150 years of journalism in East Africa: Pioneers tell their tales

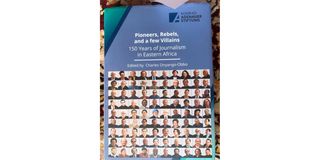

The cover of the book 'Pioneers, Rebels and a few Villains: 150 Years of Journalism in Eastern Africa' edited by Charles Onyango-Obbo.

What you need to know:

- One of the aims of the book is to recognise and put on record the forgotten journalists who paved way for the new age of journalism in Eastern Africa.

- In one of the most compelling chapters, the book sheds light on one of the biggest discrepancies in journalism: Gender disparity.

There are few professions in our world filled with unsung heroes; heroes who are willing to fly too close to the sun and risk melting. They risk burn-out due to exhaustion, all in the name of feeding an entitled beast with an infinite capacity that relentlessly asks for more.

One of these professions is journalism. For a category of professions whose bread and butter comes from telling stories, it is quasi-ironic that their own stories are rarely told. This reality becomes apparent as you skim through the book, Pioneers, Rebels and a Few Villains: 150 Years of Journalism in Eastern Africa.

Charles Onyango-Obbo — the editor — opens up the book with what seems like an editor’s note, titled ‘Introduction of madmen and madwomen.’ He explains the aims of the book; revealing, in vivid imagery, how a rainy morning in Kampala sparked the idea to work on a book that would seek to explore the events of journalism in Eastern Africa.

In the chapter, he notes candidly that one of the aims of the book is to recognise and put on record the forgotten journalists who paved way for the new age of journalism in Eastern Africa. While doing so, the book is in a quest to understand “why African journalists continue to put their necks on the line in perilous environments while stirring further exploration and get a younger generation of journalists and creators of content to tell their stories in new ways.”

Instead of telling the Eastern African journalism story as one of torment — as is wont of many publications — the book focuses on telling individual stories of journalists surrounded by different circumstances but, more specifically, “exploring how they lived, live and why they still go out daily to do this dangerous and thankless work.”

It is due to this that the book is segmented into different ‘chapters’ that not only explore different time periods of journalism in Eastern Africa, but also shed light on the various forms of journalism that have shaped the industry today.

Such is photojournalism.

In 1871, Welsh-American journalist and explorer, Henry Morton Stanley, got a scoop of a lifetime when he found the missing and ailing David Livingstone in a village along the shores of Lake Tanganyika. In the first chapter of the book, 'Henry Stanley’s Heirs,' Morris Kiruga — the contributing author — looks at how foreign correspondents defined Africa while unravelling the intricacies of the history that encapsulates the relationship between foreign correspondents and Eastern Africans, both in the colonial and post-colonial eras.

Gender disparity

As the book notes, that relationship settled into an uneasy balance: On one hand, the locals viewed them (foreign correspondents) with suspicion, as colonialism’s tail end, but they also considered them important to “communicating with their former colonial masters and the wider world, outside of diplomatic channels.”

Not surprisingly, foreign correspondents had it easier during the colonial times than they did in the post-colonial era. All around the region, a good number of foreign correspondents were deported by uncompromising African leaders. Regardless of the hostility, the foreign press proved an effective platform to showcase the plight of Eastern Africans when it came to natural disasters such as drought, famine and floods.

A good example given in the book is that of South African photojournalist, Kevin Carter who, in 1993 while covering the war in Sudan, captured an emotive shot that would go on to grab global attention and land him the kind of jobs and access that many photo journalists could only dream about.

The photograph captured — as detailed in the book — shows a little starving girl with a white necklace. Her head on the ground, “in what appears as a pose she fell into rather than chose.” Behind her, a vulture lurks. The little girl’s fate became a subject of heated debate, prompting the The New York Times, in a special editorial, to note that the vulture had been chased away: The overhanging question that remained unanswered was whether “she (the girl) reached the (feeding) centre.” In 1994, however, the revered photojournalist “was found dead in his red pickup truck in Johannesburg, a suicide note placed on the passenger seat.” This was only two months after he had won a Pulitzer Prize for feature photography.

In one of the most compelling chapters, the book sheds light on one of the biggest discrepancies in journalism: Gender disparity. In a chapter dubbed, “Cracking the Glass Ceiling,” Brenda Wambui — the Contributing author — begins by highlighting the career of Eunice Njambi Mathu, founder and editor in chief of Kenya’s longest running print magazine, Parents. Mathu had dived into publishing earlier in 1984, when she started Consumer Digest, but Parents’ success, after hitting the vendors’ rack in July 1986, would lead to Consumer Digest Closure.

The chapter consequently highlights how Mathu’s earlier steps and efforts, together with those of other female veteran journalists, such as: Serah Elderkin (former Deputy Editor of The Nairobi Times), Catherine Gicheru (who became the founding editor-in-chief of The Star newspaper in 2007) and Pamela Makotsi-Sittoni (who, five years later after Gicheru’s appointment, became managing editor of The East African), compounded to “Cracking the Glass Ceiling” for upcoming female journalists.

Unexpected storm

As Brenda puts it: “For women journalists, it once looked nearly impossible to get in. Now that the glass ceiling has been cracked and some have made it, the price many are having to pay is very high.”

In its last few pages, there is a palpable sigh of despair in a chapter titled, “And Along Came Covid-19.” Rita Nyaga narrates how the unexpected storm that rocked the globe took a toll on journalists and media houses across the region.

Survival at this point called for innovation and ingenuity. The reluctance to embed digital in news transmission felt like a blow in the gut for media houses. For journalists, despite the perilous nature of the assignment, many of them risked skating on thin ice to unravel the mysteries that surrounded Covid-19.

Of the many challenges that emanated from the virus, one of the most notable was the circulation of the print newspaper. The book details how Nation Media Group’s (NMG) “sardonic” editorial director, Mutuma Mathiu, together with Churchill Otieno, NMG Head of Development and Learning, led a charge by NMG, at the height of the pandemic, to transform into a fully digital brand, “a move the company had been taking in baby steps for nearly 17 years.”

Consequently, in September 2020, the Daily Nation was re-launched as an Africa portal Nation Africa. As the books highlights however, “this was a rare spot of good news for Eastern African media in the pandemic.”

Many journalists lost their jobs as many media houses were almost pushed to complete closure. It is a reality painfully described by Nyaga; “Covid-19 could result in easily one of the largest physical dislocations of journalists in Eastern Africa, and their exit from the middle class, of recent times.”

Kevin Maina is an editorial, digital marketing and broadcast intern. [email protected]