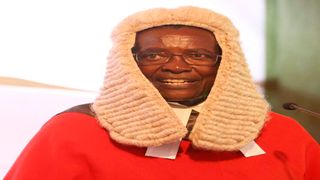

Former Chief Justice David Kenani Maraga.

| File | Nation Media GroupNews

Premium

Ahmednasir Abdullahi: Why Maraga was least qualified for Chief Justice job

In a country that celebrates mediocrity and settling for the second fiddle is the norm when it comes to employing heads of key institutions, Justice David Maraga was in good company when he was tapped by the Judicial Service Commission (JSC) to be Kenya’s 14th Chief Justice since independence and the second under the 2010 Constitution.

Kenya naturally gravitates towards the uninspiring and the average and has an enduring aversion to its more qualified men and women. This aversion to excellence is evident even when State corporations or constitutional commissions undertake what looks like an open and competitive process but end up with the least qualified. For a country run by the least qualified, Justice Maraga was inducted into an elite and revered company.

Brought little to the office

Apart from fleeting ambition for the job and a disarming smile, Justice Maraga brought little to the office. He had no charisma, was not a highly regarded judge, nor was he considered an erudite scholar or a seasoned legal eagle in his days in private practice. If the word average is apt in describing someone holistically and without leaving anything to the imagination or conjecture, it fits so perfectly into the tall frame that is Justice Maraga.

When Justice Maraga was appointed Chief Justice in October 2016, few outside the legal profession had ever heard of him. Kenyans, nonetheless, welcomed to the office a judge of unknown qualities and character.

Few expected him to have the towering intellect, rich and diverse background of his immediate predecessor, but to be fair, he didn’t even come close the disciplined and fearsome reputation Bernard Chunga brought to the job. Nor the wisdom, honesty and simplicity of Justice Abdul Majid Cockar. Justice Maraga was a lucky guy, he gambled that by sheer chance the Judicial Service Commission would give him the job. And it did!

As Shakespeare wrote in his play, The Twelfth Night, “In my stars I am above thee; but be not afraid of greatness. Some are born great, some achieve greatness, and some have greatness thrust upon ‘em”.

Past career

Greatness was thrust upon Justice Maraga, probably with meek, shy protestation. Nothing in his past career as a judge of the High Court and the Court of Appeal, or even as legal private practitioner litigating the odd debt collection case or the routine cases in Nakuru, prepared Justice Maraga for the office of the Chief Justice.

Two cases he handled as a High Court judge provide a good snapshot of Justice Maraga’s limitations as a jurist, and strength as a politician. The first involved a murder case where one Andrew Mueche Omwenga killed a woman and her lover. In his judgment Justice Maraga muddles up the basic principle of criminal law and makes a tasteless mixed grill of legal principles, ranging from provocation, self-defence, temporary loss of control, and then acquits the accused, the overwhelming evidence to the contrary notwithstanding. This case has troubled and defined Justice Maraga’s tenure in a number of ways. This is a judgment that has variously been condemned.

Post-election violence

The post-election violence and the burning of a church in Eldoret case, involving one Steve Leting and others, shows, again, Justice Maraga’s inability or unwillingness to lucidly apply the law, the consequences notwithstanding. He makes so many excuses and polemical statements in his judgment justifying the decision to acquit the accused, that it makes one wonder why he decided to listen to the case.

Justice Maraga may never have been appointed CJ. He was lucky to be interviewed by a JSC panel including Prof Githu Muigai, Justice Mohamed Warsame, Justice Aggrey Muchelule, Prof Tom Ojienda and State functionaries.

He was, but a beneficiary of a scheme that was more interested in stopping more qualified candidates than ensuring the best candidate gets the job. The more qualified candidates were victims of a predetermined marking scheme that ensured they simply did not have a chance to get the job. The interview was probably more about who should be stopped, rather than who was the best qualified.

The JSC panel was simply too scared to contemplate that the more qualified candidates in the likes of Prof Makau Mutua, Dr Smokin Wanjala or even Nzamba Kitonga would win the position. These are towering intellectuals in their own rights. Makau and Wanjala are Ivy League law graduates who taught for well over 25 years and are well regarded in the academia. They are scholars who have published books and articles on a wide range of topics. Kitonga practised law at the highest level. As a former chairman of the Law Society of Kenya and chair of the Committee of Experts that wrote the Constitution, he had exposure and insight of law. Any one of them was qualified to take up the job and propel the Judiciary to a new level.

Ethnic fault lines

The JSC members are drawn from interest groups and are connected to competing power grids. It is a powerful commission that has control over the Judiciary. JSC members are usually polarised along certain political and ethnic fault lines and it is not unusual for certain groups to have a predetermined favourite candidate or to be given instructions by those in power that certain candidates are red lines not to be crossed.

The politicisation of the JSC was principally brought about by the Jubilee administration, unlike the Kibaki one that give it a wide latitude and independence, President Kenyatta’s administration is obsessively preoccupied with controlling the JSC. It variously reshuffled the two representatives of the public and takes interest when judges and lawyers elect their representatives. Current JSC members are considered to be subservient to the interests of the government.

Since Justice Maraga was not a front runner and was not seen as a serious candidate, few bothered to interrogate him deeply. In the end he emerged the top, just because the better candidates were blocked by the competing interests within the JSC.

Checks and balances

With the JSC about to recruit Justice Maraga’s successor, it is imperative to ensure that the process has checks and balances and is subjected to verifiable transparency. Schemes where candidates are graded 98 or 99 per cent by five or six commissioners as part of a prearranged pact must be brought to an end. Only in lower primary school classes and JSC interviews do candidates score 99 per cent. The former is merited, the latter is a scheme that irredeemably taints the JSC process.

So, when Justice Maraga, adorned in full regalia of an English chief justice, entered State House, he was welcomed with high fives by President Kenyatta and his handlers. Tired of Dr Willy Mutunga’s assertive position that the Judiciary is a co-equal arm of government, and fed up with the Judiciary’s robust protection and enforcement of the nascent Constitution, Mr Kenyatta and his handlers were sold to Maraga as a Chief Justice that they can do business with. Being a judge, few knew what he stood for.

President Kenyatta was sold the idea that Maraga did not have the baggage of activism and agitation for reforms, nor did he have the gravitas and public profile Justice Mutunga had. President Kenyatta was told Justice Maraga was the quintessential establishment judge of yesterday, without any baggage as a reformist. Little did Mr Kenyatta and his men know that Justice Maraga would pose the greatest challenge to his government.

Justice Maraga’s tenure is essentially defined by his relationship with the President. He was initially welcomed by the Kenyatta administration, but the relationship went downhill quickly. Principally, a mutual shared apathy between the two led to a deterioration of the relationship.

Justice Maraga towering over hundreds of school children waiting patiently for his chance to greet the President in a public rally under the scorching sun was an early sign of the good chemistry between the two before the relationship hit the rocks.

Ordinary Kenyans

Justice Maraga made a name for himself amongst ordinary Kenyans because he always wanted his tenure to be judged, not by his peers, lawyers or the political elite, but rather by ordinary Kenyans. Justice Maraga has never laid claim nor shown any overt pretence of being a great jurist. But he is no fool. He always had his eyes on history and was troubled by the size of the shoes he inherited from his predecessor.

Instead, he wanted his tenure to be defined by the political consequences that are the by-product of cases decided in court. He also actions or spoke in a language that resonated with the average Kenyan. In the process he built his legacy on six pillars, each having ordinary Kenyans in mind.

First, he dimmed the lights on the Supreme Court as an institution and shone it on himself as a person. Justice Maraga’s calculation was simple. He knew he was incapable of writing blockbuster judgments that shake the country and move the tectonic plates of the legal and political plates and capture the aspiration and imagination of the country. Instead, he focused on politics and made the wars with the Executive the highlight of his tenure.

Second, the Supreme Court decision nullifying the presidential election in 2017 was calculated with a view to endearing himself to ordinary Kenyans. He learnt from the flak that former Chief Justice Willy Mutunga was subjected to by the opposition and the NGO world for the court’s 2013 decision that dismissed the opposition parties’ challenge to Mr Kenyatta’s victory. He was determined to build a populist base and the petition was a God sent opportunity.

Lack of depth

Third, Maraga built his reputation as a good Chief Justice premised on his Christian faith. The former CJ ring fenced himself with his religion and at times used it as a tactical alternative to the lack of depth in the philosophy of law. Religion was always a shield for himself, never a sword for the masses.

Fourth, he cleverly picked President Kenyatta as a bogeyman and addressed press conferences either to respond to him or challenge him to a duel. In a polarised and politically divided country, Justice Maraga deliberately targeted that part of Kenya that had no time for the President. The lack of chemistry and the mutual antipathy between the two helped him to initially court and keep a constituency that always rallied to his defence.

Five, the advice to the President asking him to disband Parliament was yet another bold political calculation on the part of Justice Maraga to paint himself as a hero that fights for ordinary Kenyans against corrupt and ineffective political elite. The advice was an important building block for Maraga’s legacy.

Six, Justice Maraga did not address corruption in the Judiciary. He never pioneered a single initiative to address the growing cancer that is corruption within the Judiciary.

This allowed him to unify members of the Judiciary behind him and sent loud messages to judges and magistrates that he had their back.

***

Next in this series: Ahmednasir Abdullahi’s views on former Chief Justice David Maraga’s key decisions and lawyer Sekou Owino defends Maraga’s legacy