From Ggabo and Ouattara to Ramaphosa and Zuma, the incumbent-predecessor love-hate relationship is not unique on the continent

Ivory Coast President Alassane Ouattara (right) and his predecessor and former rival Laurent Gbagbo (left) address a press conference at the presidential palace in Abidjan, on July 27, 2021 following their first talks since Gbagbo returned from Europe after a nearly 10-year absence.

The culture of antagonism between former presidents and their successors is nothing new on the continent, a situation that has left political analysts and commentators asking whether the current Kenyan head of state is following suit.

None other than Deputy President Rigathi Gachagua has on many occasions claimed that “some people are lucky that our President is a forgiving man who wishes us to forget the mess of our predecessors”

“We are finding it difficult to just forgive and move on,” he has been quoted as saying.

Historian and political analyst, Macharia Munene, says Africa needs mature democratisation.

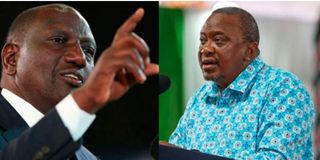

President William Ruto (left) and his predecessor Uhuru Kenyatta.

Prof Munene says democracy in Africa should build strong institutions that can pursue justice without fear or favour, regardless of who is involved.

“We are tuned to the absurdity that one of the core public service agenda for the incoming president is to protect the predecessors but in exchange of them (predecessors) keeping out of politics…not like in United States where former President Donald Trump is taken to court and no such absurd pronouncements of revenge or witch-hunting emanate from their supporters,” he said.

Former Cote d’Ivoire president Laurent Gbagbo found himself in trouble when his successor Alassane Ouattara shipped him to the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague, Netherlands, in November 2011.

This followed violence that rocked the country after the 2010 presidential election that left at least 3, 000 people dead and thousands others injured and displaced.

Mr Gbagbo was also convicted for corruption-related charges in 2019 and faces a 20-year prison sentence.

But facing an election in 2025 where he might seek a fourth term, Ouattara has started mending fences with his predecessor, starting by pardoning him in the corruption case.

In this handout photograph released by the South African Government Communication and Information System (GCIS) on February 20, 2018, South Africa's President Cyril Ramaphosa (right) shakes hands with his predecessor Jacob Zuma at a farewell cocktail function for President Zuma at The Presidency, Tuynhuys, Cape Town.

After being acquitted by the ICC in 2019, Mr Gbagbo appears to be marshalling forces to influence the 2025 elections to go against Ouattara should the latter contest.

Botswana in southern Africa is another theatre of conflict.

Immediate former President Ian Khama has vowed to make his successor Mokgweetsi Masisi a one term leader.

Mr Khama has on numerous occasions been quoted as saying that one of his biggest mistakes was to let his deputy succeed him in 2018.

Also read: Stable Botswana to vote in rare cliffhanger

In a language similar to the one being used in Kenya against President Ruto, Mr Khama once said: “This is a regime driven by greed, corruption and self-interests that undermine democracy”.

He has vowed to have Mr Masisi kicked out in next year’s elections, the very same pronouncements Mr Uhuru Kenyatta’s remaining allies are saying of the incumbent who faces the electorate one more time in 2027.

In Zambia, President Hakainde Hichilema is at war with his predecessor Edgar Lungu, whom he accuses of running state capture during his tenure.

Mr Lungu’s wife, Esther, son and daughter have since been questioned over corruption allegations.

Since August 2021, when he lost power and handed over to Mr Hichilema, the former president has been accusing his predecessor of “running an administration of systematically peeling an onion where they target my family members so as to reach me”.

In South Africa, President Cyril Ramaphosa has been unrelenting in ensuring government institutions hold his predecessor Jacob Zuma to account over widespread corruption allegations generally referred to as state capture.

President Ruto had set for himself a target of investigating state capture against Mr Kenyatta in his 100 first days in office.

He peculiarly dropped the decision, citing “fluidity”.

Mr Ramaphosa’s relationship with Mr Zuma as deputy and boss followed the same script as was that of Mr Kenyatta and Dr Ruto of fallout but remaining stuck together to the ballot.

They picked their quarrels after the handover.