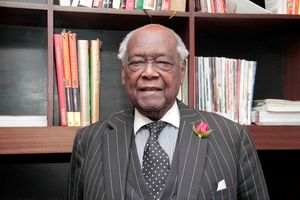

Kabucho Wakori.

During the Njonjo Commission of Inquiry, as Kenya’s most potent politician was humbled, one man stood out – Charles Njonjo’s driver, Kabucho Wakori. Not only did he insist on speaking the Gikuyu language – and the Justice Miller Commission had to look for an interpreter – but he emerged as one of the trusted personalities within the Njonjo circles. In the Kenyatta and Moi era, there were powerful personal drivers – and there was Kabucho Wakori.

When he died last week, Wakori went down with a story of his dalliance with Njonjo. If anyone understood Njonjo’s world, that honour may not be within his elite circles but with his chauffeur.

This man had mastered the power games and could penetrate any corridor as he spewed orders and overrode the bureaucratic tapes. To enjoy the privileges that came with his designation as a driver, Wakori was elevated to Chief Inspector of Police – a title that allowed him to carry his weight around.

When Njonjo was found guilty of stashing an “inordinate quantity of firearms and ammunition together with installation of ground-to-air and air-to-ground transmitting radio equipment,” the name of Wakori was mentioned alongside the billionaire Yani Haryanto family of Indonesia. Others named in the same racket were the Central Firearms licensing officer and Senior Superintendent of Police Douglas Alan Walker.

Solio Ranch

Walker and Wakori would receive expensive firearm gifts from those who wanted to short-circuit the licensing and weapons storage bureaucracy. The Haryantos had an interest in the Solio Ranch, where Njonjo was also a director. They were game hunters too, even after it had been banned. In order to possess the 17 guns, the Haryantos had been appointed as “honorary game wardens”.

Interestingly, although he was designated as a Chief Inspector of Police, Wakori told the Commission that he never went through any police training and did not have any formal education. Being close to power helped him.

Apparently, he had been employed in 1958 as a police constable, which places him within the colonial police workforce. Wakori’s literacy, by 1980s, was limited to writing his name. Why Njonjo trusted him – given his suave mannerisms tells the other side of Njonjo – and by the time of the Njonjo inquiry, Wakori had enrolled into adult literacy classes.

It was Wakori who revealed another side of Njonjo: That Njonjo used to import oranges, apples, clothes, and Ribena from abroad! Wakori would go to the airport to pick up the unaccompanied luggage. Between 1966, when he was assigned to drive Njonjo, and 1972, Wakori said that he used to collect an average of two suitcases from the airport, but when Njonjo got married, he would pick an average of three suitcases from the airport a month.

Wakori would also get instructions from Njonjo’s secretary, Miss Penelope Warren-Hill or Captain Boscovic, on which visitors or luggage he was supposed to pick. He would take the guests – especially the Haryanto’s sons and wives – through the VIP lounge, although they were never entitled to such privileges. More so, as Zabron Munyasya, the airport security officer, revealed, Wakori had never been issued the special pass that would have allowed him into the VIP lounge. The title of Njonjo’s driver was, most likely, enough Pass. This view was supported by the evidence of Essau Kioni, a former security services manager of Kenya Airways who said that Njonjo’s unaccompanied baggage was given special treatment. Wakori used to collect Njonjo’s baggage directly from the aircraft without going to the baggage hall.

According to Kioni, he could not recall any other person who enjoyed such privilege: “Njonjo sometimes could enter the airport through some gates that were not used by other customers…Sometimes he could go through the gate near the cargo area…Sometimes he could reach the aircraft through the old airport.”

Showcase power

Kioni would later be fired after he advised KQ’s revenue accountant to bill Njonjo for excess baggage weight of 270 kg. After the invoice was raised and sent to Njonjo’s office, his (Njonjo) business ally Lord Cole – then the managing director – had it cancelled. Wakori was part of this network that Njonjo had put in place and the airport was a small playing field to showcase power and hubris.

Being a policeman did not entitle Wakori powers to shepherd Njonjo’s guest through the airport’s restricted spaces. For instance, the VIP lounge was only reserved for Cabinet ministers, High Court judges, Permanent Secretaries, Provincial Commissioners, High Commissioners and ambassadors, directors of statutory boards on request, army commanders, the Commissioner of Police, and the Commissioner of Prisons. It was not for ordinary visitors – no matter their monetary weight. (The only other time that lounge was abused was by the Turkish bling-bling busy-bodies Artur Magaryian and Artur Sargasian during the Mwai Kibaki presidency!)

The other story was about Ms Warren-Hill, who worked for Njonjo without a work permit between 1975 and November 1982. Njonjo had contracted an agency in London to hire a secretary for him, and that is how Warren-Hill, previously working in Italy, ended up as the Attorney General’s secretary.

The Njonjo driver’s mission was to make sure that the Haryanto’s luggage did not go through Customs. More so, Wakori – always in police uniform - would take their passports to the immigration while the luggage was put in the vehicle.

One of the vehicles was a GK Land Rover – by then a symbol of power. At one point, the Firearms Bureau boss, Sgt Walker, would go the airport to clear the guns. Again, that such a senior figure would find his way to the airport to clear guns for some guests illustrates how raw power was mobilised and exercised in those days. At one point, Wakori was given an RG-14, also known as a Saturday night special, described as a cheap, low-quality handgun. Although a policeman, Wakori had been trained briefly by Senior Superintendent Walker on how to use a pistol. His police training ended there.

Interestingly, while Wakori was transferred to the Presidential Escort, as a member of the Transport Section, he continued to be Njonjo’s driver. Why? Only Njonjo knew what that meant. As he dodged questions during the Njonjo inquiry, Wakori became the master of twisting facts and evading questions. Justice Madan lost his cool: “Mr Wakori, I think …you have been treating us as individuals of childish simplicity – as people who know nothing at all. It is not our custom to tell the witness that he has been very kiddy or not telling the truth or unpleasantly, he had been telling lies. That is not our way.” It was Wakori, in police uniform, who was on standby when some Americans arrived with boxes containing guns, which had been labelled as “fishing rods and camping equipment.” Julius Angwenyi, the assistant security manager at JKIA, could do little; after all, Firearms Bureau boss Alan Walker was there to issue an import licence after the fact.

When he recently died, Wakori disappeared from the limelight, and like Njonjo, he enjoyed his retirement in peace. If there is one man who enjoyed – and witnessed – the raw power in Njonjo’s world, it was Kabucho Wakori. Even today, when an advert appeared in these pages announcing his death, many of my readers here reached out.

They can vividly recall that Wakori had become a historical figure. When Njonjo’s story is finally written, Wakori is a person who would get some space. That means that Njonjo’s world was not only about elite, well-groomed, and learned figures. There were specks of Kabucho Wakori who managed the raw power. May he rest in eternal peace.