibaki was ever brutal, it was likely not in the things he did or said; it was in the things he didn’t feel or didn’t show he felt. And nothing drives those close and dear up a wall as a rock of a person who responds to nothing.

Some of us are called to be preachers, others blacksmiths or teachers. People like Kibaki were meant to be presidents; they come with weaknesses and talents, which makes them peculiarly gifted for that responsibility. Many will say he was too soft and didn’t sack as many people as he should have and could have done more political hatchet work.

Well, many were the errant blue-eyed boys who found themselves neatly tucked under the bus and the acolytes who will be first to admit that once the boss was done with you, even if you were determined to cling on, the wintry distance which opened up made life a living hell.

Poor health denied the country the full benefits of Kibaki’s talents. He was also unlucky that in the moments when he was indisposed, some of his most trusted lieutenants did not quite rise to the lofty heights of duty and debased themselves with corruption and the mismanagement of coalition politics.

He could also have been more generous in his treatment of his political allies, especially the Liberal Democratic Party, and kept his word to Mr Raila Odinga.

When all is said and done, and as African presidents go, however, Kibaki is among the good ones: A truly great leader.