In Harry Belafonte, Kenya and Africa had a great friend

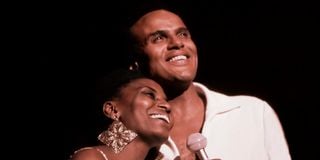

Harry Belafonte and Miriam Makeba during a past performance. Belafonte died on April 25, 2023. Makeba died on November 10, 2008.

Independence hero and iconic politician Tom Mboya first met American stars Harry Belafonte, Jackie Robinson and Sidney Poitier when he was co-ordinating an airlift of 81 Kenyan students to the United States.

That was the beginning of a sensational love affair between musician and activist Harry Belafonte, who died this week on April 25, and Africa — especially Kenya — which he visited as often as possible. With funds from an “African Freedom Dinner” night and with the help of Martin Luther King and other African sympathisers, Mboya was able to raise enough money to fund the airlift.

In the years that followed, Mboya continued to work with both black and white friendly Americans in the interests of Kenya and other African countries. Belafonte made his first visit to Kenya in 1963 in time for Kenya’s Uhuru celebrations. He brought with him his South African singing friend, the great Miriam Makeba.

At the celebration, President Jomo Kenyatta ensured Belafonte and Makeba had the best seats in the house, next to the Guest of Honour, the late Prince Philip. They were guests of a wonderfully outstanding Goan businessman, the late Pius Menezes. He was a representative for the American recording company, RCA.

He also sold a variety of audio-visual equipment (record players, amplifiers etc). He was also a celebrated Queen’s Scout and a well-known high-flying Rotarian. Pius had been instrumental in getting the duo to sing at Kenya’s Uhuru celebrations and later at a special “welcome to Kenya” celebrated at the Nairobi Goan Gymkhana.

Pius also had close friendships with Chet Atkins, Jim Reeves (who used to call Pius regularly) and many others including Elvis Presley, Louis Armstrong and others.

Pius invited me to his offices (we used to meet regularly there, he was always sharing music related tips for a story) and there was a pleasant surprise waiting for me: Bellafonte. I remember we spoke for a few minutes, laughed a little and wished him well.

In his spare time, Pius used to visit schools in Nairobi and wherever else he could to show movies to young children, free of charge, of course. Thanks to Pius, I saw my first movie at the age of five or six years old.

Many, many years later, The Washington Post said: “If we had struck an honourable treaty with a lot of these countries at the end of the colonial era, a lot of these troubles we are facing with them today would be non-existent,” Belafonte told Calendar during a break last week in his USA for Africa tour of Eastern Africa.

“But Belafonte said that he believes the United States was responsible for upheavals, perhaps even assassinations, “thinking we could have our own way.

“So, a lot of moderate guys are killed off in the beginning of African independence and we just polarized everything. In come the Soviets and they find this situation where they can push their thing. A lot of the loyalties you find in a lot of these countries can be traced back to the rebels who fought against the colonialist onslaught. The only really friendly persons around for a lot of these guys - especially young minds caught up in the fever of independence - were the Marxist forces.”

Bellafonte brought his own, clean-speaking, no-holds-barred kind of diplomacy.

Freedom

That same nationalistic fervour among the underclasses from Jamaica to most of Africa came with the end of World War II, according to Belafonte.

“At the end of the war, I think most of the countries thought they could go back to business as usual. But they discovered something that had not existed before: wars of liberation.

“The French found out when the Vietnamese said, ‘Uhn uh, we fought the Japanese as allies, we had a taste of independence, and we want it too.’

“The British found the same thing in Kenya. The Belgians found it in the Congo. All over the globe, there was this massive eruption of people whose appetite was whetted with a new desire for independence and self-determination.”

Ethiopia is a textbook case of how US policy failed, according to Belafonte. There, Emperor Haile Selassie I ruled with an iron fist until he was overthrown by Mengistu Haile Mariam in 1974. Despite the gross inequities of his government, rewarding a tiny ruling elite while most of the country lived in abject poverty, the United States supported and recognised his regime for almost 50 years.

“I don’t know if the West gave the Ethiopians a lot of options. They chose Marxism. But no matter what I think about an ideology, I have to put it into a context. I find Marxism and communism as diverse as Christianity. You got your Roman Catholics, you got your Mormons, you got your Episcopalians, you got your evangelical groups. So, I can’t come to a place like Ethiopia with so simplistic a point of view as Marxism is bad or good.

“As China has visibly displayed, there is a very different line between what they want to do and what the Soviets want to do. Maybe there’s a different line with Ethiopia too.”

The Belafonte diplomacy doesn’t always go through channels. He tolerates, sidesteps, and even ignores government bureaucracy. Instead, he croons his apolitical call to aid crippled populations directly to the people. (The Washington Post).

Through UNICEF, Bellafonte was able to dedicate himself to the length and breadth of Africa. When Kenya introduced free education, he was the first to applaud.

Since the first week of tuition-free school in Kenya in January 2003, more than 1.3 children have entered school for the first time, pushing national enrolment from 5.9 million to 7.2 million, according to UNICEF.

“These children and their parents know that getting an education is not only their right, but a passport to a better future,” Mr. Belafonte said. “Kenya's decision to abolish school fees is a shining example of just what can be achieved in the developing world by sheer political will.”

Belafonte was visiting Kenya to monitor the success of free primary education one year after school fees were abolished. Appointed as a global Goodwill Ambassador in 1987, he has participated in hundreds of events and trips on behalf of UNICEF. He has urged other countries to follow Kenya’s example of free primary education.

Arguably his greatest contribution was his campaign in the battle against Aids in South Africa and later in other countries.

Being a driving force in the civil rights movement in US, it was little wonder that he was a powerful driving force against apartheid in South Africa, or wherever he came face-to-face with it.

- Cyprian Fernandes is a Kenyan-born journalist, who worked for the Nation Media Group in the 1960s and left as a chief reporter. He now lives in Australia.