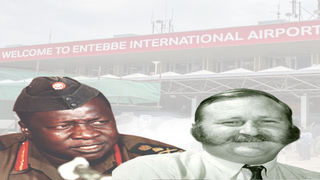

Former Ugandan dictator Idi Amin Dada (left) and Bruce McKenzie who was Kenya’s Agriculture Minister in the 1970s.

| FileNews

Premium

David Silverstein: Day I attempted to call Idi Amin to end Entebbe hostage crisis

What you need to know:

- This is the second instalment of a five-part serialisation of ‘Heartbeat: An American Cardiologist in Kenya’ by Dr David Silverstein. Read the first part here: Why two doctors were detained after Kenyatta death

- In this second instalment, Dr David Silverstein reveals how he attempted to get the intervention of Ugandan dictator Idi Amin’s personal doctor during the Entebbe hostage crisis, untold details of Kenya’s role in the dramatic operation and his experience treating the rescued captives at Nairobi Hospital.

On Sunday, June 27, 1976, Air France flight 139 took off from Israel’s Ben Gurion Airport, known for its notoriously tight security checks.

Its next stopover was Athens where security had a reputation for being lax. Among the passengers were three men and a woman carrying large black bags that held pistols, hand grenades and a sub-machine gun.

Two were members of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine.

Two belonged to a little-known group called Revolutionary Cells. Within the week, its name would be broadcast around the world, the prelude to gaining a reputation as one of West Germany’s most dangerous left-wing organisations.

On that sunny summer’s day, the four were driven by a common agenda – anti-Zionism.

The Airbus A300 lifted into the skies and, as the seatbelt sign switched off, the four terrorists burst into the aisles shouting and threatening the startled passengers.

Two ran to the cockpit to instruct the pilots to change course and head for Libya. The hijacked plane refuelled in Benghazi and took off again. Its destination was Entebbe on the shores of Lake Victoria in Uganda.

On the Monday afternoon of June 28, when the Air France pilot called the Entebbe control tower, he was answered by a voice in Arabic.

Three PLO terrorists were already at the airport to welcome their colleagues. They wanted the release of 53 Palestinian and pro-Palestinian militants. Forty were being held in Israel.

The others were in prisons in France, Germany, Switzerland and Kenya. They were also asking a $5 million ransom for the release of the plane. If these demands were not met, they would start killing the hostages on Thursday, July 1.

It was a daunting situation for the Israelis. From the moment they had learned of the hijacking, they had determined the hostages must be rescued. But how to do that? There were 254 on the plane and nearly half of them were Jews, the majority of them Israelis.

Entebbe was more than 2,000 miles from Israel. The Israelis would have to overfly hostile countries like Egypt, Sudan and Somalia and risk being shot down before they had even reached their target.

The planes could fuel at Sharm-el-Sheikh in the Sinai Peninsula during the approach, but they would have to refuel again somewhere else to make the return journey.

Israel was boycotted by the Organisation of African Unity. It was doubtful any African country would allow the Israeli military to land on its soil.

There was an additional, unprecedented problem. Idi Amin, Uganda’s mercurial and brutal head of state and the chairman of the OAU, was hosting the terrorists. He had been privy to the hijackers’ plans and had promised not only to welcome them but to provide military protection.

Amphibious attack

With only two days before the deadline, time was of the essence as the Israeli government grappled with the impossible choice it faced.

PM Yitzhak Rabin wanted to save lives by giving in to the hijackers’ demands. Defence minister Shimon Peres argued that a rescue mission had to be mounted to discourage similar attacks. The hours ticked by without a decision.

In the departure lounge at Entebbe on the night of Wednesday, June 30, the German hijackers separated Jews from the other passengers, invoking chilling memories of the Holocaust. The deadline for shooting passengers if demands were not met was only hours away.

The 12-strong Air France crew refused to abandon the remaining passengers. The Jewish hostages were 106.

Less than two hours before the 2pm deadline on Thursday, July 1, the Cabinet voted unanimously to begin negotiating the release of Palestinian prisoners in exchange for the hostages on the condition that the deadline be extended to July 4. Amin agreed.

While the pros and cons of military intervention continued to be argued back and forth, military and intelligence chiefs were pressing ahead with preparations for a raid on Entebbe. The freed passengers had been flown to Paris.

Mossad agents interviewed them as soon as their plane touched down. This gave them sufficient information to build an accurate picture of where the hostages were being held in the airport terminal and the number of terrorists guarding them.

Also Read: Hero French pilot in Entebbe hijack dies

Intelligence suggested that hundreds of Ugandan soldiers were guarding the airport. Whatever the exact strength of the military and where they were positioned was impossible to ascertain, but one thing was clear – the element of surprise would be crucial.

The rescue mission was of a complexity. It called for exceptional courage and ingenuity. It had not received government approval. There was a strong possibility that it would be a failure. It was given a name inspired by James Bond – “Operation Thunderbolt”.

How to reach the terminal without being detected and then extract everyone safely was distilled down to four options.

One plan entailed flying into Entebbe in an Air Force plane carrying soldiers disguised as the prisoners whose release had been demanded. They would land, rush to the terminal and extricate the hostages.

As the airport was only one kilometre from Lake Victoria, two other plans were based on an amphibious attack. A team of Navy Seals and commandos would parachute onto the lake with boats, sail to shore and rush to the terminal.

Alternatively, the same force would fly to Nairobi and cross the vast lake to Entebbe in a yacht pre-positioned by a Mossad agent. The three plans had drawbacks, not least the crocodiles that would have snapped up anyone who might fall overboard.

The fourth plan at first seemed to be the most impractical of all, but it was the one that was chosen. Four Hercules C-130 transport planes would fly 100 soldiers to Entebbe and land in the dark. The lead team of 29 commandos would approach the terminal in a Mercedes Benz rebuilt as a replica of the presidential Mercedes that Amin travelled in.

It would be accompanied by two Land Rovers. It was hoped the simulated motorcade would not arouse suspicion and thus be able to bypass security checkpoints without being stopped.

It was crucial to maintain the element of surprise as the men in the motorcade rushed the terminal and extricated everyone. The other 70 soldiers would secure the perimeters and fend off the Ugandan troops believed to be out there in every direction.

The idea was plausible. Amin had visited the hostages more than once so another visit would not be considered unusual.

He claimed he had been sent by God and had provided them with mattresses and food. He was at his charming best when playing the Big Man. He even received a standing ovation on one visit.

Back in Israel that Thursday, July 1, a clapped-out white Mercedes was located in the back streets of Tel Aviv while elsewhere, a tailor ran up imitation Ugandan army uniforms.

A civilian mechanic worked through the night to rebuild the Mercedes and paint it black. Someone else forged a Ugandan number plate. At the same time, aeroplanes, vehicles and artillery were being organised.

The medical team that would be on hand to treat injuries needed to secure a large supply of blood in case there were heavy casualties.

So as not to alert the media, they created a cover story that a crisis was emerging on the northern border with Lebanon. There was even a supply of empty milk cans for the transport planes in case the hostages vomited. Everything was being thought through down to the last detail.

These preparations were being undertaken in top secrecy. The world looked on in ignorance of what was taking place behind the scenes.

Once again, dread and anxiety gripped Jewish and non-Jewish friends of Israel. Nairobi was no exception. Saul Gordon, a fellow member of our tight-knit Jewish community, was beside himself with worry.

I was distraught about it too and willing to do anything to help. Saul owned a travel business with his brother and was a Zionist. He was also excitable. Desperate to do something, anything, to help the hostages, he called me several times to discuss bribing Amin. Did I know how to get in touch with him?

As it happened, I was acquainted with Amin’s physician. He was a fellow cardiologist called Paul D’Arbela. It seemed to me to be a Hail Mary pass, but I diligently tried and failed to get hold of D’Arbela.

Also Read: Mossad, McKenzie, Idi Amin: The strange mix

Meanwhile, crucial cooperation was being provided from other quarters. Without it, the rescue could never have succeeded.

Charles Njonjo, at that time the attorney general, has recalled the story to me many times. Njonjo received a visit from Eli Engel, the Mossad chief in Kenya. Engel wished to discuss Kenyan participation in the raid. It was a sensitive situation. Kenya, along with the rest of Africa, had severed ties with Israel in the aftermath of the 1973 war. Nevertheless, Njonjo was a supporter of Israel, and welcomed Engel and two other Mossad agents onto the outdoor terrace of his home.

The Mossad chief unfolded maps and spread them out on the glass top of a wrought-iron table on the verandah. The men bent over them, heads almost touching, as Engel traced the route the rescue team intended to take.

They were so engrossed, they barely noticed when Njonjo’s wife Margaret appeared with coffee. The task force would land in Sharm el-Sheikh, Sinai, to refuel. From there, the planes would follow the international flight path along the Red Sea, flying at 30 meters to avoid radar detection by Egyptians, Jordanians and Saudis.

The planes would circumvent Djibouti and continue west over Somaliland and Ethiopia’s Ogaden region. Engel’s stubby finger paused a second for effect and then crossed into Kenyan airspace and headed west over the Rift Valley until it reached Lake Victoria and came to rest on Entebbe.

Ex Ugandan Dictator Idi Amin Dada. He died in 2003 while in exile

Not only did Israel need Kenya to look the other way, Engel told Njonjo, the pilots wanted to refuel the planes in Nairobi on the way home. Njonjo was silent.

The minutes ticked by as he thought everything through, considering the implications if anything went wrong on Kenyan soil. He nodded at Engel: “If Mzee agrees, I’ll see to it.”

Njonjo called President Jomo Kenyatta at his Gatundu home and carefully explained everything. The president hesitated a moment then said: “Do what you see fit, Njonjo. But I warn you, you’re on your own. I have no knowledge of this matter if it leaks out.”

Three other Kenyans knew about the raid in advance. Njonjo notified Ben Gethi, head of the General Service Unit, and Kenya’s spymaster, James Kanyotu, who headed Special Branch. The third person was Njonjo’s close friend and business partner, Bruce McKenzie, the South Africa-born Kenyan Minister for Agriculture, who had links to Mossad and Britain’s MI6.

Right-hand drive

Thanks to McKenzie, another important part of the operation was executed. The most recent aerial photos of the airport that Mossad could provide were five years old.

The Israelis needed up-to-date images of the air terminal or the success of the operation would be at risk. A pilot who was a Mossad operative flew to Kenya from London.

With McKenzie’s help, he hired a small plane at Nairobi’s Wilson Airport and filed a flight plan for Entebbe. When he got there, he informed the control tower he had a technical malfunction with the landing gear and was going to circle the airport several times while he fixed it.

After thoroughly photographing the ground layout, he spoke to the control tower again. He had been unable to fix the problem and so was returning to Nairobi.

By a stroke of luck, the Entebbe airport had been built by an Israeli company, Solel Boneh, and the blueprints were accessible in Israel.

The night of Friday, July 2, with the new deadline only two days away, the army built a partial replica of the terminal where the hostages were held.

They did mock assaults on the building for the rest of the night and practised loading and unloading the C-130s with men, vehicles and equipment to make sure the rescue could be executed as smoothly as possible. On Saturday afternoon July 3, the Mossad photos of Entebbe airport were delivered to the Air Force base near Lod. With these in hand, the planes took off even though the Cabinet still had not given the rescue mission permission to go ahead.

The lead C-130 carried men from Sayeret Metkal, the Israeli Defence Forces’ elite unit charged with counter-terrorism operations and hostage rescue.

It was modelled on Britain’s SAS. Delta Force was its American counterpart. Its cool-headed commander was Lt Col Yonatan Netanyahu, the elder brother of Benjamin Netanyahu, who later became Israel’s longest serving prime minister.

These were the men designated to disembark in the bogus Amin motorcade, enter the terminal, subdue the terrorists and extract the hostages.

The other three C-130s were carrying support troops and armoured cars. Trailing some way behind were two Boeing 707s.

One was the command centre for several generals and senior officers. It would remain airborne, circling overhead for the duration of the operation.

The other contained a field hospital for treating the wounded. Not long after taking off, the fleet touched down in the Sinai to top up fuel tanks. It was only then that the generals received word that Rabin had sanctioned Operation Thunderbolt.

In the early hours of Sunday, July 4, the planes landed at Entebbe under cover of darkness. The Mercedes Benz rolled down the ramp with Netanyahu in the front passenger seat. As the motorcade approached the terminal, two soldiers stepped forward with raised rifles. They were shot dead instantly, one with a silencer and one with an automatic machine gun.

It was discovered in the aftermath that Amin had recently exchanged his black Mercedes for a white one. Many years later, the Israelis learned that Ugandan cars are right-hand drive, unlike the left-hand drive Mercedes in Tel Aviv.

Unfortunately, the sound of the second shot stole the element of surprise. Netanyahu had been badly hurt in the crossfire, but there was no time to stop and tend to his injuries. The commandos stormed the departures lounge where the hostages were being held, shouting at everyone to lie down.

In the confusion and noise, two hostages were shot dead by the hijackers. A third hostage stood up and was immediately shot by a commando who had mistaken him for a terrorist. Within minutes, all the hijackers were dead.

Outside there was intense shooting from all sides for another 15 minutes as the support troops fought off the Ugandans, killing 20. The commandos also destroyed five MiG-21 fighter jets and three MiG-17s that were on the tarmac.

They didn’t want anyone scrambling a jet and chasing after them. A child confused the noise and light of the explosions and tracers for fireworks and shouted, ‘Wow! How beautiful!’

The efficient military operation now descended into temporary chaos as the commandos tried to herd the hostages into the waiting planes. Several people were dragging their luggage behind them.

One passenger insisted on returning to the terminal to reclaim his duty-free purchases. An Air France flight attendant had been slightly wounded by a ricocheting bullet. She was clad only in her red underwear as she had been asleep. One of the soldiers threw her over his shoulder and raced for the plane with bullets whizzing past his head.

The last C-130 lifted off an hour and 39 minutes after the first plane had landed at Entebbe.

The mood in the C-130s was subdued. Everyone was relieved and thankful to be alive and safe. But they were too exhausted and traumatised to celebrate. Added to this was the sadness of Yonatan Netanhayu’s death. He had lost a large amount of blood. Despite every effort, doctors were unable to save him. He passed away during the flight to Nairobi.

Former Agriculture minister Bruce McKenzie.

Njonjo was true to his word. He had organised Kenyan soldiers to guard the planes while they were being refuelled. Three hostages who had been wounded were offloaded and taken to Nairobi Hospital, accompanied by two Israeli doctors.

One of them was Pasco Cohen, the hostage who had been accidentally shot by a commando. Tom Jorgensen, the surgeon on call, invited the Israelis to join him performing surgery on Cohen. They declined to scrub in, telling Jorgensen they trusted him to do a good job.

Unfortunately, Cohen couldn’t be saved. He died on the operating table. In those days, I was still attached to Kenyatta National Hospital, but as the only cardiologist in the country, I was sometimes asked to look after patients at Nairobi Hospital.

I didn’t want to tread on anyone’s toes, so I developed the practice of seeing my patients very early in the morning and late at night to avoid bumping into the other doctors. I happened to be making my rounds when the Israelis were admitted.

I had no idea what was going on until Tom explained. Since I was a Jew who spoke Hebrew, he asked me to attend to an Israeli casualty who had been wounded in the left shoulder. I administered the appropriate antibiotics and analgesics and took the man’s history in Hebrew.

Also at the hospital that night were members of the Nairobi Jewish community. Among them was Vaizman Aharoni, a civil engineer and a family friend. They arrived with their side arms to protect the wounded if necessary.

That weekend, Njonjo and Margaret were in Laikipia, staying with their friend Court Parfet, the American conservationist. Margaret first heard about the Entebbe rescue listening to the BBC on her shortwave radio at Parfet’s Solio Ranch. She rushed to tell Njonjo the exciting news and was perplexed by his low-key reaction.

I, on the other hand, was in a state of high excitement. I can’t recall ever being that wound up. I had the same choked up feelings as when the shofar was blown at Old Jerusalem’s Western Wall during the Six Day War in 1967.

My phone rang all day, with calls of concern from my friends and family in the US. Many of the staff at Kenyatta National Hospital also called, thinking that I must have been involved. They didn’t differentiate between being Jewish and being Israeli. Some asked: “‘What was it like at Entebbe?”

Amin, of course, saw matters in a different light. Humiliated by the apparent ease with which the Israelis had extracted the hostages, he exacted bloody revenge. The following week, some 245 Kenyans living in Uganda were killed.

Another 3,000 fled the country. Some of the Entebbe airport staff were murdered too, including Peter Kalanzi, the director of civil aviation, and Tobias Rugambi, who was in charge of air traffic services. Nails were driven into their skulls, then their bodies were pulverised beyond recognition with sledge hammers. Neither had been present during the raid.

Dora Bloch was the fourth hostage to die. She had choked on a piece of meat soon after arriving at Entebbe and had been taken to Mulago Hospital.

The day of the raid, she had been dragged from her bed and was last seen screaming as she was thrown into the back of a car. Her body was later found buried in a sugar plantation.

There was one more person who fell victim to Amin’s wrath – Bruce McKenzie. In May 1978, McKenzie and two colleagues flew to Entebbe in a light aircraft to discuss an arms deal with Amin. On their departure, Amin’s notorious British henchman, Bob Astles, presented them with a mounted lion’s head.

“It’s a gift from the Big Man,” he said and instructed the cargo handlers to stow it in the back of the plane. Concealed behind one of the animal’s glass eyes was a pressure-sensitive bomb designed to detonate when the plane descended below 3,000 metres.

As the plane flew over the Ngong Hills on its final approach to Wilson Airport, it exploded. The three men and their young pilot were killed instantly.

Tomorrow in the Daily Nation: Controversy over the death of Chief Justice Zacchaeus Chesoni and Dr David Silverstein’s fight to clear his name and save medical career