A strangely anti-politics president

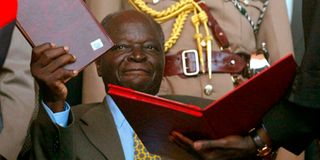

The then president-elect, Mwai Kibaki, holds a Bible as he sworn in as Kenya's third president at Nairobi's Uhuru Park on December 30, 2002.

What you need to know:

- Three months could pass before what President Kibaki had done or said was a lead item on TV or in the newspapers.

- He generated a strong democratic smell in the Kenyan air—despite the occasional takedown of the media.

I came to work with Nation Media Group in Nairobi in January 2003, a few weeks after Mwai Kibaki had been sworn in as President. He was an oddity in the East Africa Community of that period; an opposition politician who had come to power at the largest democratic coalition (the National Rainbow Coalition, Narc) ever assembled on this fair continent outside South Africa.

But more was yet to come.

NMG stuck me in an apartment in Chester House, the old haunt of Nairobi-based foreign correspondents. Saturdays I would go to the office and catch up with friends later in the day. Sunday was the difficult one. There was little to do in the early part of the day. In the evenings, there were always the movies.

Solitude reunited me with my Catholicism and I became a regular at the nearby Holy Family Minor Basilica. One Sunday morning, the start of the Mass was running late and we shifted uneasily in our seats. The reason quickly became clear: President Kibaki was attending the service.

Still recovering from his road accident weeks before the December 27, 2002 general election, he hobbled in. There was little fanfare about it. He was led to the front pew and we got on with the Lord’s work.

After Mass, the priest said the President would now “greet the people”. That means a 30-minute harangue from an African president. Kibaki got up and said hi. It took about a minute. And he limped out. How? Some West Africans might have said the man had been bewitched!

I was already perplexed that we had walked into the church without a security check at the entrance into a service that the President was going to attend. And there were no beefy men with things sticking out of their ears inside the church.

Stayed out of sight

We were into the post-9/11 world and in the throes of the “war on terror”. At home in Uganda and in other places I had been in Africa, the presidency was a fortress.

A short while back, I had been to the Zimbabwean capital, Harare, for an international media conference. Then-President Robert Mugabe came to address the gathering. Among his 20 guards were two carrying machine guns with several bullet belts wrapped around them. They stood at the back. That was the ‘A’ game in presidential security. Kibaki wasn’t serious.

Yet it signalled what was to become one of the most unusual cases of an “anti-politics” politician in Africa. Though it has a much longer history, “anti-politics” came into popular usage at the start of the 1990s, loosely meaning politics and politicians who go against the practices and frills associated with traditional politics. That can range from lifestyle to policies.

Kibaki had been in politics virtually all his post-college life — as an MP, Cabinet minister and Vice-President for 10 years, from 1978 to 1988, under President Daniel arap Moi. He ran for president in 1992 and 1997 and lost his shirt both times. He triumphed on the third shot. If there was an Establishment politician, Kibaki was it.

But he didn’t govern as such. Part of it was age. He made good use of his long years. First, he avoided the political ring. Kibaki took on the air of a pope and never openly engaged in a political slugfest with his opponents. Secondly, he just shut up and stayed out of sight. Three months could pass before what he had done or said was a lead item on TV or in the newspapers.

His government, too, became plagued by corruption and was accused of tribalism.

Competent meritocracy

His genius was in engineering competing sunny narratives and realities. He generated a strong democratic smell in the Kenyan air — despite the occasional takedown of the media. His was the golden age of Kenyan freedom, which his rivals used to exhaust themselves in feuds and rants, living him largely unmolested in State House, only with the handful of First Lady Lucy Kibaki to contend with.

Kibaki oversaw a dizzying Kenyan economic comeback. Kenyan prestige and standing in the world cleaned up rather well. Then, while his old buddies and inner circle corruptly ate the fruit at the top of the tree, in the second tier of government Kibaki created a competent meritocracy which brought the bacon home.

In December 2007, it went horribly wrong with the election fiasco and the deadly post-election violence that followed. But even in a crisis, his ‘invisible’ ways came into play. Nobody accused him of personally overseeing the heist. It was presumed that the election was stolen for him, and he reluctantly went to that controversial and unusual swearing-in in the middle of the night.

And when his trousers fell to his ankles as he addressed a rally at the pulpit, it was embarrassing, yes, but it made him look like the lovable, relatable, clumsy uncle or grandfather we all have.

Kibaki died on April 21, 2022. He was 90. He must have gone happily. It had been long since somebody cussed him out.

Mr Onyango-Obbo is a journalist, writer and curator of the “Wall of Great Africans”. @cobbo3