World Poetry Day: Celebrating the terrible beauty of the word

Poetry is, by rights and by tradition, “all the creative use of language”, whether spoken, recited, sung or written, to quote our illustrious ancestor, Okot p’Bitek.

A terrible beauty” is a paradoxical phrase, as the two main items in it appear to clash. We do not normally associate beauty with terribleness.

But that is how the Irish poet W. B. Yeats described a landmark event in the course of his country’s struggle against British colonialism. Yeats’s poem “Easter 1916” reflects on an anti-colonial demonstration in Dublin during which the English colonial troops shot to death a large number of Irish patriots.

Taking this massacre as marking an irreversible point in the liberation struggle, Yeats hails it as a remarkable game-changer in which everything is “changed utterly” and “a terrible beauty is born”.

In another reflection, Yeats wonders if another work of his, a short play about an Irish folk heroine, had led to protests in which still more people were killed. “Did that play of mine,” he wonders, “send out/Certain men that the English shot?”

This “terrible beauty” and power of words, especially poetic words, to inspire a struggle for utter or fundamental change, even in the face of great danger, is what was on my mind as we celebrated World Poetry Day on Tuesday this week, March 21st.

Those of us fully in the calling marked it mostly through sharing of our poetic products, both in print and in live performances. The most attention-catching event for me was in Kampala, where an eminent performance poet, Kagayi Ngobi, shared a stage with his mother, Mama Ruth Namusobya, in a live presentation of their compositions.

The majority of our people, however, either ignored the day or were left wondering what there was to celebrate about poetry, justifying a whole day of worldwide commemoration.

For a piece of recent history, World Poetry Day was officially established by UNESCO, the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation, in 1999. Its main purpose is “to promote the reading, writing, publishing and teaching of poetry throughout the world”, and to encourage the growth of national, regional and international poetry movements.

The celebration of poets and poetry, however, dates from very ancient times. In classical Greek times, for example, poetry and poetic drama were central parts of the celebration of the festivities of Dionysus, the deity of fertility and fruitfulness.

Remnants of the performances around these festivities, held in early spring (just about this time of the year) are what we treasure today as the classical Greek drama of Aeschylus, Euripides, Sophocles, Aristophanes and their contemporaries. There were also the great epic poets, like Homer of Greece and Virgil of Rome, who were greatly respected and publicly honoured in their communities.

The crucial question, however, is: why should poets and their works be held in high esteem? Why, specifically in our own times, should UNESCO want to promote the reading, writing, publishing and teaching of poetry?

These questions are not theoretical or academic in our societies. Many ignorant and misinformed leaders and policy-makers are actively demoting and downgrading the arts and humanities, including literature (read poetry), in our educational systems.

Literature dismissed

In their enthusiasm for so-called STEM-based education, some of these leaders have branded as “useless” disciplines like literature and philosophy.

They have gone even further, in some countries, and established discriminatory salary structures, seriously disadvantaging arts teachers while benefiting science teachers. A consistent and rational defence of the humanities in general and literature, in particular, is, thus, an existential necessity. We have to educate our leaders and policy-makers about the relevance and necessity of the humanities in a truly civilised society.

In the case of literature and poetry, we should use occasions like World Poetry Day to enlighten our societies about the true nature and working of poetry.

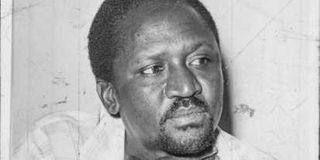

We can start by pointing out that “poetry” is much wider than the clipped, metred lines of verse that most of us associate with the activity. Poetry is, by rights and by tradition, “all the creative use of language”, whether spoken, recited, sung or written, to quote our illustrious ancestor, Okot p’Bitek.

Indeed, according to the ancient Greeks, whom we mentioned earlier, Poetry or Poetics is the whole discipline of producing, sharing and evaluating creative communication through language. An immortal text on this subject is Aristotle’s treatise, The Poetics.

By creative language, we mean communication in which the speaker or writer pays as much attention to the vehicle or medium of communication as to the content or message being conveyed.

"Moving language"

Poetry, and literature, have been variously described as “moving language”, “the best words in the best order”, language on the point of breaking into song or, simply, as the French novelist Gustave Flaubert puts it, the “inevitable” word.

The effect of such communication is that it touches the recipients (readers or listeners) simultaneously at several levels of their consciousness: physical, emotional, intellectual and spiritual.

It is only this kind of communication that can truly and effectively humanise our people. A good poem or play can better eradicate corruption, tribalism, promiscuity and violence from the hearts of our people than any number of algorithms or gigabytes that your superfast computer can produce.

Denying our people, especially the young, systematic and sustained access to this powerful poetic and literary skill will leave them exposed to the wiles and whims of political, religious and other opportunists and demagogues. These predators know, and fear, the power of literature. That is why they persecute, detain, exile and would even kill literary and other creative communicators and educators. Ask Ngugi wa Thiong’o.

Incidentally, do you realise that our best-known spiritual texts, the scriptures, are poetic? The Psalms, Proverbs and Song of Solomon in the Bible, for example, are explicit poems. The prophets, like Isiah, were poets (and were they persecuted!).

The Holy Qur’an, which has been described as a miracle of composition, is a poetic recitation. When it was first brought down to the Prophet (SAW), he was instructed to “recite” (iqra). That is where we get our own word “kukariri”, which we use for the recitation of our poems. Need I say more?

Ramadhan Kareem!

Prof Bukenya is a leading East African scholar of English and [email protected]