Philip Ochieng the fallen hero, gothic towers and love of unseen things that don’t die

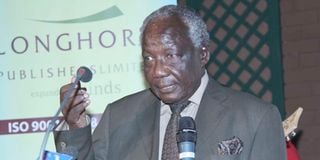

Philip Ochieng during the launch of his biography written by Liz Gitonga-Wanjohi at The Stanley on August 21, 2015.

Philip Ochieng, our late grandmaster of letters, lived a life of immense accomplishment and eternal struggle. A scion of early Anglican elites, he was firmly on the fast track to the heart of the colonial and post-colonial elite.

He joined Alliance High School as the country heaved in the throes of anticolonial ferment, and fell into the stern hands of the iconic Edward Carey Francis. Indeed, it may be said that Ochieng suddenly found himself in the middle of too much.

A Luo youngster in the middle of Kiambu, in the middle of Evelyn Baring’s State of Emergency, in the middle of a fine tension between an exacting missionary and a vicious colonial administration keen to exterminate all expressions of autonomous African aspiration.

This tension inscribed itself in Ochieng’s mind, as he navigated the existential contradictions that at once tore his world apart and made it – and him – up.

Alliance, heavily saturated with protestant Christianity, was an extension of his home and lay on the same authoritarian continuum as the colonial state.

Teenage rebellion sometimes extends into the exploration of taboos, as well as a nihilistic questioning and, sometimes, subversion of all authority.

The young Africans who risked their all to overthrow the British Leviathan must have impressed him profoundly, and Ochieng fell out explosively with Francis.

However, two years later, Ochieng was part of the inaugural airlift that would take him on an excursion in the citadels of global hegemony.

Imagine this moment, then; a personal intellectual awakening at that brilliant dawn within another, greater national dawn. Wordsworth has the expression for it: “Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive, But to be young was very heaven!”

He avidly fed his boundless hunger for knowledge, immersing himself with prodigious capacity in eclectic pursuits.

Thus, he became an academic nomad, leaving several degrees uncompleted.

Ochieng’s struggles – with Carey Francis, Christianity, God, colonialism, authority and hegemony – were, in reality, a single enterprise. Mustering his rich intellect, he deconstructed all expressions of unjust domination with awesome analytical dexterity, owing fealty to reason alone.

Ungovernable, footloose and fancy-free, his sojourns blew him across continents, driving him headlong into epicurean quagmires.

When my callow cohort struck out at our own blissful dawn of intellectual awakening, Ochieng was in full bloom.

He was our teacher, sage, model and leader. He was our ideal: erudite man of the world, courageous voice of reason, intellectual of tremendous rigour and a communicator of impeccable virtuosity.

His work bore the hallmarks of a refined cosmopolitan, an implacable idealist and a man of incomparable discernment, who relentlessly waged righteous battles, handily winning them all.

Kanu’s despotic nadir

Along the way, Ochieng became entangled with Kanu at its despotic nadir, scandalising the liberal intelligentsia.

His whys and wherefores will always be debated; he maintained that he was professional, ethical and parsimonious.

Kanu’s execrable party and government duopoly may have executed the sleight of hand that, per Kipling, challenged Ochieng: “If you can bear to hear the truth you’ve spoken, twisted by knaves to make a trap for fools.”

In any event, Kenyan politics, ever red in tooth and claw, was afterwards unforgiving to Ochieng.

Ultimately, he was a liberal thinker who demonstrated the reach of reason as a powerful driver of human enlightenment and progress. Moreover, he was a prominent exponent of excellence in all domains, steadfastly advocating the pursuit of knowledge as a good for its own sake.

He summarily condemned mediocrity and corruption, insisting that nothing prevents us from ascending to exemplary standards, in thought and word and deed.

Parallel to his Alliance classmate, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Ochieng embarked on an odyssey of decolonisation, upon the understanding that the mind is the most consequential site of the freedom struggle. National civilisation is founded on the quality of reasoning among its citizens, especially the elites.

By our indifference to reason, and oblivious cleaving to mediocrity, we renounce what makes us human, prefer instead the ways of Tennyson’s beast, “unfettered by the sense of crime, to whom a conscience never wakes.”

President Barack Obama’s lyrical adoration of the great American experiment is a living ode to the greatest civilisational accomplishment of the modern era: the self-conscious design of America as the expression of the highest human ideals.

Above the doorway of Princeton University’s McCosh hall is inscribed a telling epigram: “Here we were taught by men and gothic towers democracy and faith and righteousness and love of unseen things that do not die.”

The paucity of a self-consciously aspirational public aesthetic must lead us to seriously contemplate the thoughts of Kenya’s foremost evangelist of excellence.

Dismal national standards turn us into abject, outward-looking beggars and importers. Great societies are not accidental, and ideas matter. Philip Ochieng reminds us that excellence is our collective obligation, and that we must imagine our way out of mediocrity and corruption, as we did under the constitution of Kenya, 2010, and commit, with Ulyssean resolve, to strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.

@EricNgeno