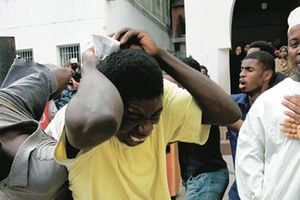

John Okello, a one-time field marshal, walks along Kampala Road in Uganda. Okello rose from a carpentry workshop to capture the world's headlines when he led a revolution against the former sultan of Zanzibar in January 1964.

Goa had always been the final destination for my family whenever I took leave to go overseas during my service with the colonial-era Kenyan government. However, just before Kenya’s independence in 1963, the government was offering generous cash inducements for officials choosing to spend their leave within East Africa.

My maternal uncle and his family, who had lived in Zanzibar for many years, were always inviting us to spend our holidays with them. Besides, this was the place where my mother grew up, and where my grand uncle (Fr Lucien D’Sa) was the first non-white Holy Ghost missionary of the Catholic Church. We accordingly seized the opportunity, and after spending Christmas with a dear friend, Bis Noronha, at his palatial Oyster Bay residence in Dar es Salaam, Tanganyika, we flew to Zanzibar on Boxing Day.

From the moment we touched down on this clove-famed island, we fell in love with the place and even decided that this is where we would retire to when the time came.

Hardly did we know that fate would decide otherwise! We enjoyed our daily trips to the seafront, picnic to Mangapwani Beach, and the friendly atmosphere that prevailed everywhere. Outwardly at least, the different races seemed to get on well together.

All this was to change though on the morning of January 12, 1964 — just a month after the island had attained independence from Britain. My uncle and I had just returned from church, and my wife Elsie together with my aunt were all ready to leave for a later service (it being the feast of the Holy Family). We asked them to be particularly careful as the priest during our Mass had warned of impending trouble.

Heavy gunfire

They had not even reached the front door on returning from church, when all hell broke loose as the sound of heavy gunfire filled the air. While previously everyone went about their business without fear, an eerie silence seemed to descend on this once peaceful isle. I was very concerned as the powdered milk supplies for our youngest baby daughter (Josey) were fast running out.

To add to our problems, Andrew, our second son, had developed whooping cough. From the intermittent messages broadcast from the local radio station, it soon became apparent that a young Ugandan soldier, the self-styled “Field Marshall” John Okello, had overthrown the government of Muhammad Shamte Hamadi in a bloody revolution to rid the island of the Sultanate Arab rule.

All communications with the outside world had been cut off, but the BBC World Service remained on air as our main source of news. All we could hear was the roar of vehicles and the shouts of what appeared to be drunken, trigger-happy men. The Sultan and his family, who were threatened with death, had escaped by fleeing to neighbouring Tanganykia where Britain made arrangements for their safety. What happened to Prime Minster Shamte was not immediately known.

The local radio station broadcast intermittent, albeit confusing, messages. At one stage we were all told to remain indoors. Later, “Field Marshall” John Okello broadcast an order asking all traders to open their shops to enable people to buy essential goods. Those venturing out were asked to wear a distinctive-coloured armband to signify their approval of the new government. I plucked courage to shop for Josey’s baby food and other essentials, and despite being challenged by what to me appeared to be untrained and undisciplined ‘soldiers’ I managed to get home unharmed and in one piece, but visibly shaken.

Sporadic shooting continued and since my uncle’s house was close to the cable and wireless station and American Embassy (obvious targets), several of the bullets whizzed past our window. We spoke in low tones around the house and even had to try and get Andrew to suppress his cough as armed groups were going around from house to house and we didn’t know what to expect. We were all in a state of shock. While shopping that morning, however, I’d met an Englishman who told me that there was to be a meeting at the English Club where the British High Commissioner would advise on evacuation arrangements. I attended the meeting where the High Commissioner Timothy Crostwait attempted to allay people’s fears by announcing that those willing to leave would be evacuated by the Army.

Revolution started

As my uncle and aunt were reluctant to leave (having lived in Zanzibar for years), we decided to stay put, and if need be perish with them! It was fortunate that our eldest son (Clyde) and cousin (Naty) had left for Nairobi to return to school well before the revolution started.

We had heard stories of a massacre in the predominantly Arab quarter, which we had visited a few days earlier. Some friends of my uncle had also lost their lives.

When some semblance of normality seemed to return, I visited the local post office to send some of the letters I had been writing to family and friends. I was not allowed to use independence stamps on these letters unless they (the postal staff) first crossed out the Sultan’s head! Some days later, they had managed to rubber stamp all stamps across with the word “Jamhuri” (meaning Republic). I bought a few of these new stamps as I was a keen collector in those days.

The previous carefree attitude was no longer visible. People now moved about more cautiously. An air of suspicion seemed to hang over the whole island. From contacts, we heard harrowing accounts of looting and death. What was once a bustling place took the appearance of a ghost town.

Since my uncle and aunt were reluctant to leave despite the trauma of the revolution, we decided that we should now spend the remainder of my leave with relatives in Mombasa.

We flew back to Dar es Salaam where, after a few days’ stay my cousin Nico Pinto, drove us all the way to Mombasa. Many of our relatives and friends were pleased to see us, especially since some had given up all hope of seeing us alive. I was later to learn that my good friend Robert Ouko — then attached to the Foreign Ministry in Nairobi and later to become Kenya’s Foreign Minister — played no small part in making enquiries about us and our situation. On returning to my job in Njoro after a relaxing few days at the Coast, I was able to write and thank Robert for his efforts on our behalf.

When we set out on our East African holiday, I had never imagined that we would encounter a situation like the bloody revolution we had just been through. To come out of it without a scratch is nothing short of a miracle!

‘Field Marshall’ John Okello’s fate and how the revolution changed Zanzibar are stories for another day.