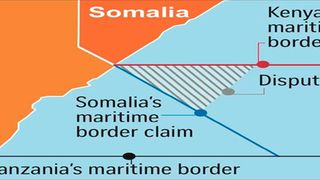

Kenya-Somalia maritime border dispute graphic.

| Joe Ngari | Nation Media GroupNews

Premium

What Kenya will lose to Somalia following judgment on maritime dispute

What you need to know:

- In its judgment, ICJ gave Somalia one of the seven offshore oil blocks that were under dispute.

- Judgment was largely in favour of Somalia as the court rejected most of the arguments advanced by Kenya.

Kenya will lose a rich section of the Indian Ocean that holds oil and gas deposits if the International Court of Justice’s (ICJ) judgment on the maritime border dispute with Somalia is enforced.

In a major blow to Kenya’s multibillion-shilling maritime economy, the court gave Somalia one of the seven offshore oil blocks that were under dispute, described as Block L-21.

It also transferred 280 kilometres of the ocean to Somalia. The loss leaves a narrow straight corridor of 75 kilometres to Kenya at 350 nautical miles.

Somalia will also seize 31,000-square kilometres of the maritime space that will reduce Kenya’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EZZ) at the sea to 121,000-square kilometres.

Kenya’s claim to the outer continental shelf will also be reduced to 41,000-square kilometres, as 61,000-square kilometres will be claimed by Somalia.

It’s a reality check for Nairobi as the full implications of the verdict emerge following an assessment by experts in the government.

“The effect of this is a narrow access that will severely limit our access to the ocean. The fear is that a vast area is left out of reach of Kenya’s surveillance that is a threat to security given the piracy and organised crime,” said a maritime expert.

“It (the judgment) poses an existential threat to Kenya. The judgment is a travesty of justice and it’s not enforceable by any sovereign state,” he added.

In favour of Somalia

The judgment was largely in favour of Somalia because the court rejected most of the arguments advanced by Kenya.

A sketch map of the new boundary proposed by the court shows geographically, Somalia did not win the ownership of the entire maritime area as it sought during the seven years of proceedings.

Apart from urging the court to determine the precise geographical co ordinates of the single maritime boundary in the sea, Somalia also wanted a finding that it fully owns six oil blocks identified as Blocks L 5, L 21, L 22, L 23, L 24 and L 25.

However, the court came up with new coordinates on the delimitation of the territorial sea and a base point placed on solid land on the mainland coasts of the two states. The base point will be used in setting the median line boundary.

The court observed that the course of the proposed median line corresponds closely to the course of a line “at right angles to the general trend of the coastline” that continues into the territorial sea.

Four years ago, Somalia attempted to auction off the oil blocks on the strength of a belief that it owns the region. It held an oil exploration exhibition in London in February, 2018, where the blocks were put up for sale to potential mineral explorers.

In its application filed in court in 2014, Mogadishu claimed that Kenya had acted unilaterally on the basis of its parallel boundary to exploit both the living and non living resources on Somalia’s side of a provisionally drawn equidistant line.

Maritime boundary

For example, it said Kenya had offered a number of petroleum exploration blocks that extend up to the northern limit of the parallel boundary. It said Kenya awarded Block L 5 to the American company Anadarko Petroleum Corporation in 2010.

Blocks L 21, L 23 and L 24 were awarded to the Italian company Eni S.p.A. in 2012, while Block L 22 was awarded to the French company Total S.A. the same year.

Somalia was laying claim of the area using a presidential decree and the Somali Maritime Law passed in 1989, which stated that the continental shelf of the war-torn nation extends throughout the natural prolongation of its land territory to the outer edge of the continental margin.

Kenya, on the other hand, argued that Somalia had ceded the blocks and accepted a maritime boundary at the parallel of latitude. Kenya referred, in particular, to the parties’ practice concerning naval patrols, fisheries, marine scientific research and oil concessions.

Kenya said Somalia acceded to the said boundary when it also failed to respond to two proclamations by Presidents Daniel arap Moi and Mwai Kibaki. One is dated February 28, 1979 and the other June 9, 2005.

It argued that the absence of protest in such circumstances constitutes acquiescence under international law.

Kenya added that Somalia had an internationally recognised government since 2000 which did not protest the proclamations issued by Moi and Kibaki, respectively.

But the court ruled that there is no compelling evidence that Somalia acquiesced to the maritime boundary claimed by Kenya and that, consequently, there is no agreed maritime boundary between the parties at the parallel of latitude.