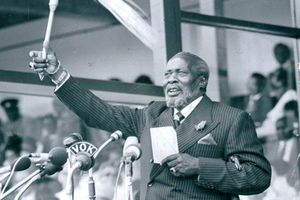

Mzee Jomo Kenyatta and his wife Edna.

Archives on Edna Kenyatta reveal a woman that Kenya quickly forgot. As the country celebrates yet another Madaraka Day, the story of Edna Kenyatta and her place in Kenyatta’s struggles remains muted.

Let us walk through some of the letters.

Her story, however, started tragically in May 1941; both her parents had been killed during an air raid in Britain during the Second World War. According to Jeremy Murray-Brown, who authored Kenyatta's journalistic biography in 1970, Kenyatta offered the woman the necessary sympathy.

“He accompanied her on the train to Yarmouth to attend the sad business of clearing up. Returning alone to Sussex, Edna welcomed the protection of Kenyatta’s warm and powerful personality,” wrote Murray-Brown on how the love affair started.

Kenyatta was nicknamed Jumbo by the locals. He would walk around, sometimes carrying a spear and wearing a Colobus cloak!

One year after that bombing tragedy, Kenyatta and Edna were married at the Chanctonbury Registry — though Kenyatta had to concoct a lie: that he was a bachelor, though he had a wife, Wahu, and two children, Muigai and Wambui, in Kenya.

He also had to estimate his age, and according to Edna’s papers, he may have pushed the age lower. Worried after Kenyatta went back to Kenya and got arrested, Edna was the target of the English press — after they found out that the man they had claimed hated “Whites” had indeed married an English lady. In November 1952, one of the MPs, Fenner Brockway — writing to Miss Dinah Stock, a long-time Kenyatta friend based in New Delhi — said: “His English wife has stood by him firmly and made statements to the English press exactly on the lines of your letter”. That meant confronting the negative English press was no longer a domestic issue.

Pseudo-name

It called for a joint effort to protect Edna for the second time. Kenyatta’s first letter to Edna was dated June 28, 1953, and addressed to a pseudo-name:

Mrs E. Kay. It was posted on July 14. Another letter from Jomo had Edna's name, Edna Ken. Dinah Stock, who was known to Edna, became the conduit between Kenyatta and Edna. “I wrote to Edna at the address you gave me but have had no reply. I don’t know what happened, whether she received my letter or not. Have you heard from her lately?” Kenyatta inquired in his November 17, 1955, letter. “If not, I would like you to write to her and find out how things are.” Kenyatta received the address in June 1955, meaning it had taken him five months to wait for a reply. We don’t know whether this was a way of breaking him psychologically. Friends would contact Edna and then write to Kenyatta.

Writing again on January 24, 1956, to Diana Stock, also known as A.G. Stock, Kenyatta said:

“I have heard from Madge. She says she has been in touch with Edna and that Peter is getting on well with grammar school. I am going to write to her soon.” Kenyatta knew that his letters were disappearing — not only to Edna but also to Edna’s contacts like Dinah Stock. On December 27, 1957, Kenyatta asked Dinah whether she had received his previous letter: “As I had no reply from you, I assume that the letter did not reach you, so I am now writing this with the hope that this will get to you.” Jomo was always desperate to reach Edna while he was incarcerated at Lokitaung. His friend, Geoffrey Husbands, would receive Edna's letters. “When you see or write to Edna and Peter, please give my kind regards,” he wrote on August 10, 1957.

When Edna's letter arrived, Kenyatta wrote back, “The news from you gave great comfort and consolation to my soul. According to Murray-Brown, Kenyatta would read Edna’s letter over and over again till it cast its spell over him and carried him back in spirit to Storrington.” In another letter dated March 5, 1958, we learn that Kenyatta had written another letter to Edna through Mr Husbands.

On August 12, 1959, Kenyatta wrote again to Mr Husbands.

Marching to freedom

“I am glad to hear that you have been seeing Edna and Peter and that you have passed my letter to them. I hope that Peter has passed his exams. I wish him every success. Do give them my love, they do not write, I do not know why. I would very much like to have a full-size photograph of Magana, that is in a standing position, I do not think that he will mind giving a good smile for his daddy… life here is a continuous monotony, heat and dust shout their hallelujahs daily.” Kenyatta did not know that the Intelligence was confiscating some of his letters from Edna.

Edna Kenyatta cuts a chocolate cake specially made in honour of her visit.

Shielding her son from the political heat that had engulfed her family — and the ‘traitor’ title bestowed on her for marrying Africa’s number one “terrorist” became an obsession. Kenyatta had also asked Dinah to follow up with the publishers of Facing Mount Kenya to release the money to Edna to pay for Magana's school. According to his biographer, “no money ever arrived”. Edna was not apolitical.

She was so excited by the wind of change blowing in Africa that she wrote in July 1960:

“It is comforting to see that there are clear signs everywhere that Africa is slowly and surely marching to her freedom.” When Edna attempted to get a passport for her son Peter, the Colonial Officer started harassing her. According to Dianah Stock, Edna was held up for three hours until a man from the colonial officer came over and stood over her shoulder, watching every word she wrote. From Edna's papers, we learn that Jomo was writing an early autobiographical work of fiction about “Kajomo and Wambui”. Edna's life with Jomo was filled with love during wartime. Jomo had to take odd jobs at the flower farms and worked as a part-time lecturer for British troops on anthropology.

Leave for Africa

Edna knew from the beginning that Kenyatta would one day leave for Africa:

“I have no intention of spending my old age in England,” he had told Edna. As Edna told Murray-Brown, Kenyatta was “a wily old bird. Maybe he knew he was going back to Kenya as soon as he said that”. When Kenyatta became Prime Minister, we learn that he asked Edna to stop working and suggested that she could work with children in Kenya. As Kenya became independent in December 1963, Edna was one of the special guests invited. Western press beamed her photo as she was met at the airport by Kenyatta’s “wives”. The Associated Press story said, “Mrs Jomo Kenyatta No.3 welcomed Mrs Jomo Kenyatta No. 2… and both went off happily to meet their husband — Kenya's Prime Minister.

On Edna, they said, "It is rumoured she may stay and take her place in the community”.

The wire story lied to its readers, saying Kenyatta had “more than 20 children”. But Edna did not stay. She left after the celebrations as Mama Ngina took the position of Kenya's First Lady. At times, Edna felt a bit neglected, as she told Murray Brown. However, she still signed her letters as Edna Kenyatta, though she never used the name to open doors. It is unknown how race relations in Kenya would have been had Edna stayed — and more so if she had become Kenya’s First Lady. Little is known about the engineer’s daughter whom the Kenyan activist smote.

As more archives and letters emerge about her, we are slowly learning about the woman that Kenyans almost forgot.