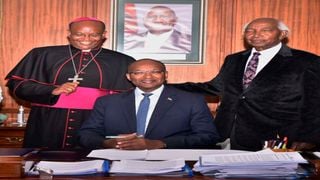

Outgoing Central Bank of Kenya Governor Patrick Njoroge (seated) with his father Mr Thomas Ngugi and siblings Archbishop Anthony Muheria and Ms Joyce Ngugi at CBK offices in Nairobi on June 8, 2023.

| PoolBusiness

Premium

Patrick Njoroge: Pious man who stared down banks and tycoons in mixed reign at CBK

Over the past eight years, outgoing Central Bank boss Patrick Njoroge’s mien has morphed from an affable smile into a sharp, penetrating glare.

Since June 19, 2015, when Dr Njoroge was appointed the Governor of the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK), some of the individuals he was to oversee, and was thus supposed to maintain an arms-length relationship with, suddenly became his enemies.

He leaves office having consigned bankers, traders, analysts and financial journalists into his fabled black book.

The book’s new entrants include manufacturers who dared tell the media that the country had a shortage of dollars.

His suspicions, or paranoia if you like, might not be entirely unjustified.

Dr Njoroge defied the directives of two presidents — Uhuru Kenyatta and his successor William Ruto — to relax stringent anti-money laundering rules that require banks to vet transactions involving Sh1 million ($10,000) and above.

When MPs threatened to veto the renewal of his term for failure to relax these rules, he laughed off the threats, noting that he would not lose a night’s sleep over failure to extend his term.

Although he remained mute on the directive from then-President Kenyatta, his words to the legislators were unequivocal: The country could not afford to relent in the effort to safeguard its financial system from potential and actual attacks.

Kenya, Njoroge told the legislators, who were scheming to change these irritable rules that had made their trips to banking halls embarrassing, would be ostracised by the rest of the world for being a haven for criminals.

“The effect would dwarf that of the Goldenberg scandal, with its record inflation and triple-digit decline in the value of the Kenya shilling,” Njoroge told MPs.

Head held high

To his credit, Dr Njoroge, an adherent of the Catholic Church’s order of Opus Dei, is walking away with his head held high.

Whereas most of his predecessors were either kicked out halfway through their first or second terms or implicated in some scandal, Njoroge leaves the corner office of CBK untarnished.

Central Bank of Kenya Governor Patrick Njoroge during the KCB Group transaction agreement documents exchange event following the acquisition of shares in DRC-Based Trust Merchant Bank (TMB), at the Nairobi Serena on December 19, 2022.

Yet, after eight years, the man who enthralled Kenyans with his piety and frugality, telling MPs that he owned no property and donated all his salaries to the church, leaves the corner office somewhat unpopular.

His perceived enemies have, however, weaved a narrative that under his watch, Kenya experienced one of its worst dollar shortages.

By overzealously going after the speculators, Dr Njoroge ended up inadvertently crashing the entire forex interbank market.

The exchange rate — which he made so many enemies trying to protect — has gone north.

The shilling has been on a freefall, hitting record lows every day.

It is currently exchanging at an average of 138.87 against the dollar.

Inflation, a measure of the cost of living that looks at the overall increase in consumer prices over a 12-month period, has stubbornly remained outside of the regulator’s target of between 2.5 and 7.5 per cent for 12 months.

Ensuring that prices remain stable in the economy is perhaps CBK’s primary role, though, in an earlier interview, he said their vision “goes beyond price stability and includes our wider mandate”.

As the hand of time chips away the remaining days of his stay at the helm of the apex bank, Njoroge’s grip on the reins of power at CBK has dramatically loosened.

There are rumours of insubordination by his juniors. Bankers are also reported to have fished out champagne as they count the hours to June 18.

Outgoing Central Bank of Kenya Governor Patrick Njoroge on December 1, 2022. He leaves office having consigned bankers, traders, analysts and financial journalists into his fabled black book.

For a man in transition, loss of control was inevitable. But Njoroge’s falling out with elements in the financial community, colleagues and government officials has been uniquely spectacular.

Background

Njoroge was born in Central Kenya in 1961. His father was an education officer while his mother was a teacher. This imbued in young Njoroge a passion for reading.

At Mang’u High School, where he went for his O-Level education, he loved reading the Anthology of English Literature, besides the Bible, which he said in an earlier interview greatly influenced him.

But it is not just a reading culture that his parents inculcated in him, but also discipline, respect for others and piety.

For his undergraduate degree, he wanted to do sciences, specifically electrical engineering, but eventually settled on Economics, which he thought had a wider scope in uplifting people’s lives.

In times of adversity, he said, he leans on a sense of higher purpose beyond resolving the problem or overcoming the adversity.

“For instance, seeing the millions of people whose lives will change if the problem is solved,” said Njoroge in an earlier interview.

He worked at the Ministry of Planning and National Treasury for nine years before moving to the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

He worked at the IMF in Washington for 10 years, rising to the position of deputy managing director by the time he left in 2015.

His career path had been straight and narrow.

"Crime scene"

So, when Njoroge was appointed Kenya’s ninth CBK Governor on June 19, 2015, by then-President Kenyatta he was literally thrust into a crime scene.

Outgoing Central Bank of Kenya Governor Patrick Njoroge. His perceived enemies have, however, weaved a narrative that under his watch, Kenya experienced one of its worst dollar shortages.

Tenderpreneurship was the vogue. Three months earlier, a little-known hairdresser had withdrawn more than Sh100 million in cash from a bank without security arrangements in a Sh791 million National Youth Service (NYS) scandal.

Yes, you could take such copious amounts of money in or out of a bank with little or no interrogation.

Such loads of cash also fed into a bubbly nightlife in Nairobi’s Central Business District (CBD).

Suddenly, Kenya had a burgeoning Nouveau riche that patronised high-end nightclubs, buying expensive drinks every night.

Luxurious apartments that would remain unoccupied for long sprung up in Nairobi’s suburbs.

There was a lot of dirty money flowing into and out of Kenya.

Dr Njoroge, whose thesis at the US-based Yale University was modelling the consequences of financial crises, knew the weak link was the banks.

In the early 1990s, banks had been complicit in the Goldenberg scandal in which the country lost close to 10 per cent of its gross domestic product (GDP) through the fictitious export of gold.

In other parts of the world, especially developed countries that are members of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), a global anti-money laundering watchdog, an individual could not catwalk with a bagful of cash into and out of the banking hall without answering some tough questions on the source or use of the funds.

Within nine months of Dr Njoroge’s appointment, CBK had taken over three banks – Dubai Bank, Imperial Bank and Chase Bank.

Suddenly, the soft-spoken, humble bachelor who mesmerised Kenyans by snubbing a luxurious house in Muthaiga Estate, Nairobi, for a simple communal home in Loresho, bared his fangs.

Profits obsession

The era of banks being obsessed with profits over people (customers and workers) was over.

Banks, he said, had to be factual in their books.

“The era where banks would wait for one to declare their profits, then compete to see who had the most impressive results is no more. We are now insisting on the factual representation of the results,” Dr Njoroge said in response to the re-provisioning of the National Bank and Chase Bank results that saw both financial institutions report losses, after being forced to correctly book their non-performing loans.

Outgoing Central Bank of Kenya Governor Dr Patrick Njoroge. Within nine months of Dr Njoroge’s appointment, CBK had taken over three banks – Dubai Bank, Imperial Bank and Chase Bank.

Chase Bank, unfortunately, never got to survive the new stringent rules, with the mid-sized lender suffering a bank run as a result.

Dr Njoroge never closed more banks thereafter, with CBK opting for arranged or forced marriages instead.

But the message was clear: banks had to be managed and run prudently.

Although the cash-handling rules on Sh1 million and more were part of Kenya’s anti-money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) framework, they were never domesticated through any local process.

Rather than wholesale compliance, all countries are able to work out exemptions and exceptions to any global regulations.

But Njoroge insisted that the rules be fully enforced, inflaming relations between customers and banks.

Banks, afraid of the Governor, could not stand up to him. MPs took up their grievances.

“When I received my mortgage, Barclays Bank asked me to explain where the money came from. When you sell your three camels, you are asked where the money is coming from,” the then National Assembly Majority Leader Aden Duale complained in September 2019.

That year, a flamboyant businessman was declared persona non grata by one of the local banks due to the strict implementation of Know Your Customer (KYC) rules.

The tycoon protested but Dr Njoroge stood his ground.

“As I said recently in Parliament, more than 99 per cent of bank accounts in Kenya hold less than Sh1 million, so the vast majority of customers do not even encounter this requirement.

“Even for those who do – in the course of buying and selling land or property, or a motor vehicle – most find the requirement easy to fulfil,” explained Dr Njoroge.

Selfish interests

A lesson central bankers took from the collapse of the so-called political banks in the 1990s is that they are not always started by people keen on doing clean financial business.

Shareholders could use, and some have already used, banks to line their pockets by over-lending to themselves at exceedingly low rates or circumventing other prudential guidelines.

Outgoing Central Bank of Kenya Governor Patrick Njoroge. Since June 19, 2015, when Dr Njoroge was appointed the Governor of the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK), some of the individuals he was to oversee, and was thus supposed to maintain an arms-length relationship with, suddenly became his enemies.

Dr Njoroge thought he was addressing this problem when he shut down the three banks.

Banks were slapped with cash penalties in the millions for several infractions, ranging from NYS-type scams to “speculating against the shilling”.

Financial analysts went into hibernation, and journalists found themselves in a faceoff with the governor.

It might be Dr Njoroge was pushing his opinion, rather than being pragmatic.

Those who know him say that even at CBK, it was his way or the highway.

Any whiff of resistance was met with a sledgehammer.

His failure, if you could call it that, was not necessarily the result of a flaw in character. It might have been a miscalculation.

They say the road to hell is paved with good intentions. It is true that speculation had turned the country’s foreign exchange (forex) market into a den for opportunists.

But his overzealous approach ended up weakening a platform that enabled banks to borrow dollars from each other.

He also seems to have regretted shutting mid-sized Chase Bank in April 2016, though he insists there were significant deficiencies in the bank that led to the decision to close it.

“The bank was connected with virtually every corner of the country, in terms of the people, sectors and more…. That is a decision (to close it) we did not take lightly, given its adverse impact on the population and the sector in the short term,” said Dr Njoroge.

As he was preparing for his last post-Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) briefing last week, the sad news broke out that his mother had died.

Even those who wanted to celebrate his exit must have been forced to put the champagne back.

Financial journalists expected Dr Njoroge not to attend the briefing, which would be, as it has been traditionally, a day after the MPC had sat. The briefing was to be on Tuesday last week.

Instead, the briefing was moved to Wednesday, to allow Dr Njoroge to attend his mother’s burial on Tuesday.

Asked when he would leave office, Njoroge responded, rather gravely, “I am still working.”