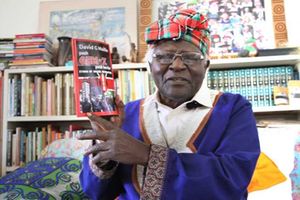

Professor Ratemo Michieka addressing participants during his book launch, “Walking the Promise” at Sarova Panafric Hotel, Nairobi on August 18, 2023.

I am reading, and enjoying, a book by my friend and former neighbour in the Ruiru-Juja area, Prof Ratemo Michieka. The book is titled Walking the Promise, and it is a strikingly level-headed, not to say understated, autobiography of the illustrious professor. I do not, normally, review books here, as you know, because I am not very good at it, and we have specialists in that area.

But I thought I should mention the book to you for three main reasons. The first is that it is an impressively well-written book, with a fluent and persuasive readability. Secondly, it is an inspiring portrait of a genuinely committed scholar, teacher and leader. My third reason for singling out Prof Michieka’s Walking the Promise is that I happened to be reading it during the week when we are contemplating the phenomenon of longevity. You noted, no doubt, that we marked the International Day of the Aged last Tuesday, October 1.

Regarding readability, I confess that my expectations of the many biographies and autobiographies that roll off our presses every year have remained rather low over the years. Those that I have read tend to be either plain, linear narratives or, especially from politicians, thinly-disguised attempts at justifying the authors’ doings and misdoings. I remember my friend, Prof Henry Indangasi, undertaking an extensive study of biography and autobiography. Maybe reference to his work could help us identify the criteria and expectations we should make of these “life (self)-portraits”.

Prof Michieka’ autobiography manages to give the reader not only an account of the author’s life story but also a strong sense of the times and circumstance through which the story unfolds. More importantly, there is a consistent and continuous interpretation of the events and experiences narrated, and their significance for the present-day reader.

This is the work of an obviously seasoned educationist gently suggesting to fellow educationists the advantages and challenges of requirements like discipline and its application. Walking the Promise is an insightful illustration of how a good education forms and transforms us, and Michieka’s journey turned him into a formidable scholar and public servant.

You may have heard that Prof Michieka was recently installed as the first Chancellor of the Tharaka-Nithi University. That certainly is a long walk for a boy who set out from Nyamagesa Village in Kisii County 75 years ago. People often say that the office of University Chancellor is largely ceremonial. It is, however, not negligible. Many of us may remember the days when the Chancellorship of our public universities was reserved for Heads of State. In any case, Tharaka-Nithi University is bound to benefit from Chancellor Michieka’s vast experience, even if in an advisory capacity.

After all, Prof Michieka is famously credited with being the founding Vice-Chancellor of the Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology (JKUAT). He led that august institution for 13 years, without ever facing a student strike, riot or demonstration in a period when student unrest was rife. Those who know this quiet-spoken yet highly articulate scholar attribute this feat to his remarkable negotiation skills and his warm empathy with his colleagues and his students.

Even the most selective mention of Prof Michieka’s outstanding performances on the Kenyan and international scene would leave us little space and time to discuss anything else in our chat. Apart from being an Emeritus (honourably retired) Professor of Kenyan public universities, he is also a Distinguished Professor at Rutgers University, his alma mater, in the USA. Academically, he is an eminent agriculturist and environmentalist with specialisation in East African weeds. His roles as Director General of the National Environment Management Authority (NEMA), Chairman of our own KU University Council and of the Inter-University Council of East Africa (IUCEA) also readily come to mind.

But to relate all this to the International Day of the Elderly, you may have noted my referring in passing to Prof Michieka’s age. He is in his mid-seventies but he shows no sign of slowing down. He is still in strong and vigorous charge of various public and private organisations and he participates as a member in or advisor to many others. Is he old? Should we be preparing to welcome the Prof into our distinguished club of octogenarians, nonagenarians and centenarians? I will leave the answer to you.

My take on the matter, however, is that we have to start seriously re-thinking and redefining “old age” and “old people”, and our attitudes to them. In fact, a lot of forward-looking people are already doing this. Note, for example, the shift in terminology from “old people”, the “aged” to “seniors”, “elderly” and my own favourite “grownup”. This is not only to avoid derogatory and demeaning references but also to suggest and expect positive value from our seniors.

This is imperative, especially in the face of the fact that people are living longer. This means that they will remain active and relevant way beyond the years traditionally considered as ushering in “old age”. The retirement age at Makerere University, for example, was 60 years until the early years of this century. Indeed, when I clocked 60 in 2004, I was expected to retire. Only, those conventional institutions were slowly waking up to the reality that retiring people at 60 was a wasteful mismanagement of human power, to the delight of the mushrooming private universities, which snapped up the seasoned professors’ and lecturers’ services.

That is when the conventional institutions brought in measures like raising the retirement age to 65, and offering the retiring but “deserving” senior academics two-year renewable contracts. Still, that is not progressive enough. The latest expectations of the senior citizens is that people should be left to work as long as they were demonstrably capable of carrying out their duties. Sending them home on the strength of mere numerical years, they say, is “ageism”, discrimination comparable to sexism or racism.

The theme for this year’s International Day of Older People, as they called it, was “ageing with dignity.”

Prof Bukenya is a leading East African scholar of English and literature. [email protected]