China pings in Kiswahili, and not a French word from me in 2 days

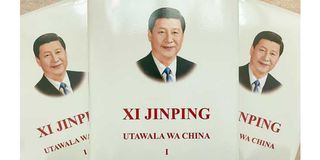

The cover of Xi Jinping’s ‘Utawala wa China’.

Utawala wa China is the title of a new Kiswahili book launched at the University of Nairobi Main Campus on Monday this week. I understand that the book is a translation from Chinese of a work called Xi Jinping: The Governance of China.

I believe the book was authored by the Chinese leader, Xi Jinping. So, I am respectfully joking that Chinese governance is being “pinged” to us in Kiswahili.

Kiswahili was, of course, the bait (chambo) for my attention to the high-profile event, graced by our CS for Tourism, Wildlife and Heritage, Ms Peninah Malonza, her counterpart from China and the Chinese Ambassador to Kenya.

I certainly am not minimising the diplomatic significance of the launch, which Ms Malonza underlined. Nor should we underplay the obvious need for close international friends to share views, experiences and experiments in leadership styles.

But what particularly delighted me was that all sides had seen and acted on the desirability of spreading this information in the language of East African wananchi. Jameni, now we have no reason for complaining that “we don’t know what the Chinese are all about”, since they are telling it all to us in our own tongue. Indeed, they should tell us more, in Kiswahili, about their famed appropriate technologies, their legendary medical skills and their age-old philosophies.

Communication with Africans in African languages is not only a gesture of respect to them but also the most effective way of sharing our experiences and mutual interests and objectives.

China has been active in promoting its linguistic communication with Africa. She has established Chinese language study centres, the Confucius Institutes, at many of our universities, and there is a growing study of African languages, especially Kiswahili, at Chinese universities.

The production of relevant teaching, study and other information materials is, of course, essential in the process of promoting Sino-Swahili linguistic proficiency.

China’s specific recognition of the primacy of Kiswahili in this process is of great significance to us addictive “swahilivists” (Kiswahili activists). For decades, we have been preaching the significance of Kiswahili as a language of international communication in East Africa and beyond.

Recognition by a country like China, with an estimated population of nearly 1.5 billion, is no mean development.

Nor is it a random or accidental happening. As the Chinese Ambassador hinted at the Monday ceremony, China could not afford to ignore the over-200 million East Africans who communicate habitually in Kiswahili. Hopefully, China’s move will be followed by other countries. I will not mention India too loudly, but you know.

The irony, however, would be if, with all the growing international recognition for our language, we Waswahili (East Africans) were to remain trapped in any kind of hang-ups, inhibitions or embarrassments about it.

These range from sheer ignorance (insufficient competence) of it, through careless and reckless creolisation (sheng) mutilation to the insidious “kasumba ya ukoloni” (colonial hangover). This last one is the assumption that the colonial languages are better suited than Kiswahili to the discussion of “serious”, official and important matters.

But we should not be unnecessarily pessimistic or despondent. As I have been pointing out recently in these pages, there are many positive developments on the Swahili front in all our countries.

These include the almost universal teaching of Kiswahili throughout our educational systems, the expansion of Kiswahili media channels, the establishment of national and regional language governing and regulatory bodies and the rise of professional, scholarly and advocacy associations.

A great deal remains to be done but we are on the way there, if we keep our vision clear and our purpose firm. “Penye nia pana njia” (where there is a will there is a way), as we say.

Indeed, one of these positive developments dawned upon me as I thought back on the International Kiswahili Day celebrations we had in Kampala last month.

I mentioned to you that the bulk of the proceedings was in Kiswahili, despite the recognition of English and French as working languages of the East African Community, under which the East African Kiswahili Commission, our host, falls.

I was, without exaggeration, deeply impressed by the fluency, the articulateness and the elegance of the Kiswahili in which all the delegates from the seven countries made their presentations.

But it was at a personal level that I realised how our minds can be positively conditioned to use language as required. Being a sort of “loose local”, I was not attached to any national delegation.

So, I quietly drifted to the Burundi delegation’s table, and I ended up spending the two solid working days of conferencing with them. One of the reasons I joined them was that I recognised among them Dr Denis Bukuru, an old friend with whom I had previously worked at other Swahili fora.

But there were also two young ladies there who, curiously, reminded me of one of my most admired Kiswahili broadcasters, the late Hafsa Mossi. Ms Mossi distinguished herself at the BBC Swahili Service in the 1980s, before returning to Burundi, serving as a government minister and representing her country at the East African Legislative Assembly.

She was, disastrously, assassinated in Bujumbura during one of those upheavals Burundi has periodically suffered since its independence.

Now, the Barundi (Burundians) are “Francophone”, and what surprised me, in retrospect, is that in all the time we were at the celebrations, I had not spoken any French to them. Usually, when I meet speakers of French, I am eager to chat with them in the “langue”, and they often appreciate it.

I, too, find it an enjoyable and useful way of keeping alive my fluency in the language. But my new friends in Kampala spoke such natural and fluent Kiswahili it just did not occur to me to speak to them in any other language, not even in Kirundi (Icirundi), of which I know a few phrases.

Is this the future of the Jumuiya?

- Prof Bukenya is a leading East African scholar of English and [email protected]