Life after Li Keqiang, the Chinese Premier who oversaw SGR deal in Kenya

Then China's Premier Li Keqiang speaks during a press conference after the closing session of the National People’s Congress (NPC) in Beijing’s Great Hall of the People on March 15, 2019.

When Li Keqiang, the Chinese economist who until last month was his country’s Premier, bowed before delegates of the National People’s Congress, The Guardian described him as a ‘defeated man.’ But it may as well sound what the Communist Party of China would look like.

Li is the figure who actualised the Standard Gauge Railway (SGR), the first modern railroad line in the region meant to enable faster movement of goods from Mombasa to the hinterlands of East Africa. The project hasn’t followed the original vision of reaching other countries yet.

He was also Premier when China began the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China’s ambition to rebuild ancient trade routes with countries as far as Africa, as proposed by President Xi Jinping. He headed the State Council, which implemented the country’s macroeconomic policy. Under Li Keqiang, the country focused more on internal consumption, rather than a total export economy.

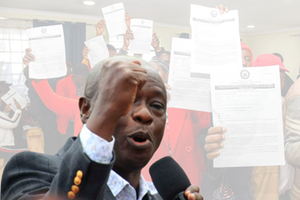

Nearly nine years after the signatures at State House in Nairobi, his retirement is being interpreted as an end of an era.

There are those who argue the SGR and other infrastructure projects signed in the last decade have helped pile debt owed to China, even though he is also credited with trying to balance trade and attracting investors into China.

Li was replaced by his namesake Li Qiang, a former provincial party chief with minimal experience in national governance and credited with the strict Covid-19 lockdowns in Shanghai last year.

But that replacement has been seen as both a reward for loyal Communist Party of China (CPC) chiefs, as well as a sideline for those who tried to upend the role of the Communist Party.

Last week, Li Qiang was quoted in Chinese media telling staff at the State Council, the organ that mimics the Cabinet in the West, to strictly serve the goals of the CPC.

Li Keqiang headed the Council for ten years, pushing for a separation between the state and private sector.

His retirement is now seen as a permanent stop to that ambition, returning the CPC into control of economic affairs.

“When deciding on complex economic policies, the government took into account varying inputs from local governments, think tanks and other stakeholders. After heated discussions, a well-thought-out policy would be implemented. This process may be skipped going forward,” Nikkei Asia reported.

That may mean bureaucracy will be weakened, something good for decision-making. Or that officials will turn into Yes men. And Xi's picks for top government jobs suggest the days of liberal reformers steering the economy have come to an end, while his track record of propping up the heavy industry and cracking down on big tech suggests a more state-led approach is here to stay.

While he has thrown his weight behind the development of a more consumption-driven economy -- a policy known as "dual circulation" -- his calls for addressing China's yawning wealth gap under the banner of "common prosperity" have gone quiet in recent months after giving investors the jitters.

With the United States promising to prioritise maintaining "an enduring competitive edge" against China as they battle for dominance over technology, Beijing may find itself under growing pressure internationally as growth slows at home.

Tensions with the US

Relations between Beijing and Washington have been on a steady decline in recent years, with the two sides butting heads over a number of issues including trade, human rights and the origins of Covid-19.

A planned visit by US Secretary of State Antony Blinken in February month was cancelled at the last minute after the United States shot down a Chinese balloon it said was conducting surveillance over US territory -- a claim strenuously denied by Beijing.

Since then, Chinese diplomats have kept up a steady drumbeat of anti-US criticism, with Foreign Minister Qin Gang this week warning of "conflict and confrontation" with potentially "catastrophic consequences" if Washington does not change tack.

Xi himself also made a rare direct rebuke of Washington this week, accusing "Western countries led by the United States" of trying to thwart China's rise.

The countries in question "have implemented all-round containment, encirclement and suppression of China, which has brought unprecedented severe challenges to our country's development", Xi said, according to state news agency Xinhua.

Taiwan threats

After ratcheting up tensions with Taiwan, an emboldened Xi could decide the time is right to fulfil Beijing's longstanding ambition of seizing the self-ruled democratic island.

China's sabre-rattling towards Taiwan has become more pronounced in recent years.

A visit by the then US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi last year prompted a furious Beijing to hold its biggest military drills around the island in years.

The Communist Party for the first time enshrined its opposition to Taiwanese independence in its constitution in October.

Any move to invade Taiwan would wreak havoc with global supply chains given the island is a major supplier of semiconductors -- an essential component of nearly all modern electronics.

It would also provoke outrage from the West, deepen China's isolation, bring Beijing and Washington closer than ever to direct military confrontation and snuff out Taiwan's hard-earned democratic freedoms.

China on Sunday said its military budget would rise at the fastest rate for four years, as outgoing Premier Li Keqiang warned of "escalating" threats from abroad.

Drew Thompson, a visiting senior research fellow at the National University of Singapore's Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, said the "sustained, year-on-year" spending increases made Beijing's claim that its military modernisation does not threaten its neighbours "ring hollow".

China's concurrent lack of openness is "destabilising" and "fuelling a cycle of worrisome deterrence signalling that China is quick to blame on other parties, without acknowledging its own explicit actions and policies", he told AFP.

China under Xi has seen the almost-total eradication of civil society -- scores of activists have fled the country and opposition to the government has been all but snuffed out.

In the far-western region of Xinjiang, rights groups say more than a million Uyghurs and other Muslim minorities are detained in what the United States and lawmakers in some Western countries have said amounts to genocide.

The situation looks unlikely to improve in the next five years as Xi's power grows increasingly impossible to challenge and the leadership digs in its heels against international pressure.