Philip Kinyinga M’Inoti: Behold the reverend, Njuri Ncheke elder and strict colonial chief!

What you need to know:

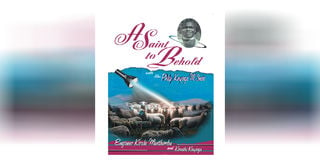

- Title: A Saint to Behold — With the Reverend Philip Kinyinga M’Inoti

- Author: Kiruki Mwithimbu and Kimathi Kinyinga

The introduction, growth and development of the Methodist Church into the predominant religious institution it is today in the Meru counties on the slopes of Mt Kenya was the work of white missionaries with the stellar contributions of their pioneer African converts.

The history of this Christian denomination is also the story of one of the early converts, Philip Kinyinga M’Inoti.

In this book titled, A Saint to Behold with Rev Philip Kinyinga M’Inoti, co-authors Kiriki Mwithimbu and Kimathi Kinyinga, the latter being this great man’s son, have chronicled everything as it panned out from the very beginning in the early 20th Century.

Fondly known as Biribu, a corruption of his English name Philip, the man packed a lot in his nearly five-and-a-half decades of life that ended in a tragic road accident.

This biography of the Reverend M’Inoti is also a rich and well-told account of the history of the colonialisation of Kenya, and the Christian missionaries’ onslaught against cultural traditions. European colonisation wrecked traditional African societies and exploited economies.

The so-called “white man’s burden” was used to justify imperialism and consisted of the three Cs: Civilisation, Christianity and Commerce.

From early in his life, M’Inoti had showcased leadership qualities, emerging as a champion wrestler, getting converted to Christianity and escaping a church fire in 1914 set by Meru warriors opposed to the new religion, his work as a church minister, a traditional Njuri Ncheke elder and the Chief of Miiriga Mieru before his before his death in a road accident in 1952. He was one of the five survivors of the attack on a dormitory that had 11 youth.

One of his most pivotal contributions in the 1940-1950 decade was in promoting education. This saw the emergence of Kaaga Girls School, and Meru Teachers College, with the Rev Biribu effortlessly combining his roles as a religious leader and a colonial chief.

As the authors explain, he found himself as confidant on both sides of the divide – as a reverend and a Njuri Ncheke elder but executed both with dexterity.

In the foreword, Prof FX Gichuru, writes that the foundation of the Methodist Church in Meru is seen in this narrative. It helps one to understand the culture of the Amiiru, and their interactions with the missionaries and the effects of colonisation on the people.

M’Inoti was born in 1895. In about 40 years, until his death in 1952, he served as an evangelist and an ordained minister. He was also a councillor in the Local Government, a secretary of the Njurincheke Council of Elders, and finally, the Chief of Miiriga Mieru (1948 to 1952).

Upon his death, most of his well-preserved records and research materials were taken away. His church and colonial government associates picked the best. Indeed, this was the modus operandi of the colonialists and explains how Africa’s treasured sculptures and artifacts ended up in museums in Europe.

An ally of colonial administrators

Under pressure from Africans after independence in the 1960s, some were returned but many, including the skulls of some anti-colonial heroes such as Kenya’s Koitalel Samoei, are still hidden in European vaults or are on display in libraries and museums.

M’Inoti, the authors state, was an enigma, in fact, a Meru legend. He contributed immensely to preserving Amiiru culture, promoting literacy and religion and colonial rule. He became an ally of the colonial administrators, and adopted their ways, building a stone house and buying a car in the 1950s. He also wrote several books on Meru history and culture.

His unpublished manuscripts were carted away to the United Kingdom and United States. His Wuui wiji atia! a classic Kimiiru must-read of the 1950s and 1960s, was one of his major works.

A legacy of the Methodist Church and the Rev M’Inoti lives on in schools and hospitals. Kaaga, where the Methodist Mission was first established in 1912, is today the epicentre of learning and medical care. It has primary and secondary schools, the Main Campus of the Kenya Methodist University (KeMU) and Level Five Hospital at Maua.

The story of Kaaga Mission starts with colonial District Commissioner Edward Butler Horne, the man the Amiiru nicknamed Kangangi, meaning the wanderer, for his footloose style, allocated the land for the Methodist Church Mission in 1911. This is where Kaaga Boys Secondary School stands today.

In 1908, when DC Kangangi arrived, M’Inoti was only 13. He had undergone traditional rites and was already a stickler for cultural edicts, including that forbidding boys from entering their mothers’ houses. His father had passed away when he was barely five years old.

He would later play a major role in the translation of the Bible into Kimiiru. In 1941, he was bestowed with a certificate of recognition for championing the translation of the Bible by the British Foreign Bible Society.

Philip, who had a good command of English, also tested his Kiswahili knowledge by writing his first book, Asili ya WAmiiru na Desturi Zao. This very first book written by a Meru was published in 1931.

In 1931-32, he obtained a diploma in theology and on September 29, 1932, became the first Meru Methodist Church minister.

On May 4, 1939, he bought his first car, a Ford, for the then princely sum of 1,200 shillings. He had relied on his sturdy BSA motorbike that was best suited for the cattle-trail roads of the day.

On August 28, 1948, he was appointed the Chief of Miiriga Mieru. At 55, his next door neighbour was a Mzungu DO. He built a colonial style bungalow and children were driven to and from school and his homestead guarded by fierce Alsatians.

As the Senior Chief, his flagship education project was the upgrading of Kaaga Girls School. On 15th March, 1952, Chief Biribu Kinyinga perished in a road accident. He was 57. He had been fighting traditional beer (marwa), whose imbibing was regarded as a cultural norm, and the circumcision of girls.

He was, according to the authors, “tied to the Beberu (colonialist) like the proverbial tick to a cow” and fought against the Mau Mau and thus the struggle for independence.

This book accurately showcases M’Inoti’s service to God and humanity, and his solid contributions to building the Methodist Church, schools, colleges and hospitals in Meru.