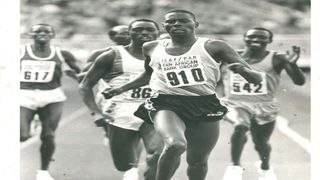

Olympic champion and world indoor record holder Paul Ereng' charges to victory ahead of world champion Billy Konchellah (86) in the final of the 800m at Moi International Sports Centre, Kasarani.

| File | Nation Media GroupTalkUP!

Premium

Remembering student sports superstars of the 1980s

What you need to know:

- Kakamega High, one of Kenya’s oldest schools, produced a galaxy of stars. Its legendary principal, the late Gaylord Avedi, sought to do his best in exploiting talent at his disposal

- Ereng’, a student at Starehe Boys Centre, took the achievements of Kenya’s student sports superstar to the highest point when he powered his way to the 800m Olympic gold medal in 1988.

- Some of Kenya football’s most iconic footballers first made their names as schoolboy prodigies: Sammy Owino, Nashon Oluoch, Joe Masiga and William Obwaka.

- Obwaka attended Starehe, Masiga Nairobi School, Oluoch Highway Secondary and Owino Technical High. All juggled football and their studies to become university graduates.

When he powered his way to the 800 metres Olympic gold medal in 1988, Paul Ereng’ did not just soothe the spirits of compatriots battered by the divisive queue-voting election that triggered the unrelenting and often violent push for multi-party democracy in Kenya.

He took the achievements of Kenya’s student sports superstar, a common feature in the country’s amateur sport, to the highest point in international competition.

Ereng’ was a student at Starehe Boys Centre. The fervent support of every boy who was in the school that year must have travelled 10,000 kilometres to push him over the finish line in that unforgettable 1minute and 43.55 seconds.

Athletes compete in a past race.

They felt an intimate ownership of his gold medal and in a profound sense it actually belonged to them for Ereng and his schoolmates were one spirit in many bodies. Thirty two years on, the sentiment is almost as strong.

In most of the 1980s decade, the schoolboy superstar was a dominating feature of Kenya sport, especially football. Local football clubs filled the stadiums in much the same way as Tanzanian and Ethiopian clubs do today.

And across their ranks, from title contenders to their escorts, schoolboys enthralled us. In fact, one very delightful team of the early 80s, Ministry of Works, Kakamega, was almost exclusively made up of boys from Kakamega High School.

When the boys left school, they made a natural progression to their final destination – AFC Leopards. It was the same story to a lesser degree with Kisumu Hot Stars and Gor Mahia.

Why the Kakamega High School-MoW-AFC Leopards triumvirate never blossomed into a mighty club like Egypt’s Al Ahly is one of the great failures of Kenya football management.

All the raw materials were – and remain - in place but process is non-existent.

Oldest schools

Kakamega High School is one of Kenya’s oldest schools. Its legendary principal, the late Gaylord Avedi, gave Kenya a galaxy of schoolboy stars. He was a focused man who sought to do his best in exploiting the talent at his disposal.

After losing the national school’s football title to Njoro High School in 1977, Avedi embarked on a comeback mission. He re-kitted his charges with a flowing green uniform – including green coloured boots. This gave rise to the famous nickname, Green Commandoes.

The highly motivational teacher inspired his team to win back-to -back national titles between 1979 and 1982. The captain of the team at that time was Peter Lichungu, later to become a mainstay of the AFC Leopards defence.

He was in impressive company. Peter Ouma, Mike Amwayi, Peter Zimbo, Joseph Mukatia, Ronnie Watsiera, George Nyangi Odembo, Dan Musuku and Patrick Shilasi, all of whom would later become household names for Leopards and Gor Mahia, were in the Green Commandoes squad.

And in Chris Makokha, Avedi had an excellent technical man. This mathematics and physics teacher would go so far as to coach Harambee Stars.

Of course, good teams need good rivals to thrive. Even at the height of its powers, Kakamega High School drove with one eye firmly trained on the rear view mirror because of the hungry rivals in its wake: Musingu High, Kamusinga Boys, Chewoyet High, Upper Hill, Khamis High, Jamhuri High, Alidina Visram, Kisumu Boys, Njoro Boys and Iterio High.

Some of Kenya football’s most iconic footballers first made their names as schoolboy prodigies: Sammy Owino, Nashon Oluoch, Joe Masiga and William Obwaka.

Obwaka attended Starehe, Masiga Nairobi School, Oluoch Highway Secondary and Owino Technical High. All juggled football and their studies to become university graduates.

Oluoch and Owino were key members of the Gor Mahia team that reached the 1979 Africa Cup Winners Cup final. The scout that Canon sent to spy on their prospective opponents before that final must either have missed their sterling performances or Theophile Abega, the charismatic Canon and Indomitable Lions captain, was pulling Allan Thigo’s leg, going by the question he asked the Gor Mahia player-coach after the final.

Beaten convincingly

While waiting for their connecting flights home at Lagos Airport after winning their respective semi-finals – Gor Mahia against Guinea’s Horoya and Canon against Nigeria’s Bendel Insurance – Abega complimented Thigo on a job well done. “We expected to face Horoya,” he told him, “but you have beaten them convincingly. You have earned your place and we respect you.”

For good measure, Abega let Thigo know that Canon had somebody watching both legs of their semi-finals.

But after the 6-0 drubbing in Yaoundé – 8-0 in aggregate – the same Abega, with affected annoyance, asked Thigo: “Why did you bring us schoolboys to play with us? What did you expect them to do?” The players Abega was referring to were Owino and Oluoch. Actually, they were not schoolboys then; they had cleared their “A” Levels the previous year and were waiting to go to university.

Make no mistake, though: those boys were good. To this day, they remain – at least to my mind – the best the club has produced in their respective positions. Their departure, both of them to the United States of America, dealt the team a great blow and it is testament to its depth that it remained a contender for an African title, eventually winning one in 1987.

As to what happened to that depth, I am at a loss. What I know for a fact is that Gor Mahia’s disappearance from the African football radar is a matter of deep regret and more so for the great opponents it once terrorised. The team is missed.

Lost year

Just as it has severely disrupted the school academic programme rendering 2020 practically a lost year, Covid-19 has decimated the sports calendar. Spare a thought for the stars of all disciplines who have seen their hopes of actualising themselves disappear in a painfully unfolding slow motion fashion.

Nobody really knows if and when there will be a return to normalcy. Students whose disciplines are age group-bound have suffered the most.

Once upon a time, our sports reports were dominated by the heroics of student superstars.

Close behind them were coaches and principals we continuously had to interview, great and good men like Brother Colm O’Connell of St Patrick’s Iten and Eliud Wasonga of Starehe Boys Centre. We are living through truly bleak times and we must muster all the strength to hope and to believe so that we can stay the course.

If 2020 is lost, there very well could be a cascading effect and a huge portion of 2021 will be lost as well. If ever the staying power quality of sport was needed, that time is now with tragic deaths being reported from our schools. That is why it feels good to remember some glorious times of years gone by.

Kisumu Day and Western Stima's Benson Omala lifts his trophy on January 29, 2020 after he was named the Kenyan Premier League Player of the Month for December 2019 at Kisumu Day.

***** ***** ******

To everybody who sent me compliments on this column’s 10th anniversary, thank you. And to all those who requested me to include more excerpts from the past and even specified the pieces they wanted, well, every party has to come to an end. But we are on the same page; I enjoyed the recollections as much as you did and I think we can agree to wrap it up by meeting part of the way.

When a post-Covid world returns to stability, touch wood, who knows, another book could be coming your way. Kick-Off did. Ebalu did. And the stories that appear in this column, inspired by your continuous patronage, might one day be read in book form. So here we go:

The 10 most memorable quotes in the world of sports: Published on Saturday, July 22, 2017.

“I spent 90 per cent of my money on women and drink. The rest I wasted.” George Best.

An alcoholic lives in an alternative universe and George Best was not any different. He was one of the world’s greatest footballers who only never played at the World Cup because he was a world apart from his pedestrian Northern Irish countrymen. Best blew his huge fortune and the quote above is how he described it.

“I quit school in the sixth grade because of pneumonia. Not because I had it, but because I couldn’t spell it.” Thomas Rocco Barbella

Barbella, better known as Rocky Graziano, was an honest man, as this plain speaking shows.

Considered one of the greatest knockout specialists in boxing history, Graziano was once the world middleweight champion. In 1955, he released a biography titled “Somebody Up There Likes Me.” It documented his turbulent life and was the subject of an Oscar-winning film of the same title.

Superb Zarika defended her title, so let’s interrogate language of boxing: Published on Saturday, December 9, 2017.

Shadow boxing: Muhammad Ali once quipped: “I saw George Foreman shadow boxing. The shadow won.” Only he could witness such a phenomenon. Shadow boxing is fighting with an imaginary opponent in training but in ordinary life it refers to making a show of dealing with a problem while actually avoiding it.

Punching bag: This is a vital tool in a boxer’s training kit. It is heavy and is usually hung in a corner of the gym. It is filled with sand or saw dust. Boxers pound it to exhaustion.

Figuratively, anybody who suffers a similar fate in being used by others to vent their anger and frustration is called a punching bag.

The double life and tragic end of legendary football star Daniel Nicodemus ‘Arudhi’: Published on Saturday, February 24, 2018

One day, on his way to Starehe Boys Centre where he was an assistant director, Patrick Shaw, the mountainous crime buster of the 1970s, passed by Kariokor Market. Thereafter, word swept through the team that he had told Salome: ‘Tell your boy to stop what he is doing or else I will stop him.’

Shaw was a police reservist who operated by his own rules, a system within a system. He was so famous for issuing such warnings to the many criminals that he later executed in cold blood that this statement is eminently plausible.

It was thus only a matter of time before Nicodemus made his rendezvous with death. On the night of June 22, 1981, his bullet-riddled body was dumped on a slab at the City Mortuary. They buried him in his native village at Alego Ng’iya.

Luo Union's Daniel Nicodemus out jumps “The Callies” defence during a friendly match in Nairobi. Nicodemus, a football star and notorious criminal, scored three goals in this match.

Of his team mates, only his best friend, William Chege Ouma, attended the funeral. The rest were too scared of Shaw’s dreadful habit: he went to the funerals of his victims to scan the mourners using the common sense logic that funerals are attended only by a deceased person’s closest people.

Nicodemus’ team mates were apprehensive that Shaw might pounce on somebody.

Roy Gachuhi, a former Nation Media Group sports reporter, is a writer with The Content House. [email protected]