Hire Wanjiru Waithaka, narrate your story and see it become a book

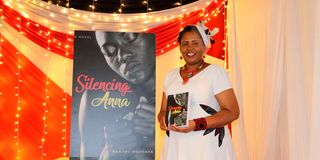

Wanjiru Waithaka during the launch of her third novel ‘Silencing Anna’ in December 2022.

Whenever Wanjiru Waithaka is paid to write someone’s story, she first buys at least three books. She will shop for the hottest biographies and autobiographies in the market to acquaint herself with the latest writing trends.

That is one of her ways of researching before she pens a person’s life story in a book.

“When I get that first advance, I buy about three or four books that everyone is saying are the best to see how things are evolving in the writing space,” she says.

Wanjiru, 50, is a ghostwriter. She is paid to write stories and reports for people but is often not credited as the author.

She has helped to develop two published biographies so far involving top leaders in the country. One, about a renowned business titan, who will not be named because of issues that arose after the publication of the biography. The other is Kenya’s Tax Czar, the autobiography of former Kenya Revenue Authority Commissioner-General Michael Gitau Waweru.

Wanjiru played a key part in piecing together Mr Waweru’s autobiography, which was released by East African Educational Publishers in 2021 and was serialised in the Nation. It has been praised for its rawness and storytelling prowess.

Wanjiru Waithaka (right) in 2021 during the launch of ‘Kenya’s Tax Czar’, an autobiography of Michael Waweru (second left), the former Commissioner-General of the Kenya Revenue Authority.

She was also involved in the 2014 book, A Profile of Kenyan Entrepreneurs, which detailed stories of various high-flying businesspeople in various fields and their highs and lows in business. But this commissioned project was different as her name was included on the cover alongside the co-author, Evans Majeni.

Besides biographies, she also has three novels to her name. The debut novel, The Unbroken Spirit, was first published in 2005 by Spear Books. In 2007, it came third in the Jomo Kenyatta Prize for Literature.

Her second novel, Duel in the Savanna, was released digitally and is available for free on her blog. Her third work of fiction, Silencing Anna, is a 391-page self-published novel that was released in December 2022.

The current biography she is writing involves a young woman who died at 21 and whose parents want a book written about her.

Wanjiru sat down with Lifestyle and discussed the process of writing other people’s stories, why she dreams of a time when she can write fiction the whole day, and why she doesn’t like working with politicians.

“I am a storyteller. I see a blank page and just want to fill it with words. Other people play a sport. Dance. Drink. Worship. I write,” she says of herself on her blog.

For someone with a bachelor of commerce degree in marketing and a master’s of business administration in strategic management, both from the University of Nairobi, Wanjiru describing herself as a writer sounds quite like the perfect tale of a career detour.

But when you consider that a good chunk of her writings involves people in business, it strikes you that she is putting her classroom knowledge to use. She says she was once encouraged to write by one legal scholar when she was working in a non-governmental organisation.

“I was really admiring his work. And he was like, ‘You know, you can also write.’ I laughed. I was like, ‘Please. You guys are professors. What should I have to say?’ Twenty-six years later, here I am, releasing the sixth book. So, maybe that’s what planted the seed and the whole writing thing,” said the alumna of Precious Blood, Riruta.

Her interest in the written word plus her academic credentials also saw her report for the Business Daily in its early years in the market.

Wanjiru Waithaka with Michael Waweru, the former Commissioner-General of the Kenya Revenue Authority.

Wanjiru’s world of ghost-writing autobiographies is one that requires her to immerse herself into the subject, to research widely, to encourage people to open up and to look for publishers to convert manuscripts into sellable books.

“(The work is) in two parts. The first part is generating a manuscript. Then the second part is that once you have something to work on, now you start shopping for publishers. That’s why I always separate those two because while I have control over the first part, I have no control over the second,” says Wanjiru.

Writing someone’s story involves having numerous sessions with them, recording interviews and later typing them out and piecing them together into a story. It takes at least two years to have a significant end-product, she says.

She will listen to the recorded interviews and study the transcriptions of the same to get in sync with the person’s thought process.

“As much as possible, I want to channel this person. The more time you spend with them, the more you get to understand how they talk, how they reason, and then now try to capture that in writing,” she says. “For me, the best thing is when someone reads they say, ‘Oh, this is how I really talk.’”

The first step towards writing a biography is holding a meeting to agree on the journey to take. Experience has taught her not to commit to writing a person’s story before meeting him or her in person.

“I do not take a project before I’ve met you in person. There’s something called chemistry. A book is a very long process. For a minimum of one year, you’ll be with this person. If you don’t get along, it’s going to be a real problem. Some people can work with anyone, but for me, I have to meet you,” she says, noting that she once took up a project but it turned out that the person to be interviewed had dementia and it was a difficult task generating material.

The amount she charges depends on the amount of work to be done. The longer the story, the more she charges. Some people also like to have various people interviewed and that will have cost implications.

“It’s hard to give a rough figure,” she says when asked how much she charges for a typical autobiography. “And that is why you must have that first meeting with someone.”

She says that a story of a 73-year-old who has worked in various sectors cannot compare with that of a 21-year-old.

“There is no way those two projects can be the same. So, you cost based on the amount of work involved and how long it will take to do it.”

Once she has come up with the price, she will ask for an advance before the work gets underway. Most biography writers, she says, have come to understand that some people – especially politicians – hardly pay after the project and so it is good to ask for upfront payment of a good portion of the total sum. Wanjiru advises writers to ask for an advance that can cover the costs in case the person doesn’t pay up in the end.

“There are people who’ve written books for people and have never been paid. In all the cases, it’s been a politician. So, I try to stay away from politicians,” she notes.

Once the payment is done, she embarks on the project. She prefers having the subject as comfortable as possible, so they decide on the venue and the time.

“If they’re not comfortable, they can’t really open up. You know, it’s about introspection; about thinking through. The person has to be comfortable. So, if you need to go to their house, fine.”

Whether the person wants interviews early in the morning or late into the night, she says, she can create time. The idea is to have the person’s life go on as the book is being developed.

“Life does not stop because you’re writing a book,” says Wanjiru, noting that she recently said that to a potential client who says he is too busy.

When interviewing Manu Chandaria for A Profile of Kenyan Entrepreneurs, she remembers, she had to do interviews in his house because there were often many interruptions in his office.

During interviews, she encourages her subjects to let loose.

“So, what I advise my clients is: Please don’t censor at the interview stage.”

She says one trick of doing this is to start with easy questions. But there are times when the person has to answer the tough ones.

“Sometimes I just tell them very firmly, ‘X, we have to talk about this. You go do whatever you have to do, prepare yourself mentally, but this has to be in the book. So, when you’re ready, you come and tell me.”

And as the words get typed and the final product is near, she says, people often suggest the deletion of some sections. She says that many “fights” happen in that stage and she has had to remove entire chapters or water down a lot of details in what goes into the final work.

“There is a lot that people hide,” notes the writer.

Her perfect autobiography is one that is authentic.

“My favourite is a very small, interesting book. It’s titled Dare to Defy by Peter Shompole. Mzee Shompole’s book is so raw. He even talks about his circumcision … (and) he talks about his health challenges.”

She likes the book because the man, despite being an outwardly macho Maasai, admits his vulnerabilities.

“African men don’t want to talk about their weaknesses: losing jobs, losing money, health. Mzee Shompole talked about everything,” she says.

She baulks at some autobiographies in the market, like one done by a former government official who held back a lot.

“So, I was thinking, ‘Then why write a book if you are going to hide behind the Official Secrets Act? Die with your secrets, like the way (former Attorney-General Charles) Njonjo decided to do it,” she notes

In all, Wanjiru wants more people to have their stories written to enrich Kenya’s historical record.

“Njonjo is on record saying he never wanted to write his book. But I kept thinking, ‘I wish, even if you don’t want it to come out when you are alive, if you can write it and then have a caveat that it should only be released after you die.’ Because we are losing the men of that generation. We’ve got people like John Michuki. I mean, when you think about the books that have been written in that era, they are just not there and they are supposed to add to the historical record,” she says.

“And when it comes to corporate leaders, those ones are even fewer. At least politicians try,” she adds.

She has no qualms not being credited on the covers of books she ghost-writes. Using the Swahili saying “chema chajiuza”, she notes that doing a good job will always get someone referrals.

“Even when my name is not here, I still try to do my best. But at least I don’t have that pressure of my name being on the cover.”

Besides biographies, she has also ghost-written newsletters and annual reports.

A core part of writing biographies is getting a publisher. Once she has written and come up with “a happy middle ground” with the person she is helping write, she approaches publishers. Some manuscripts will be accepted; others won’t. Some publishers will recommend more changes, especially if there are libellous sections. Lawyers are often involved in this, she explains.

“That time you’re more of a liaison person than anything else. So, you continue working with them through the whole process, and even helping,” she says.

She advises writers to ensure they have a written contract with the people whose story they are documenting, adding that she has a draft agreement that she gives out for free.

“I share it with anyone who asks me because I want to help other writers. It’s very simple. It outlines who does what and what is what. And it protects you. But don’t sign the contract before you’ve met that person. And deal with them directly.”

Is there a person whose story she is itching to write? After a pause, she lists Mr Njonjo.

“I used to tell people, ‘I will do that one for free,’” she says, laughing.

She also has on her list Naivas Limited’s Chief Commercial Officer Willy Kimani and former First Lady Margaret Kenyatta. She says Mr Kimani’s story “has just the right mix of controversy” because of the brother-to-brother court fight and also promise because of the management structure of the Naivas supermarket chain that has an element of foreign shareholding.

“So, I’m thinking Naivas has a real chance of becoming maybe the first chain to go regional, if not global. I’d love to sit with that man,” says Wanjiru.

And why Mrs Kenyatta? She explains that such people usually have richer stories than even the men at the front.

“Those are the people I’d like to sit with because nobody thinks about them. First, they do their work without being told. They see a lot because they are right in there. So, I’d really love to get a first-hand perspective of what it was like for the president at State House from a First Lady’s perspective,” she says.

On the flipside, Wanjiru also says there are some people whose stories she can’t write.

“There are some projects I have turned down. I have one major weakness: I need to be inspired to do a good job. So, if your story does not inspire me, if I have serious questions about your credibility and your character and how you made your money, I’m not taking it up,” she says.

Wanjiru, who is single and with no children, lives in Kajiado.

“My dream is to sit at home and write fiction full-time. But unfortunately, it does not pay the bills. So, helping people write their stories is what is paying the bills at the moment.”