Jitters over Covid-struck Museveni

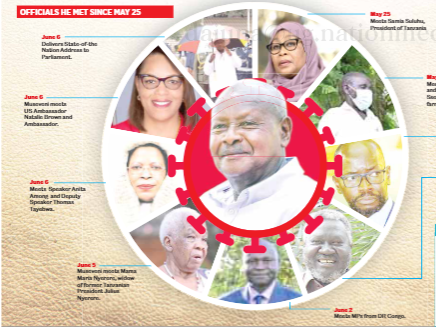

Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni. Last week, President Museveni went into isolation after he tested positive for Covid-19.

Last week, Uganda’s President Yoweri Museveni went into isolation after he tested positive for Covid-19. A late-comer to social media, which he used to despise, Museveni has become a prolific and adept user in recent years and amassed a large following.

No 78-year-old (and older) African president plays the social media game better than Museveni. In 2020, as the world was in Covid lockdown, he broke the internet with famous videos of him doing exercises and putting down 30 press-ups. There are whispers that he keeps a close eye on the “likes” and “retweets” and, from time to time, takes time to answer some of the posts critical of his rule and to give high fives to those who compliment him.

Not surprisingly, he took to Twitter immediately after his personal physician and permanent secretary in the Ministry of Health, Dr Diana Atwine, confirmed his positive test to break the news. Then he posted daily updates. Thus, he could control the narrative about his ailment and cap the inevitable rumours about death that follow big men’s ill health.

But social media is a treacherous territory and snake pit. A perceived delay in update fuelled rumours that his condition had worsened. Museveni also got too clever. He was the last leader still wearing face masks. When he went into isolation, he was still meeting with his officials, visiting foreign dignitaries and family members, and sitting anything from three to 10 metres apart. He is the only leader who beat Russia’s Vladimir Putin in the latter regard.

For someone so paranoid about the coronavirus, the debate about how he could have got Covid soon became spicy. He had also raised eyebrows in his first update, revealing that the face mask gave him bad allergies, and during the last Ugandan election campaigns (late 2020 to January 2021), he had got a bout of allergy and lost his voice. Suddenly, it looked strange that the man who was made sick by the face mask was also a mask fundamentalist. Noise about “there being something else more serious” with him started emerging.

It was a situation ripe for fake news and conspiracy theories, and they came via a post from a handle purporting to be that of a leading Kenyan broadcast media company. On a closer look, it wasn’t. But who lets such small things get in the way of a good tale? Within hours, the story that Museveni had been rushed to the intensive care unit with his life hanging by a thread swept the social media universe.

Sneaked into hospital

An update from his page came early evening when it was too late. Then, on June 12, there was no update at all. In the Kenyan rumour mill, claims began swirling that Museveni, much like in the alleged case of the late Tanzanian president, Dr John Magufuli, in 2021, had been “sneaked into a Nairobi hospital”.

General Museveni had ridden the social media tiger and ended up in its mouth. The former guerrilla leader has ruled as a velvet-gloved autocrat for 37 years and has many enemies and ill-wishers. One would expect them to celebrate his illness. But the news was met mainly with disquiet.

That is because, beneath the outward confidence that Kampala projects, its elite are fully aware that it’s built on very fragile ground. In the nearly four decades in power, Museveni has hollowed out the Uganda state and created a personalised security apparatus and patronage machine around him where power is concentrated.

There is no real-world transition structure in a country that, since independence in October 1962, has not had a peaceful transfer of power, either at the polls or through an internal party succession. Nobody is deluded that the provisions in the Constitution, which slate the Vice-President as the successor in case the incumbent dies or resigns, will prevail.

Makerere University lecturer Yusuf Serunkuma, writing in the Ugandan political publication The Observer, in an article entitled “Why we ought not to wish M7 sudden death”, noted the irony of the situation.

“Museveni has nothing to show for his near-forty years in office except debts and potholes. But if there are any lessons we could take from [Muammar Gaddafi in] Libya (and now Sudan under bombs and bullets), it is that long-staying presidents drive their countries to that breaking point where, ironically, only they can hold the country together.

“That point where their sudden demise is as bad (or actually more dangerous) as their continued hold onto power. I know it is a difficult position that a single individual invites a great many interests—from his deliberate and selfish long-stay—to coalesce in his personhood that his sudden death portends into violence on the national scene.”

Serunkuma is wrong that all Museveni has to show for his rule is debts and potholes. He took a broken country and, at one point, made it a shining star. But he’s right to portray him as the lion that ate its cubs. The revolutionary who hung around too long and ate the revolution.

Mr Onyango-Obbo is a journalist, writer and curator of the “Wall of Great Africans”. @cobbo3