Developing story: Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi confirmed dead in chopper crash

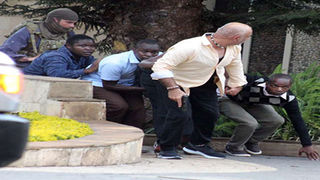

Christian Craighead (left, in a balaclava) escorts people to safety during the rescue operation at DusitD2 Hotel in Nairobi on January 15, 2019.

| File | Nation Media GroupNews

Premium

How the UK blew the Dusit terrorist attack memoirs

Had the UK government allowed the publication of a book on the DusitD2 hotel complex terrorist attack in Nairobi, we would have known the inner workings of a special unit that operates in Kenya and how they were involved in the operation.

The High Court in London has now told “Christian Craighead” – who uses that pseudonym – to forget about the memoirs.

During the Dusit incident, which involved an al-Shabaab terrorist attack in Nairobi in which about 21 people were killed on January 15, 2019, Craighead was one of the stars.

He wore a balaclava, was photographed escorting people out of the building, and featured prominently in Western publications.

It now appears that he was conscious that he was creating an identity of himself as a superhero to enable him to sell the book.

British High Court has told him to forget the memoirs for allowing publication would endanger others. Craighead was shattered.

The inside story of DusitD2 was about to die. He was summoned with his literary agent and publisher and told that sharing the manuscript was a breach of contract.

He had already sold the rights to his book in return for an advance sum of £160,000 plus royalties and newspaper serialisation fees. He had also received an advance of £40,000.

The Ministry of Defence said they were not opposed to Craighead writing memoirs on his upbringing and life outside the army and joining UK Special Forces.

“But he was not authorised to publish any other information in his possession by virtual of his former membership of UKSF.”

While the book had 32 chapters and the draft was 249 pages long, Craighead was asked to remove the prologue, delete 23 chapters in whole, most of the two other chapters, and delete several names and sentences in the remainder.

Without those chapters, the book was gone. It was not supposed to go that way. Craighead had at first talked to a “close friend” identified as Soldier C, who was working in the Disclosure Cell, about his intention to write a book.

Soldier C appeared to have made Craighead believe he would permit him to publish the memoir. In essence, Craighead was hoping that friendship would help him navigate a confidentiality clause he had signed.

Riverside complex in Nairobi.

“If the manuscript is finished, then please send it over. Once I have checked it over and MoD are happy then I will grant you EPAW (express prior authority in writing) which is your permission to go to print,” he had been promised.

Soldier C kept on promising that all was well. “If I don’t pick anything major up I will hopefully get your EPAW letter by Friday,” he was told in one of the promises. But when Soldier C realised that the book would not be approved, he reallocated the request (from the publisher) to Soldier D.

Soldier D introduced himself to the publisher by email on January 29, 2021, and on the same day, the (then) Chief of the General Staff, General Sir Mark Carleton-Smith, informed Craighead’s literary agent that “in its current form the book will not be authorised”, and that the Disclosure Cell “feel they have covered the ground with (the publisher) as to which elements need redaction”.

UKSF officials found that the Dusit book would have compromised state security and that Special Forces should go on duty with a book contract in mind.

“(The) memoir demonstrates that he was conscious during the operation of the press interest. In my view, … the possibility of writing a book about an operation may cloud the judgement of some (group members) and cause others to doubt (even if only momentarily) the motivation of their comrades,” Justice Steyn said this month.

The import of this case is that it will reverberate within our courts, for it has shown the limitations of freedom of expression. More so, it was supposed to test the place of the Official Secrets Act and confidentiality contracts that employees normally sign.

The case is important because it touches on the right to publish insider information if you have signed non-disclosure clauses.

We know from the case, which concluded this month that Craighead was a former United Kingdom Special Forces (UKSF) member involved in the Dusit incident. It is also the first case in which a public law challenge to a refusal of authorisation has moved to a substantive hearing, according to Justice Steyn.

In the UK, members of MI4, MI6, and GCHQ (Government Communications Headquarters) are exempted from invoking the freedom of information clause. It all started when the Secretary of state refused on July 25, 2022, to permit Craighead to publish a memoir he had written recounting his involvement in the terrorist attack of January 2019.

Craighead had joined the special forces on October 4, 1996, and was asked to sign a confidentiality clause saying he “will not disclose without express prior authority from MOD any information, document or other article relating to the work of (UKSF) which has been in my possession by virtue of my position as a member…”

Kenya forensic officials with the help of US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) officials collect evidence from a vehicle believed to have been used by the terrorists before they attacked DusitD2 complex on Riverside Drive in Nairobi on January 17, 2019.

Spill the beans

The Dusit incident gave Craighead some accolades, and he was awarded the Conspicuous Gallantry Cross. But if Craighead thought that the Secretary of State would allow him to spill the beans on the British operation in Kenya, he was shocked. He refused to give the ‘express prior authority in writing’.

Craighead fought back and went to court arguing that, that was unlawful interference with his right to freedom of expression as per Article 10 of the European Convention of Human Rights, and that the decision was “irrational.”

It was a very secret case. We might never know the content of the confidential documents that were tabled by the Secretary of State as evidence for they were all put “within a confidential ring.” Much of the case was heard in private, meaning the public and the press were kept out. Again., the UKSF operates covertly and in extremely dangerous environments.

So secretive is their work that successive UK governments have adopted the NCND policy, which means ‘neither confirm nor deny.’ Asking the Court to stop the book, the Director of Special Forces said: “I do not want my personnel wondering in a critical moment whether they might later be accused of dithering or being too gung ho, whether such- and-such a step might lead to a book deal or whether someone alongside them might be a weak link with an eye for the main chance.”

Details of the case are that Craighead had signed a confidentiality contract in which he agreed that, unless he obtained “express prior authority in writing’ first, he would not disclose any information about the work of UKSF or statement which purports to be such a disclosure. The Secretary of State argued that the material in the book would “cause damage to national security”.

The court was forced to weigh the circumstances in which the Court can hear the matter privately by balancing the need of the public to know and the harm to the national interest. The Judge then adopted an open judgment.

The court was told that the memoir contains a “significant quantity of sensitive information”.

Interestingly, Chris Ryan has published the Dusit D2 story, a fictionalised version of Craighead’s story. It was released last year as a novel, Outcast.

Mayli Chapman has also written a memoir of Dusit titled “Terrorist Attack Girl: How I survived Terrorism and reconstructed my shattered mind.”

In his ruling, the Judge said that although the right to freedom of expression, which includes the right to impart information and to receive it, is one of the essential foundations of a democratic society… Here is a real and significant risk of publication of the memoir leading to public controversy which would be damaging to the morale of UKSF”.

The Judge appeared to place community interest above personal interest and defined the former as entailing: “protection of lives, the protection of national security, the maintenance of the morale and efficiency ... the interests of the community substantially outweigh the claimant’s interest in publishing a memoir about the Dusit Incident.

“In my view, despite the extensive media (and social media) coverage of the Dusit Incident (including photographs, commentary and analysis by third parties of Mr Craighead’s role, actions, clothing and equipment), the contents of the memoir are such that they cannot be said to be generally accessible,” said the Judge. And with that, we got another case that shows that public interests will override private interests.

[email protected] @johnkamau1