Because national resource revenues are finite, we must plan for the time when the resources will have been depleted.

The new mining minister Hassan Ali Joho has raised the alarm over the exploitation of our strategic minerals. He put out a press release the other day charging that unscrupulous individuals have been prospecting strategic minerals — mainly copper, coltan and chromite in disregard of the law.

He did not elaborate. The truth of the matter is that this country is rich in strategic minerals. The reason we are not exploiting them is because corrupt elites have colluded with international players to keep most of the minerals in the soil by making sure that only small quantities needed to lubricate the lucrative underground trade reach markets.

Just the other day, we read in the international media how a UK company had acquired manganese assets in Kilifi . It was disclosed that the company had signed up for 30,000MT and additional ores of up to another 30,000 monthly of manganese ores. It was disclosed that — at full capacity — the 60,000MT monthly production will amount to annual production exceeding 600,000MT of manganese,

To appreciate what these statistics mean for the ordinary citizen, in terms of the opportunity cost, here is some context.

The world’s largest producer of manganese, South Africa — which accounts for 33.5 per cent of global manganese production, produces 6.1 million tonnes of manganese annually which generated for it USD 2.9 billion in export earnings in 2022.

Going by these statistics, it means the Kilifi manganese ores would amount to about 10 per cent of South Africa’s annual production or about 3.3 per cent of global output.

Access to strategic minerals

In April, we also read from the international press that the UK company had also acquired 60 per cent manganese mining operations in Samburu County. It was disclosed that the output of high-grade manganese from Samburu was about 50,000MT monthly. The riddle is that this activity does not appear in official government statistics. Kenya reported a paltry USD 18 million in manganese exports in 2022, virtually all exports going to China. Manganese is a strategic mineral for industry as well as the global energy transition because it is used in production of steel and batteries.

We must pursue our national strategic interests when it comes to strategic minerals.

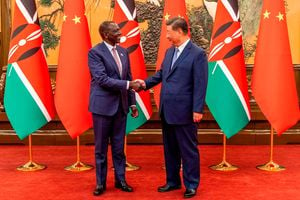

The fight between global powers for access to strategic minerals will intensify especially in the context of the global energy transition. The Chinese are big players in this space.

We all remember how in June 2020, Kenya signed an MoU with the Chinese to do a comprehensive geological survey of all minerals on our land. The MoU was to result in a nationwide remote sensing, airborne geophysical survey. I checked the records in our external debt register and confirmed that we indeed signed a Sh7 billion loan with Exim Bank of China to fund this project.

Somewhere along the line, some people high up in the regime of former president Uhuru Kenyatta advised that it would be foolhardy for Kenya to allow mineral-hungry China to be the one to collect this critical data. A decision was made that the task be conducted by our own military’s engineering corps after the government came to the realisation that the military had capacity, having trained a core of its engineers in international institutions on mineral mapping.

Highly-valued and rare mineral

I gather that when the military’s engineering corps completed the process, it was decided that because of the national security and strategic national interest the results were to be disseminated at a secret Cabinet meeting that was held at a secret security installation within Tsavo National Park near Manyani.

That airborne study discovered a total of 970 mineral occurrences in Kenya. In terms of critical and strategic minerals, the study revealed deposits of the highly-valued and rare mineral coltan in Tana River, Isiolo, Embu, Samburu and West Pokot. It found copper in Migori, Makueni and Tharaka-Nithi, graphite in Taita-Taveta, Embu and West Pokot, Nickel in West Pokot and Kilifi, rare earth elements in Kwale, Samburu, West Pokot and Kericho and manganese in Kilifi and Samburu.

This is the context in which Joho’s recent public statement must be understood. The truth is that corrupt elites have been minting billions by hawking the results of the survey to greedy international players.

What must we do? This space is not enough. But in terms of management of natural resources revenues, we must go back to the idea of establishing a sovereign wealth fund. In 2013, the Presidential Task Force on Parastatal Reform suggested that we establish a sovereign wealth fund. It was swept under the carpet.

Because national resource revenues are finite, we must plan for the time when the resources will have been depleted. Hence, the wisdom of transforming natural resource revenues into long-term financial assets that can generate revenues in the long term when the mineral runs out.