Why Taban lo Liyong is not about to write his last word

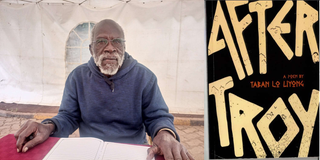

Prof Taban Lo Liyong at the United Kenya Club on November 31, 2022. Right: His book - after troy: a poem.

What you need to know:

- Title: after troy: a poem

- Author: Taban lo Liyong

- Publisher: Deep South

- Pages: 154

- Reviewer: Dorothy Kweyu

The book launch at United Kenya Club, off State House Road, Nairobi, seemed not to ruffle a decent crowd that had started gathering right on time, 5pm, testimony to the high regard in which octogenarian author Taban lo Liyong is held. There was a ‘mutado’ air to the delay seeing probably the next oldest person present was renowned publisher Henry Chakava. We, Africans, still revere age, hence neither the organiser, nor indeed Taban, offered any apology for lateness.

With more than 20 titles to his credit, there was every sign at the Monday event that, the author of The Last Word (1969) and Another Last Word (1990) is yet to utter his very last word, given his wit, mental clarity and alacrity.

At a time young people shun poetry as incomprehensible, Taban’s latest work reinforces his image of a maverick, not just because he is a poet, but more so because of after troy’s classical underpinnings. Not only that; save for the seven-page introduction by Rhodes University academic John Jackson and Taban’s 12-page afterword, the two-part poem is entirely in lower case, call it poetic licence. It’s a reminder of the old Nation House, where stories were type-written in lower case on A5 folios with sub-editors left to indicate the upper case and any missing punctuation before typesetting!

It’s amazing that the two third-year students of the University of Nairobi (UoN) could recite excerpts from the book so eloquently and in such a riveting manner that earned them not only the author’s nods of approbation, but of the entire audience. With such talent, there’s hope for the much-maligned subject of literature, which the current occupant of the House on the Hill has missed no opportunity to denigrate in favour of subjects that offer graduates job opportunities.

Indeed, the students’ powerful recital inspired the author to declare that his very last word might be a work of drama, and not poetry, which dominates his writings. These include Another Nigger Dead, Franz Fanon’s Uneven Ribs: with Poems More and More, Carrying Knowledge Up a Palm Tree and The Cows of Shambat, which is an anthology of Sudanese poems.

The young students’ recital from Taban’s book debunks the myth that is gaining currency among young Kenyans that money is everything and anything that doesn’t create instant wealth is to be shunned like the plague. The students and their Head of Department, Prof Miriam Musonye, together with her team, deserve accolades for making classical literature so accessible.

The passionate recital left no doubt that literature fires the imagination of its lovers, enriching the quality of the human person, which, in Kenya, is fast sinking into a depraved lust for money for its own sake, manifested in rank corruption.

Political analyst and publisher, Dr Barrack Muluka, rightly described the Monday evening event as a celebration of poetry. It was interesting that Professor Humphrey Ojwang, UoN’s Director, Department of Anthropology, Gender and African Studies, called Taban “an ancestor in his lifetime”. The term brought a whole new meaning to ‘ancestor’, which means a person, typically one more remote than a grandparent, from whom one is descended. With the hall easily representing four generations, there was no denying the intergenerational mutual dependence between young and old and a sharp rebuke to the invasive cancer of ageism especially in the workplace.

A few words on the poem’s subject matter. Did Troy exist? You might well ask. In the verse: “there was never a troy except the morality play as vehicle for religious warnings dutifully chorused./a heroic age ends in the deaths of heroes, some in battle, some in bathtubs, a few out of old age, or natural deaths./and those the new gods love survive to draw a moral half human, half-goddess helen lives twice with husband Menelaus.”

Contrary to what Taban suggests in the above verse that Troy, which is believed to have been somewhere north-west of modern-day Turkey, John Jackson in the introduction begs to differ. “It is hard to imagine ancient Greek and Roman literature without the war between the Greeks/Achaeans and the Trojans (the inhabitants of Troy) (the Trojan War.” Jackson views the memories of that war as having inspired “the two mighty epics attributed to Homer, the Iliad and the Odyssey.”

While Jackson believes that there was, indeed, such a war as the Trojan War, he is not convinced by suggestions that it was all about competition for trade routes, the desire for more and more mineral resources…(do I hear Kenyans adding lust for more and more land in the mix?) On the contrary, he invokes the authentic Homer, whose epic revolves more around love, lust, jealousy and revenge — universal and timeless themes. Only this week, Kenyans were shocked by two siblings one of whom killed his senior brother in a love triangle involving their step sister.

Taban does not dispute this. In fact, he regaled his audience with an anecdote in which he chided students who once admonished him for treating them to what they termed as obscenities. He reminded them that thanks to what they regarded as obscene, they were alive to listen to his lecture.

What does a reader make of after troy? It signifies the universal nature of literature. Then as now, men still insist on virgin wives, never mind that ‘un-virgin wives’ (my coinage) are made so by un-virgin men. This brings into sharp focus the raging debate about teen pregnancies. Inasmuch as the focus has tended to be on the girl child, who, today, is a target of contraceptives, there will be no end to her plight unless sex education targets both boys and girl.

Hate him or love him, Taban’s after troy is a must-read for students and teachers of literature not just because of its literary value, but also because of its universal sociocultural lessons.

Ms Kweyu, a consulting editor, is a former student of Taban lo Liyong. [email protected]