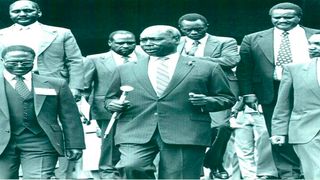

President Daniel Arap Moi (centre) leaves Kenyatta International Convention Centre at the height of Kanu rule. With him is Cabinet secretary Henry Kosgey (right) and the head of the Seventh Day Adventist, Pastor Wangai (left).

News

Premium

Yippee! Kanu turns 61, but what is there to celebrate about our political parties?

What you need to know:

- In 1986, President Daniel Arap Moi declared that the party was above government, Judiciary and Parliament.

- When the final history of Kanu is written, it will be about intrigues, murder, mayhem and plunder.

The former ruling party Kanu this week turned 61 albeit without ballyhoo. And since a chief had once forced me to pay for Kanu membership, in exchange for my identity card, let me celebrate the party that later became the citadel of arrogance and hubris – until it was humbled at the ballot box.

Somehow, Kanu has survived – most likely as a political lesson to the current fly-by-night parties that have littered our terrain; many of them offshoots of the Kanu bad manners. Kanu is no longer the boisterous party of yesteryears and with only two elected senators, it seems to have lost its allure, the signature sickle feathers.

During its halcyon days, Kanu’s anthem, “Oh, Oh, Kanu yajenga nchi”, became the Voice of Kenya (and later KBC) news signature tune and this went on until the dawn of plural politics. Kanu had also grown horns, to an extent that in 1986, President Moi declared that the party was above government, Judiciary and Parliament. The only party whose symbol and colours were included in the Coat of Arms and in the national flag; a Jogoo House and a Jogoo Road in the City.

Kanu also had a powerful disciplinary committee that was composed of party hawks, David Okiki Omayo, Kariuki Chotara, Burudi Nabwera, Sharif Nassir, Nathan Munoko, and James Njiru, which dealt with, many a times, flimsy accusations against members. It was during this period that Moi had created the ministry of National Guidance and Political Affairs with Njiru as the minister and that is how he, Mr Njiru, got the guts of summoning vice-president, Dr Josephat Karanja, whose loyalty to Kanu was doubted. Better put, his time was up.

A story is told of how one day, Moi had a rally in Kerugoya Stadium and he decided to fly back. Mr Njiru, by then a powerful politico, decided to board the President’s limousine and on reaching Ngurubani market, he addressed a crowd that had initially thought it was Moi on board. Bad bet.

The next morning, Mr Njiru, known for his high-pitched Kanu motto sloganeering, was summoned to State House Nairobi and was accused of plotting to take over the government. “I told mzee I had not even imagined taking over his government,” he would later recall about the mistake that led to his downfall.

“In politics,” observed 19th century French leader Napoleon Bonaparte, “Stupidity is not a handicap.” It seems that Kanu stuck to that view by shooting its own foot, damaging its membership, credentials and ignoring its foundation as a nationalist party; largely united by fear and political interests.

Cold war mischief

When the final history of Kanu is written, it will be about intrigues, murder, mayhem and plunder. It will also be about a political party that amalgamated various political interests in order to win independence and which brought together the best brains in the country. Luckily, it had the backing of Jomo Kenyatta, who was more of a pan-Africanist having hobnobbed with the best in the push to end colonial rule in the world. Again, Jomo had returned from jail to find politicians divided into either Kanu or Kadu – with each jostling for his attention. But Kanu, whose one-finger salute stood for one nation, won the day since Kenyatta was convinced that the majimbo system propagated by white settlers and Kadu would divide the country.

But deep inside the formation of Kanu was the fight between Jaramogi Oginga Odinga and trade unionist Tom Mboya for the control of Kenyan politics. By then, Mr Mboya had been identified by the West as the good man for Africa. On the other hand, Jaramogi was being dismissed for his dalliance with the Red states – a man who was to be kept away from the moderates. But, give it to him, Jaramogi was ahead of everyone.

Out of the cold war mischief and the British fear on the future of its settlers was the future of Jomo Kenyatta. While most of the moderates did not want to link Kenyatta’s release to the political progress towards independence, it was Jaramogi who started the Kanu campaign that linked Kenyatta’s release to self-rule. That way, he had boxed the moderates into a corner and tamed their ambitions. If Kenyatta was not released, and that seemed to be Jaramogi’s secret reasoning, Mr Mboya and James Gichuru would have an upper hand over him.

What we know today from declassified British Cabinet papers was that Prime Minister Harold Macmillan had agreed that Kenyatta should never rise to become Kenya’s leader and it was felt that eyes were either on Mr Mboya or Mr Gichuru.

The British had a problem with Mr Odinga because of his links to the Eastern bloc. The Mi5 had intercepted tens of Mr Odinga’s letters which are now in file KV2/40 at the British archives. Mr Odinga describes the 1960s period as “difficulty” in his autobiography because of “concerted world press campaign to elevate Mr Mboya to the unchallenged leadership of Kenya Africans”. That is why he plotted to outsmart Mboya with the formation of Kanu.

That plot had started in 1960 in Dr Julius Gikonyo Kiano’s house in Riruta, Nairobi, where a meeting was called for all elected leaders with the aim of launching one national party. The meeting, called by Mr Odinga, had agreed that they would register what was to be known as Uhuru party for tactical reasons. With the fear that the colonial government might not register a nationwide party, they had agreed that they would later change its name to Kanu (Kenya African National Union).

Launch of the party

Those who attended the meeting included Mr Gichuru, Arthur Ochwanda, Dr Kiano and Argwings-Kodhek. Interestingly, Mr Mboya only came to learn about the meeting when a journalist took to him a photocopy of the signed agreement.

“Has Dr Kiano signed?” asked Mr Mboya of the man he had organised the airlifts with. On the signed agreement, Dr Kiano was number one.

That meeting was significant on the future of Kanu: “The meaning of Odinga’s plan was patent: It was to shut Mboya out from any position of leadership in the main organ of Kenya nationalism,” wrote Mboya’s biographer David Goldsworthy in the book, The man Kenya wanted to forget.

And when the time came to launch the party on May 14, 1960, the meeting was taken to Limuru since the likes of Jaramogi feared that the rivalry between Mr Mboya’s Nairobi People’s Convention Party and Argwings-Kodhek’s Nairobi African District Congress would mar the event. If Mboya boycotted that meeting, he would have been locked out and Mr Odinga had, two days to the meeting, released a list of Uhuru Party officials which had Ronald Ngala, Jeremiah Nyagah, and Gichuru. But the list was denounced by Ngala and Nyagah while Mr Gichuru said he had been misled by Mr Odinga. What was worrying them was the exclusion of Mboya. According to the Mboya biographer, this was “an important breakthrough for Mboya; at least a few of the conspirators were having second thoughts about the wisdom of trying to keep him out.”

Jaramogi was claiming that Mboya “was interested in his own ascendancy to power” by using his “unlimited supplies of foreign money”. But Jaramogi, too, was not a clean man and relied on Eastern Europe financiers who were determined to have their man in power.

And that is how Kanu was born, in acrimony and backstabbing, and it became a platform on which various interests and egos were pursued.

Its survival as a nationalist party, especially in the 60s, depended on how Mboya, Odinga and the Kiambu group perceived power. In the 70s, the party was more or less dead frightened that if it conducted party elections, a new crop of leaders would emerge to challenge those who had lined up for the Kenyatta succession. And as Kenyatta’s health started deteriorating in mid 60s, a meeting was called in Kiambu to dilute Mr Odinga’s powers. Mr Moi and Mr Mboya handpicked delegates for this conference and Mr Odinga saw the plot and left to form his own Kenya Peoples Union.

'Baba na mama'

With his ouster, a reckless Kanu run amok and it culminated with the assassination of Mr Mboya in July 1969, proscription of KPU and detention of its members, and the assassination of JM Kariuki, the socialite millionaire-turned government critic.

In 1975, when Shikuku alleged in Parliament that there was an attempt to kill the House the way Kanu was killed, he was arrested and detained without trial. And so was Jean Marie Seroney, the temporary speaker, who shot down vice-president Daniel arap Moi’s attempt to have Mr Shikuku substantiate. “You don’t substantiate the obvious,” Moi was told by the Speaker. Seroney was too detained.

It was the same script that Kanu followed from 1978 when it touted itself as 'baba na mama' – and elevated its place in Kenya as the highest policy making organ. That is what Peter Oloo Aringo once said.

That’s how Kanu lived by the sword. It also became corrupt, inept and careless. Finally, when Moi attempted to managed his succession by handpicking Uhuru Kenyatta, he ended up blowing up the party after Raila Odinga left with most of the veterans.

Fast-forward to 2021 and Baringo Gideon Moi is in-charge of the shell that remained. But the truth is that most of the political parties in Kenya have the split image of Kanu – simply because they are founded to mesmerise the crowds with promises while, at the bottom, they represent leadership wars.

And that should be the take home for the electorate – you are being conned. The season of politicians taking tea in your local kiosk and eating mandazi is approaching.

Meanwhile, happy belated birthday Kanu. Your children have mastered the art.

[email protected] @johnkamau1