Egara Kabaji releases a new book with an unusual title

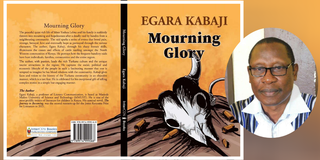

Novel Mourning Glory. Inset: the author Prof Egara Kabaji.

What you need to know:

- Reviewer: Peter Amuka

- Book title: Mourning Glory

- Author: Egara Kabaji

- Publisher: InterCen Books Publisher: InterCen Books Publishing Company

- Year: 2022

Just when I believed I was inching close to the last creative work by Egara Kabaji, in came his adult novel with an ironical eye catching title, Mourning Glory. Reading his books is like scaling up a very steep mountain. They are more than thirty and easily qualify him to compare favourably with or rival his seniors Ngugi Wa Thiongo and David Mailu.

From the very first page of Mourning Glory, it is obvious that the emblazoning of the novel’s cover with the image of a bull’s head is not mere decoration: Mzee Lelma, the main character, is thoroughly dejected in a very mournful mood because of the theft of his livestock.

Of his 1,000 goats, 850 cows and 300 camels, only three white goats have been spared by the raiders.

Turkana County is the crime scene and the prime suspects are believed to originate from West Pokot County.

The act of raiding and depleting Lelma’s kraal is known as cattle rustling in Kenyan parlance. This is but just one event that breeds hatred and suspicions between the Pokot and Turkana communities. Kenya’s colonial government created a special paramilitary police known as the Anti- Stock Theft Unit but they were unable to contain the menace. The post- colonial government retains the same unit and continues with the policy of using force to eliminate livestock theft. This is to say that state coercion rather than persuasion persists as the mode of management

Mzee Lelma thinks and acts differently, and unlike the state, avoids violence and the use of the bullet. He takes the romantic route. Against all ethnic odds and suspicions he marries Leleve, a bewitchingly pretty charcoal-black Pokot lady.

The way the narrative is positive and romantic in describing Leleve, one would imagine that the marriage should lead to peace and unity between the Pokot and Turkana. To the contrary, some Turkana neighbour of Lelma’s suspect that his wife may have conspired with her Pokot community to raid.

She is likened to the mythical Kalenjin lady who betrayed a Luo warrior by revealing that to subdue him one only needed to spear his shadow. No proof is adduced to corroborate the Samson-Delilah suspicion of Leleva that she may have conspired with the Pokot raiders to steal her husband’s livestock. It typifies the distrust that reigns and underpins sociopolitical relationships all the way to the bedroom.

The antithesis of individuals hell-bent on highlighting the differences, and therefore the negatives, is Mzee Lelma. To state the obvious, his marriage is an attempt to bridge ethnics differences and stop the chronic practice of stealing or raiding for livestock.

As the narrative unravels, it becomes apparent that interethnic marriage cannot pass as a panacea for ethnic conflicts.

Moreover the Lelma-Leleve relationship amply shows that despite the many solemn holy vows couples make to live and love one another forever, there almost always are many undercurrents of doubt and shortcomings. Simply stated cohabiting and coexistence can thrive and tolerate differences.

For purposes of appreciating and understanding the drift of the whole story beyond the Lelma family, their marriage is a microcosm of the elusive and slippery love, peace and unity being sought for the Turkana and Pokot as much as it is for Kenya as a nation. It is a story of counties that were as neglected and underdeveloped by the colonial state as they remain outside mainstream post colonial Kenyan infrastructural and cultural growth.

Another way of putting is that the novel’s storyline is about spirited attempts to create the requisite love, peace and unity that Kenyan nationhood requires but lacks. It ought to necessarily begin from the grassroots or counties and grow upwards in to the nation. But it isn’t quite that. The state attempts to pacify the restive regions from outside by deploying clueless, inefficient, indifferent and ill- informed officials: the centre (state)is trying to shape the periphery (Turkana and Pokot) but does not know how to do it.

Mzee Lelma represents the grassroots. His foil in the well- dramatised search for harmony is Tembeta while his supporters are the young Turkana professionals who seek to run and sustain the county differently. As they say and imply, the “science of hunger” can be best understood and applied by the people who know, feel and can navigate the local situation. Tembeta opposes this and is embroiled in a political fight against Lelma and the youth.

Ultimately, Kabaji’s story transcends Kenya. Alu, Lelma’s son is going to school in the United States. He panics because the raid means his father can no longer support him financially. Racist ill-educated Donald Trump is not only the president but is also anti- black. In addition, Alu has a troubled love relationship with a white American woman who, accidentally, gets pregnant, with a white former boyfriend. The world certainly lacks what the narrator calls “good virtues.”

Seriously, one cannot possibly expect virtues from a world with an extremist right wing as president of a purpoted superpower. Nor can Kenya claim to be virtuous. The massive livestock raid whose effects ring and run through the Turkana-Pokot story is symbolic of the huge deficit in morality in the country.

There is a lot of glory in searching for a stable moral centre for humanity and Mzee Lelma deserves lots of praise for this. Yet his assassination is for me the worst event in the novel. Bad politics kills him just like that bull. His death bespeaks the history of assassinations of the virtuous, patriotic and Afrocentric in African political history.

Lelma is the Turkana Nelson Mandela when his arrest and detention is made to echo the latter’s confinement on Robben Island in the bitter struggle for his people’s liberation.

Mention of randy, sex maniac Mobutu of Congo evokes memories of Patrice Lumumba’s murder and dissolution in acid by Belgians and Americans. Again Lelma is the Turkana Lumumba. A dunderhead called Ipera (a kind of Mobutu) has eight wives but chooses to humiliate him (Lelma) by marrying his daughter as the ninth wife. Sadly he is too drained to consummate and his son takes over. The youth should be allowed to rule and modernize their Kenyan counties.

Ipera’s impotence reads like a subtle condemnation of the political leadership that triumphs over Lelma’s progressive vision and dead body. It is a mockery of democracy and the vote as the bullet kills youthful leadership.

The juxtaposition of the words “mourning” (gloom) and “glory” (joy) initially gives the impression of a story of a single cataclysmic event. Yet as Lelma dies from the shooting and concludes the novel, a reader has navigated a very rich tapestry of interrelated and interweaving human events and activities with a large tissue of Kenya’s post- colonial history of conjoined twins of gloom and pain for the majority and joy for the minority like Ipera.

- Peter Amuka is a Kenyan professor of Comparative Literature. [email protected]