Why Taliban rise may be China’s opportunity

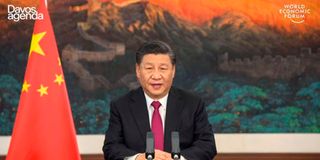

This video grab taken on January 25, 2021, from the website of the World Economic Forum shows China's President Xi Jinping speaking from Pekin as he opens an all-virtual World Economic Forum, which usually takes place in Davos, Switzerland.

The Taliban, the new rulers of Afghanistan, may be receiving anxious responses around the world, with many calling on the group to choose formal political leadership rather than stick to archaic components of the Sharia law.

But this crisis may be just what China needs to win over new friends in Afghanistan, observers say, taking advantage of its wide network in the region.

On Saturday, for example, the African-Caribbean group at the UN Security Council, known as the A3+1, issued a rallying call for “sustained efforts to embrace peace, cease links to terror groups and engage in meaningful dialogue” with all stakeholders in Afghanistan.

The A3+1, which includes Kenya, Tunisia, Niger and the Caribbean island nation of St Vincent and Grenadines, says that search for peace must include human rights, “particularly those of the women, youth and ethnic minority groups".

These calls were also made by UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres, who also cited the growing humanitarian crisis in Afghanistan and asked for a direct engagement with the Taliban.

Ever since the Taliban stormed the capital, Kabul, as US and allied forces left the Asian country, the number of those in danger of starving has increased.

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi gestures to journalists before a National People's Congress press conference in Beijing on March 8, 2016.

"Perfect partner"

In a fresh appeal for aid last week, the UN aid at least 18.4 million people are in need of humanitarian assistance, while one in three people are facing food insecurity in a country where more than half of children under five face acute malnourishment.

This crisis though may present Beijing with an opportunity to outdo the West, whose NATO military coalition left Afghanistan last month after two decades of war, to China’s advantage in the long-run.

After the Taliban stormed Kabul, Beijing decided not to close its embassy, alongside Russia and Pakistan.

The decision may have been a result of behind-the-scenes contacts with the Taliban and an assurance of protection.

On July 28, for instance, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi met with Mullah Abdul Ghani Bardar in Tianjin, becoming the first senior official to publicly meet with the Taliban, outside of the Qatar mediation circles.

“In some ways, Afghanistan under the Taliban is China’s perfect partner: dysfunctional, dependent, and happy with whatever China can do for it,” Ian Johnson, an expert at the Council on Foreign Relations, an American think-tank, observed in a recent analysis.

“China’s goal is likely to be at least as much political as economic. Beijing aims to head off any potential support for Muslims in Xinjiang that could come from Afghanistan.

“And perhaps most importantly, China’s engagement in Afghanistan can show other countries how China supports regimes: with few questions asked as long as they support Chinese interests.”

Foreign mission

In 1996, as the Taliban stormed Kabul with their brutality, Beijing had been among the foreign missions to close shop.

The Taliban, then an offshoot of US-supported militia against the Soviets, had risen to power by committing such brutal acts such as assassinating a President who had fled into a UN compound.

This time, Beijing chose to remain, which Johnson thinks reflects China’s view that Western powers have been psychologically weakened as shown in the way they chaotically fled Kabul.

So how will Beijing engage the Taliban?

One way, China expert Yun Sun, a Senior Fellow at the Stimson Centre, a US think-tank, thinks Beijing will be realistic. China has not given formal recognition to the Taliban, but has suggested it is the genuine organisation to deal with.

“They (Chinese authorities) think in the past 20 years, the Taliban has moderated and is now more pragmatic and practical,” she said. The Taliban was weak the last time they took power in 1996, she argued, adding that Beijing may have had little need.

Today, with China’s ever-expanding need for trade routes, and the ambitious Belt and Road Initiative, Afghanistan and whoever leads will be useful to China.

The relationship though may be only partially business-oriented.

“China will seek to revive business ventures inside Afghanistan, which the Taliban is likely to support because investment will provide badly needed revenues,” Johnson wrote in a Council on Foreign Relations bulletin.

“The Afghan economy is fragile and highly dependent on Western donors’ foreign aid, which will almost certainly be cut off, so any sort of investment, especially if it is not accompanied by lectures on human rights, will be welcome.”

In this picture taken on September 11, 2021, Taliban fighters sit in the greenhouse yard at the home of the Afghan warlord Abdul Rashid Dostum in the Sherpur neighborhood of Kabul.

Frozen reserves

The US froze $9.5 billion in Afghanistan reserves as the Taliban took over and it is unlikely the $500 million funding initially scheduled for disbursement will be released unless there is certainty.

That analysis also argued that Afghanistan is attractive to China because the Taliban do not subscribe to a Western-style democracy with its incessant demands for civil liberties. That means the Taliban will not criticise China’s treatment of Uyghurs and other Muslim minorities in Xinjiang, as the West has done.

As opposed to the Taliban which imposes a strict sense of Sharia, including on dress-codes that demand women must be covered fully and men keep beards, China runs subtle policies on keeping long beards, wearing veils and the loud recital of prayers.

Beijing has argued its controversial re-education programmes are counter-terrorism measures. Engaging the Taliban may forestall any future exportation of extremism into China. In exchange, the Taliban may also sit steady knowing Beijing will not lampoon the group’s human rights record.

At a gathering of foreign ministers from Afghanistan’s neighbouring countries, Mr Wang told the audience Beijing would be willing to support the Taliban to fight the pandemic, control borders and refugees, and fight terrorism and drug trafficking. Apart from China, Afghanistan borders Iran, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan.

“As neighbours who share a border with Afghanistan, we are more eager than anyone else to see Afghanistan get out of war and chaos, and resume peace and development, Zhao Lijian, China’s Foreign Ministry Spokesman said on Friday in his weekly press briefing.

“There is no military solution to the Afghan issue. We call on the Afghan side to form an open and inclusive political structure, practice moderate and sound internal and external policies, adopt friendly policies towards its neighbours abd make a clean break with all terrorist organisations.”

Despite having fewer resources, Afghanistan may offer a lucrative route for China’s BRT as it could help it escape competition with rivals India, US, Japan and Australia. If Afghanistan can steady, China could reach Iran and Turkey and into the sea routes without a sweat.