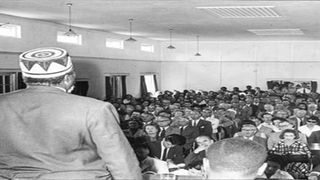

Mzee Jomo Kenyatta addresses settlers in Nakuru in 1963. British settlers were opposed to the creation of a Jewish state.

| FileNews

Premium

How charging elephants, lions and Maasai warriors thwarted a proposed Jewish state in Uasin Gishu

There were two nights of terror. Adrenaline was high. A Zionist delegation sent to fact-find the suitability of Uasin Gishu as a Jewish state encountered three life-threatening encounters that made them reject the British offer.

As Israel continues its war with Palestine, how a Jewish colony was almost established in Kenya 120 years ago has been forgotten.

It is recorded that as the fact-finding mission visited Londiani, a herd of elephants invaded the tents of the terrified Jews.

The following day, they were visited by lions, which started sniffing at the tents. It was a bad omen. Had colonial settler Ewart Grogan – who had a timber concession within Mau Forest – not been around some Maasai warriors would have killed the group. Grogans claims credit for asking the Maasai to leave.

Back in Nairobi, the Zionist commission reported that they had seen an “unholy land”, and the British offer to turn parts of its east African protectorate into a Jewish state collapsed.

But that is just part of the story of the forgotten attempts to create a Jewish state in Kenya.

If the State was created, Israel would not exist in its modern cartographical form – and perhaps, the ongoing war with Palestine would have been evaded.

Against the advice of colonial governor Sir Charles Eliot, the British Foreign Office had insisted that a Zionist colony should be started within Uasin Gishu by pushing the local communities to give space.

That was the idea of Joseph Chamberlain, the British Secretary of State for the Colonies, whose intent would have jeopardised the creation of a British colony.

The East African Jewish State was tied to the railway, the lunatic express, which was not making money.

According to railway historian M.F Hill, in his book Permanent Way, “the Foreign Office and the Treasury were depressed by the apparent millstone which the building of the Uganda Railway had shackled to the British taxpayer”, they wanted settlement schemes to be established to make the railway pay.

But who was to be settled? The Foreign Office “believed that settlement could be more quickly achieved if the future settlers were of other [races] than British stock”.

At first, the Colonial Office had considered creating Indian settlements, but the idea was discarded. The Foreign Office also considered settling Finns in the Kenya highlands and sent a letter to Governor Elliot, who was apprehensive. He thought that the Mau would not be hospitable to the Finns.

Unbeknown to London, Elliot favoured a pure British colony. After the idea of a Finn settlement was dropped, the idea of settling the Jewish refugees from Russia and Poland was floated by Chamberlain, and the Foreign Office took it with gusto.

Chamberlain visited East Africa in 1902 after persecuted Russian Jews renewed their political efforts to find a national home in Palestine. But a scouting mission sent to the Sinai Peninsula found the place harsher than it was presented in the Bible.

They reported that the “desert (was) more hopeless than it was when (our) ancestors wandered and murmured there, a desolation of stone, sand and salt”. As a result, they dismissed Sinai as a potential settlement.

As Chamberlain traveled from Mombasa to the highlands, the plight of the persecuted Jews was top of his mind. “He was impressed by the climate, by the look of the land, and by its lack of people,” wrote colonial historian M.F. Hills.

“Here, he thought, was the place for the oppressed Jews from the ghettos of Russia and Poland.” In the office, Chamberlain proposed setting aside 13,000 square-kilometers to settle the Jewish settlers. It was to be a semi-autonomous state with self-government and under a Jewish governor. It was to be protected by Great Britain.

The reaction was instantaneous. The proposal was sent to Theodor Herzl’s Zionist Congress, a symbolic Parliament in Basle, which voted 594 to 177 to accept the offer. By then, Dr Herzl was regarded as the father of Zionism.

Those who opposed the East African proposal at the Congress argued that it meant forfeiture of their bid to create a national home in Palestine – then a British colony. But Dr Herzl convinced the Jews that the search in Palestine for a single state might take time and that the East African offer was the best.

The Uasin Gishu proposal split the Jews into two: The East African Jews and the “true Zionist”. Herzl’s organisation collected money to finance a fact-finding expedition to East Africa. But before they left, Herzl died.

British settlers were also opposed to the creation of a Jewish state. The Commissioner said if the state was to be established, it should be in Uasin Gishu and Trans Nzoia considered by the settlers as “uninhabited”.

However, this was opposed by the British settlers, who held a mass meeting in Nairobi to protest the creation of a Jewish state. In his letter to Lord Delamere, the chairman of the anti-Semitic movement in Nairobi, Governor Sir Charles Elliot wrote: “I am not anti-Semitic myself and do not share your objections to Indians and other non-English settlers, but I confess that as far as I understand the present proposal, I view it with very mixed feelings.”

Sir Charles worried that if Britain cut aid to the settlers, the entire settler colony might collapse. He suggested that the only way to defeat the Jewish state proposal was to increase the number of British settlers in Kenya.

Elliot was apprehensive about a Jewish settlement in what was then British East Africa since they were poor farmers. He argued that though wealthy Jews were wealthy, the poor Jews were destitute.

The targeted Jews from Russia and Poland were poor and lived in squalor. But rather than implement a scheme he was uncomfortable with; he resigned and left the country. That was when the Jewish Commission was sent to Nairobi accompanied by officials of the Foreign Office.

Attending the group were two settlers Ewart Grogan and Edward Lingham. Grogan would later describe the Jewish delegation as “scholarly types, but not farmers or settler-pioneer types”.

When Grogan mentioned this to the head of the delegation, he was assured that those who would be brought to settle were “poor artisans”.

Grogan wondered why the British government would bring in a class of artisans when they had Indians playing that role. In the Rift Valley, the group was taken to Londiani and parts of Mau escarpment, where they encountered the lions and the elephants. It was a hot day and not impressive.

“On the second day, the Commissioners met a band of Maasai warriors, strangely far from their usual haunts. The Maasai were arrayed in full regalia of war. They surrounded the Commissioner’s party and made a great display of warlike threat and cry,” wrote Hill. Besides the threat of the Maasai, the lions and elephants threatened to overrun the camp.

“The Commissioners had seen enough of this wild land.”

The group returned to Nairobi and London and made their final report, and they dismissed Uasin Gishu as “unsuited to the needs of Jewish refugees from Russia and Poland”.

In August 1905, the Zionist Congress endorsed the report, and the dream of a Zionist state in Kenya ended there. It was a triumph for the true Zionists who opposed the halfway house to Zion.

Britain would later help to create the Jewish State within Palestine in 1948. This land has become the most contested.

Had the lions and the elephants not visited the camp, and had the Maasai not disrupted the party with threats, there could have emerged a Jewish state within Kenya. Kenya’s history would, perhaps, be different.

[email protected] @johnkamau1