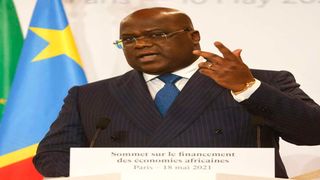

President of Congo Democratic Republic Felix Tshisekedi.

| File | AFPOur Columnists

Premium

EAC fever looms as Congo votes

Congo, the land of fevers. Gold fever. Coltan fever. Ebola fever. And, certainly, a burning election fever—President Felix Tshisekedi is comparing his Rwandan counterpart to Adolf Hitler, no less, in heated campaign speeches—and when it breaks, there might be quite a mess, I’m afraid.

DRC is a fascinating place for someone like me seeking post-sabbatical relevance and a rich beat to report on. Hanging out with Congolese exile types left me worried that DRC could soon become a Big-Power flashpoint.

Congolese elections are big tomatoes; it is a country of 100 million people; so, at the last election, 40 million voters were registered, with 700 political parties, 16,000 parliamentary candidates, in a vast territory with poor communication.

Then there is the fever of rebellion brewing, particularly in the East. Unhappy opposition groups have been complaining that although election officials have allegedly spent $1 billion on preparedness, equipment and materials are still in China and South Korea, only days to the election.

Some argue that President Tshisekedi is not really interested in a free and fair election. They accuse him of loading the dice by putting his relatives in all the institutions that are critical for determining the outcome: The electoral commission, the military, Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Education and so on.

The more cynical ones think that the President just wants results from a few parishes and he will use those to declare victory and continue ruling. Apparently, only 27 per cent of eligible voters are on the roll which the government has not allowed the opposition to inspect.

There are also complaints that voters from Swahili-speaking communities are not being registered. Some sections of Congolese society see Swahili speakers as “foreigners”; a difficult concept since anywhere between 40 and 70 per cent of Congolese speak it and it’s one of the national languages.

DRC is generally not strong on elections. The 2018 one was a mess—it was well organised from a technical point of view; the man who organised it, Corneille Nangaa, is an expert who has done elections all over Africa. But the result of that election has become like the assassination of JF Kennedy. A suspect, Lee Oswald, was arrested, accused and assassinated. But people are still looking for the killer, years later.

Felix Tshisekedi was declared winner by the electoral commission and confirmed by the High Court, sworn in and is governing. The Congolese I have spoke to, especially those who do not like President Tshisekedi find the concept laughable. Of course Martin Fayulu, the former oil executive, won by 62 per cent of the vote, they say. The President only got 22 per cent and Emmanuel Shadary 17 per cent.

Asked for a meeting

Assuming, even for a second, that this was the case, the process by which the President won by 38 per cent, with Mr Fayulu 34 per cent and Mr Shadary 23 per cent, is, of course, a great mystery the Grassy Knoll crystal ball gazers of the Congo haven’t quite explained.

There is credible information, however, that after the election and before the results were announced, then-President Joseph Kabila asked for a meeting with Mr Fayulu. At the time, Mr Kabila controlled a little bit more than just his white beard: He had been in power for 18 years, he controlled the army and, to a large extent, the government machinery.

During the campaigns, Mr Fayulu exuberantly enumerated the people he would jail. Topping the list was Mr Kabila and his generals. Mr Kabila wanted an agreement that Mr Fayulu would leave him, his family and generals alone and that he would agree to co-habit politically since the retiring President had control of Parliament.

Mr Fayulu would allegedly hear none of it: “Bring Kabila to me!” he cried. “I’m the President, I cannot go to see him.” And he was going to ride Kabila and his general horsey from Lubumbashi to Kisangani before throwing them in the cooler and slap the mineral companies with taxes while at it. I fictionalise and dramatise, of course, but I was told before Mr Fayulu knew what was happening, Mr Tshisekedi was President with agreements guaranteed by Egypt, Kenya and South Africa.

My new Congolese friends tell me that Mr Fayulu didn’t do well under his own steam; the real magician propelling him was Mr Moise Katumbi Chapwe, a wealthy baron who couldn’t contest because he was in exile with a three-year jail sentence.

Mr Katumbi is running in next week’s election, after Mr Tshisekedi tried to bar him, claiming he was Zambian, not Congolese. Mr Fayulu is also in the race, although he not expected to repeat his earlier success.

Mr Tshisekedi will win. The East might rebel. Mr Tshisekedi might invite the South Africans for help. The South Africans might ask their Kremlin friends for help and Wagner Group boots might flood the Congo. And the Wagner Group might say: Why spit this juicy morsel? And they might take the country for themselves and use it as a resource slave. And the East African Community will catch the war fever.

Congo, the land of fevers.

- Mr Mathiu is a media consultant at Steward-Africa and former Editor-in-Chief of Nation Media Group. [email protected].