Kenneth Kaunda: Son of Malawian preacher who became Zambia's liberation hero

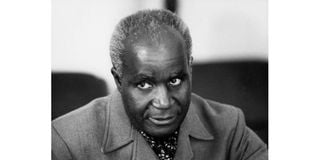

Former Zambian President Kenneth Kaunda. Zambia's first President has died aged 97 on June 17, 2021.

Lusaka

Kenneth Kaunda, Zambia’s founding president, was an indelible figure at the centre of Zambia's nation-building which spanned more than five decades. He had lived to a ripe old age, surviving many health scares and admissions in hospitals towards the end.

He always resurfaced more fit and would be seen afterwards jogging at national events whenever he was invited to the podium. He once told an interviewer that his diet was mostly vegetable and fruit salad as well as raw seeds and nuts.

KK, as he was fondly called, was a towering figure from his days as a liberation hero and was still revered by the 18 million Zambians he led to independence from Britain in 1964.

Although his presence in the public space had slowed down, mostly due to old age, several Zambians and other international citizens of repute would make it a point to visit his home east of the capital Lusaka where the former teacher settled after politics.

Immigrant preacher

The son of a Malawian immigrant preacher David Kaunda, who settled in northern Zambia in the early 1900s, President Kaunda was highly regarded by Zambians and still taken as one of their own, even when he suffered the humiliation of having been declared stateless by his successor, Frederick Chiluba.

Citizens protested the act as being outside the acceptable political manoeuvres.

Mr Chiluba had used a special clause in law, which barred people whose grandparents were not born in Zambia from becoming president. It is a law that cut Kaunda’s political legs, making him ineligible to contest again after he left office in 1991, ending Zambia’s 27 years of single-party rule, during which the country was run on socialist principles.

At several functions, he would be seen brandishing his famous white handkerchief, wearing his trademark Kaunda suits now worn around the continent.

The father of eight (two of his children died earlier) and a vegan of many years, is one of the last post-independence heroes in Africa to exit the stage. Nonetheless, he handed over power peacefully following defeat at the elections.

Still popular

He was still popular, but not exactly in a political sense. His critics argue that he ran the country under a restrictive set of economic policies, most of which were dismantled by Chiluba.

Born at the Lubwa Mission in Chinsali in Northern Rhodesia, today’s Zambia, he was the last-born in a family raised under the strict tenets of the Church of Scotland, where his father was a preacher.

At the apex of political tensions due to the one-party state policies, increasing autocracy, and the resultant economic downturn that led to shortage of food and other essential items in late 1989 and into 1990, it was clear the Kaunda government was headed for the exit. Those shortages of essential commodities bred food riots.

However, having been in power for 27 years, it was unimaginable Dr Kaunda would agree to leave office.

Pressure was mounting -- the labour movement, students, young and adults alike were fed up and were set to kick him out.

A group of concerned and mostly educated Zambians gathered at Lusaka’s Garden House Motel on July 19-20, 1990, where they formed the Movement for Multiparty Democracy (MMD), which later transformed into a political party after Dr Kaunda cut short his tenure, amended the constitution to end the one-party state and return to multiparty politics, and called for elections on October 31, 1991.

The MMD and Mr Chiluba emerged victorious, ending Dr Kaunda and his United National Independence Party (Unip)’s 27 year-reign.

Political freedoms

Soon after losing power, the tribulations started for Dr Kaunda: the state denied him a retirement house, froze his salary and other entitlements, and his political freedoms were regularly curtailed.

In a self-titled biography Levy Patrick Mwanawasa – An incentive for Prosperity, Zambia’s third President Levy Mwanawasa recounted to his biographer Amos Malupenga that:

“…I had to force him [Mr Chiluba] to give Kaunda his first salary [after leaving office]. …I said [to Chiluba], ‘you will also be a former president at some point and you would want to be properly treated’. That is when he gave me a cheque to go and give Kaunda. Dr Kaunda got his first cheque as an entitlement shortly before I resigned as Vice-President.”

“…soon after leaving State House, Dr Kenneth Kaunda was detained and searched on an allegation that he had stolen some books from State House … I advised that it was not necessary to resort to those levels … he was investigated and nothing came out of that investigation.”

But for his part, Mr Chiluba and his lieutenants on numerous occasions argued that he did not provide Dr Kaunda with his entitlements because the former president had returned to active politics against the provisions of the Constitution.

Amended the constitution

Dr Kaunda’s attempt to run for presidency again in 1996, five years after he left office, was thwarted when the Chiluba government amended the constitution – introducing stiffer conditions for one to qualify as a presidential candidate.

Amendment Act No. 18 of 1996 of the Zambian Constitution in Article 34(3)(b) stated: “A person shall be qualified to be a candidate for election as President if … both his parents are Zambians by birth or descent…”

This provision was widely considered to have been targeted at Dr Kaunda, who was well known to have been born of parents that originally came from the eastern neighbouring country – Malawi – and migrated to and settled in northern Zambia’s Chinsali District, where his father was a missionary.

Zambians and the international community widely condemned the Chiluba government for the repressive constitutional amendment.

Despite being technically stopped from running for presidency and withdrawal of his Unip party from the elections, Dr Kaunda marshalled political support as leader of the former governing party.

Political rally

Alongside another opposition leader and lawyer, Dr Rodger Chongwe, the former President was shot in August 1997, in the small mining town of Kabwe – about 140 kilometres north of Lusaka.

Dr Kaunda and Dr Chongwe claimed that state police shot and wounded them after they addressed a political rally.

A few months later, another misfortune befell Dr Kaunda. After the failed coup of October 1997, Dr Kaunda and many other opposition leaders were detained on suspicion that they were behind the army-staged coup attempt. The statesman denied any link to the coup.

In a bloody turn of events, Dr Kaunda’s son and widely anticipated heir of the leadership of his father’s party, Major Wezi Kaunda, was shot dead on November 4, 1999.

Political assassination

The Kaunda family, and Zambians in general, to date insist Major Kaunda, a former army officer, was killed in a political assassination.

Major Kaunda, once a Member of Parliament in the home village of his mother – former first lady Betty Kaunda – in Malambo Constituency in Eastern Province – was at the time of his assassination serving as chairman of Unip in Lusaka. The assassination was disguised as a carjacking.

His widow, who was with him in the vehicle when he arrived home in a Lusaka suburb, recounted that when the armed assassins approached them, her husband told his killers: “I am Major Wezi Kaunda. Please take my car, take whatever you want. I am not resisting. Spare my life and my wife. Just take the car.”

The gunmen reportedly retorted: “We know who you are. Do you think we don't know? Shoot him.”

They ordered him out of the vehicle and shot him multiple times. He was rushed to hospital but died a few hours later. The mystery of Major Kaunda’s assassination remains unsolved.

The killing of Major Kaunda escalated the tension between Dr Kaunda and Mr Chiluba. Dr Kaunda subsequently quit active politics in 2000. After his retirement, Dr Kaunda focused on peacemaking and mediation in Africa, as well as campaigns to combat HIV and Aids.

In recent years, he was seldom in public due to his advanced age. As an energetic young man, he played musical instruments and serenaded his wife Betty, who died a few years ago.

He also loved to write, and had published, among other books, Zambia Shall Be Free, an autobiography under Heinemann in 1962.