Why Nkaissery turned down President Kibaki's appointment after TV announcement

The then Internal Security Cabinet Secretary Joseph Nkaissery in April 14, 2016.

When we returned from America in June 1997, we found a gathering of Maasai elders at hand to welcome General at JKIA with one request: Could Brigadier Nkaisserry please resign from the military and run in the December 1997 election as the people’s candidate for Kajiado Central Constituency?

At the time, he told the elders, who followed us to our home at Lang’ata Barracks, that he had heard their plea, but they needed to consider that President (Daniel arap) Moi’s government had just spent a fortune on his year of training abroad.

He felt, therefore, he should remain in the military and apply the training for the benefit of the country.

That day in 1997, the elders accepted the explanation of their son and retreated.

Now, late in 2002, with just three months to the General Election set for December 27, the elders returned with the same request.

Chief Nkaru ole Seki remembers that General told the elders that they had to ask the President themselves whether their son could leave the military to join politics. What I remember of that period is that seven elders came to our home in Nairobi to ask General to stand for elections.

“Now what will I tell Moi?” General asked. He told me that the next day when he left for Nakuru, he was then the Commandant at AFTC (Armed Forces Training College), the elders followed him.

When he pointed them in the direction of the Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces, the President, they selected five elders to go to State House: Mzee Nailole, Mzee Mpoke, and Mzee Seki were in that delegation.

I heard later that the President told the elders and my husband that they had done well to select a new leader because William Ntimama and John Keen were getting on years and the Maasai people needed a strong leader.

“General, go and take that seat and be the voice of the Maasai,” Moi is reported to have said.

When they came home to deliver President Moi’s consent to General joining politics, Mzee Nailole was jumping for joy, quick to cast me in a new role.

“Helen! Tumesema. Amuka sasa (We have spoken. Stand up, start the campaigns).”

It is only recently that I learnt that General’s entry into the political competition in Kajiado Central caused serious friction between friends.

Our best-man, General James Mulinge, explains that he was called in to arbitrate the matter at Bull’s Eye.

James had been to Bull’s Eye just a couple of months before then, on the occasion when my husband surprised him with the gift of a cow.

General took James to our farm in Bissil and explained, “Jim, in our culture, the best-man must be given a cow and that is why we are here today, so many years later, I want to give you your cow. And you must touch it.”

Stunned by the gesture and feeling deeply honoured, James walked into the herd and touched the cow General had pointed at. Whereupon General said, “Now that is yours. I have finished my work for the day. Let us go to Bull’s Eye and enjoy our meat.”

“Our drive back was almost a bit quiet because I was a bit speechless now,” James says, recalling the unexpected gesture from his friend.

The two of them had passed through Bull’s Eye on their way to Bissil and James was a little surprised when General ordered five kilogrammes of meat. Wasn’t that too much for just the two of them?

When they got back from the farm, James says, “We sat at the front veranda, not inside. The meat was brought, so much meat. As the waiter started cutting it up Nkaisserry told me, ‘Sasa kwa kimaasai nyama haina mwenyewe. Nyama ni ya watu wote, kwa hivyo vile utaona hapa, wewe sasa nina-advise weka bidii, saa hii (In our culture, meat has no sole ownership. Meat belongs to everyone, so what you are about to witness – I advise you to start eating fast).’

And as he was saying that, other Maasai men started landing there, left, right, centre, from the mainroad where we had seen them. We were surrounded! Nkaisserry looked up, ‘You see, that’s what I was telling you.’”

James marvelled at the easy way in which General mingled with his people. On their drive back to Nairobi, they talked a lot about leadership, with James urging General to consider a change of career, perhaps a stab at the MP seat. “He didn’t say yes, and he didn’t say no either.”

On James’s second visit to Bull’s Eye, the crowd was at bay. James sat with General, our neighbours Titus Naikuni and Jacob Kipury, and Patrick Koinari ole Tutui.

The case before James was that a few months earlier, Tutui had approached the other three men, his fathers, as well as his older brother Noah and asked them whether any one of them was interested in vying for the Kajiado Central seat.

All of them said, “No”. They gave Tutui their blessings and he went ahead and resigned from his job at Kenya Ports Authority.

Now, a few months later, General had gone back on his word, thrown Tutui into a spin and left his friends Kipury and Naikuni with egg on their faces. How was the blessing to be undone?

James, then a Major-General, had been away in Tunisia on a work assignment when he got word that Nkaisserry had declared his candidature and had quickly been processed for discharge from the military after seeing the President to explain his decision.

General hadn’t informed him of the decision but when Kipury called him to arbitrate the matter, he saw the need and agreed.

“I told him to slaughter a goat, which I would pay for, and asked him to invite the other elders except Nkaisserry and Tutui. The candidates were not to attend our meeting because we were to discuss them … It was too late because Nkaisserry has resigned from the military also and has started campaigning. So how do you tell him not to go ahead?

“After a short discussion, I posed questions to them because my position was that the decision, based on facts, would come from them, not me.

“One, let us analyse where do we need this representation? It is clear you want somebody who can help the community, the development, their personal issues. Somebody who can reach government ministries to resolve programmatic issues in Nairobi and bring development to the community. Then the third point was okay, under the circumstances, what is the best way? If you give it to Nkaisserry, is he in a position to help Tutui who has lost his job? If you give Tutui, is he in a position to help Nkaisserry to regain his job? And the decision was very simple.”

Former Internal Security CS Joseph Ole Nkaissery addressing journalists at Harambee House.

Boundaries

Resolving things firmly was a hallmark of General’s character and it didn’t matter to him who got offended in the process.

One time, when I was fencing our ranch in Bissil, I took the liberty of extending the boundary to cover a no-man’s land. I was sure I was not encroaching on our neighbour Naikuni, and I was excited at the prospect of extending the pasture for our cattle a little.

When General saw the fence, he caught up with me at the point where I was supervising the work and thundered,

“Nani alisema mupite hii Olng’arooji (Who said you could cross this well)?

I said, “But this is no man’s land, so I am just increasing mahali ya ng’ombe zangu (pasture for my cows)”.

“Rudisha! Ero!” He called out to the workers, “Remove it,” he ordered.

“Rudisheni hii fence irudi mpaka huko! Sitaki mali ya mtu. Rudisheni (push this fence right back, I don’t want to take anyone’s land.”

When I look back at it, I realise that in saying ‘no’ to what I saw as innocent encroachment, General saved me from creating friction with our neighbour.

Naikuni was appreciative of General’s integrity. “It’s common to have a lot of issues as neighbours with boundaries around land. We never had that. Never!”

Given my husband’s position in government, I might have got away with the infraction, but General didn’t entertain any bending of the rules.

The direct way in which he spoke to me over my fencing is the straightforward way in which he approached any sticky issue.

Chief Joseph Leseiyo worked with him on many issues in Endonyo Enkampi Location. Leseiyo echoes General’s agemate, Moses ole Sekento, when describing this directness.

“No backstabbing. If he believed you were wrong or bad, he told you so to your face, at a baraza. ‘You are the one spoiling issues for the community’. Of course, everyone has detractors, those who will oppose you, but General would always disagree with you publicly.”

Sometimes, if he felt that someone had misunderstood him, or acted on information that was not accurate, he would either find an emissary to go and set the record straight, or he would defuse the rumour by doing something that would prove its inaccuracy.

He downplayed hostilities and he would tell me, “I am not going to waste time on small wars.”

One time, a political rival tried to incite voters by peddling word in a location that General did not support that section.

When he got wind of the story, General identified a road that needed upgrading, hired 50 young men from the area, using his own money, and put them to work. When they were done grading the road, he focused on the primary school along that road and initiated the building of two classrooms.

By showing rather than telling, General had proved that he had nothing against them. He was committed to uplifting their livelihoods. Though he stood by truth, General understood that people were fickle in politics, and didn’t care to remember tomorrow what they said today.

I recall one of our campaign managers telling General, “Please, stop being too truthful. A politician in Kenya is not supposed to say black or white. You’re supposed to say something in between.”

General’s response was, “If I don’t say something truthful, it will come around. And people will discover that it was not true. At that point you will not be there. It will be counterproductive. I better say the truth and let it be.”

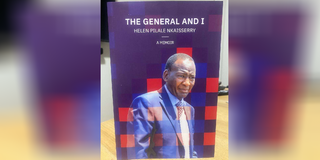

The front cover of the book.

No, Mr President

The person my husband was in private is the person he was in politics. Soon after his first electoral win, I witnessed this consistency in public.

There was a Cabinet appointment that brought us drama. Or rather, General’s reaction to the appointment spiralled into a national drama. It was December 2005.

Tensions had erupted in Narc within weeks of their 2003 presidential victory.

The National Alliance of Kenya (NAK) wing was accused of forging a Mt Kenya mafia that had swindled the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) wing of the Cabinet seats that had been agreed upon in the coalition’s pre-election memorandum of understanding (MoU).

By early 2004, there was strong talk in political circles that the president would be impeached.

Fearful that Narc ministers would join in the vote of no confidence, President Kibaki hatched a plan with Simeon Nyachae’s Ford People and, or so it was said, some Kanu leaders.

In his autobiography, Nyachae says Uhuru Kenyatta, who was the then Leader of the Opposition, attended that first meeting at State House where discussions with President Kibaki, Bonaya Godana (Kanu), Nyachae and Henry Obwocha centred on the formation of a government of national unity.

The GNU was announced on June 30, 2004, and it included Kibaki’s old friend Njenga Karume (Kanu), John Koech also from Kanu, and Nyachae and Obwocha from Ford People.

A few months later, Kibaki had to reconstitute his Cabinet yet again. This December 7, 2005 reshuffle was prompted by Narc’s humiliating defeat at the November 2005 Referendum.

When his “Yes” side lost, Kibaki reacted by sacking all “No”-affiliated ministers.

He worked without a full Cabinet for two weeks.

My husband and I were in the small sitting room of our Karen home when we heard General’s name on TV. He had just been named an Assistant Minister in the Ministry of Energy.

“Ala! How? I am not in Narc. No. But the party, Uhuru didn’t tell me that he has given out my name. What is this I am being given? If they wanted me to help in a government, if they really are genuine, then they would have given me something to do with security.”

Even though he had found himself in the opposition in his first term, General was determined to help its losing presidential candidate Uhuru Kenyatta rebuild the structures and popularity of the old party.

Now, he called Uhuru. Once his party leader confirmed that President Kibaki had not consulted him before announcing that appointment, General moved into action to reject the position.

He called up his contacts in the media as he explained to me, “You know, Mummy, I am not taking this thing. First of all, my party leader hajaambiwa (has not been consulted). Secondly, Assistant Minister for Oil and Petroleum? What do I know about this? Is it just that they want to weaken this party that I belong to?”

He was the first one to turn down a Kibaki appointment.

“His conscience and that of the Maasai was much more important than a mere Cabinet post, which would not sort out their economic woes” was part of his statement carried in the press the following day. “I am a man of principles and as deputy Kanu secretary, I will not take the position.”

The following morning, 11 other opposition MPs announced that they had rejected Kibaki’s call to serve in his government. General was not out to set a precedent, he just needed to draw a clear boundary in political party affairs. And he was very loyal. That was his nature. He was not going to walk out on Kanu for perks and prestige that would benefit him individually and leave his party depleted.

“Yes” to a new party

Eventually, however, the people of Kajiado Central made it plain that though they still wanted him as their MP, Kanu’s messaging was no longer resonating with their needs.

ODM was their party of choice. ODM had grown organically after the 2004 rebellion against Kibaki’s betrayal of his LDP counterparts in Narc.

By the time of the November 21 , 2005 referendum on a new constitution, Raila Odinga and Uhuru Kenyatta had joined forces to lead the populace in saying “No” to the draft constitution.

The symbol for the “No” vote was an orange and that for “Yes” driven by Narc and Kibaki was a banana. The Banana team was dealt a resounding defeat, getting 2.6 million votes as Orange racked up 3.6 million.

Emboldened by the victory, the Orange team declared the results were sufficient proof of the people’s loss of confidence in the government and demanded either a snap election, or President Kibaki’s resignation.

Neither of the two happened. Instead, Kibaki sacked the Orange ministers and constituted a bigger GNU, the one that General refused to serve in.

There was a lot of politics about how the 2005 draft constitution had been watered down from the original proposals.

When Narc came to power, Cabinet Minister for Constitutional Affairs Kiraitu Muriungi had promised a new constitution within 100 days.

Narc failed to keep that promise but agreed to continue with the work that had been started by the Ufungamano Initiative to craft a people-driven constitution.

As the MP for Kajiado Central, General was delegate No. 146 of the 620 delegates selected by the Constitution of Kenya Review Commission. They met at Bomas and produced what came to be known as the Bomas Draft.

General championed the defeat of what he saw as a flawed constitution.

At Bomas, they had worked hard to include recognition of indigenous cultures and the return of ancestral lands to communities in the draft constitution. But on the floor of Parliament and somewhere in government circles, proposals driven through Attorney-General Amos Wako altered that Bomas Draft significantly. What was put to the vote in November 2005 was the Wako Draft.

General could not, in good conscience, vote for it or ask the people of Kajiado to support it. He had, after all, been working with concerned parties for the return of 30,000 grabbed acres in Olorien.

He had advocated tirelessly on the floor of the House for the integrity of district boundaries so that KMC, the Export Processing Zone and EAPCC would be compelled to pay taxes to Olkejuado County Council.

Whenever he went to EAPCC to seek jobs for his constituents, some of the staff felt bullied by General’s towering height, his demands and his gruff no-compromise manner. He always left with what he wanted, including an annual bursary. However, some of those he got employed there worked with an attitude of entitlement and that dimmed General’s image even further.

As the 2007 General Election neared, Uhuru pulled out of the Orange pact and took with him most of Kanu.

They ultimately supported Kibaki, who announced, on September 16, that he would defend his seat under a new coalition, the Party of National Unity (PNU).

Mugambi Imanyara registered the name Orange Democratic Movement before anyone else could. The remaining members had to register themselves under the name Orange Democratic Movement - Kenya.

Shortly thereafter, there was an internal dispute. Kalonzo Musyoka remained in charge of ODM-K.

Raila defected to the ODM party registered by Imanyara, taking with him Musalia Mudavadi, William Ruto, Joe Nyagah and Najib Balala.

As these party realignments played out, General happily remained in Kanu. I remember he had travelled to Seoul, South Korea, on official duty when he returned to find that the ground in Kajiado had shifted.

A delegation of close to 300 constituents called him to a meeting at Bomas and issued him with an ultimatum. He told me later that he stepped out of the meeting to call his party leader, Uhuru.

“Things are bad here,” General explained. “The community has come. I have been given an ultimatum that I either go to ODM or I lose the seat.” Uhuru yielded, “If it is your people who have spoken, just follow.”

Throughout his political career political parties didn’t really matter to General. It was the people who mattered, and what you do for them.

Tomorrow: Appointment to Cabinet and the pitfalls that came with the docket; his last day.

Also Read the first instalment: Day a furious Kenyatta blasted Gen Nkaissery at State House

Also Read the second instalment: The tense phone call that reassured me of Nkaissery's love for me

Also Read the third instalment: The General and I: Day grave seller sent me on a frenzied drive across America

©Helen Nkaisserry / Santuri Media, 2022