Kenyatta and Moi made changes to suit their interests

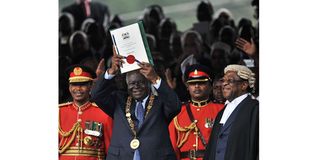

President Mwai Kibaki lifts up the new Constitution soon after its promulgation at the Uhuru Park grounds in Nairobi on August 27, 2010.

What you need to know:

- In his 15-year reign, Mzee Kenyatta oversaw 16 amendments against Moi’s 14 in 24 years.

- The fifth amendment, in 1966, required an MP who had resigned from the party that had sponsored him or her to Parliament to resign and seek fresh mandate.

- Former President Moi merely picked up from where Mzee had left.

Kenya’s four presidents have served through two constitutional dispensations, the Independence Constitution and the 2010 Constitution.

When it was written, the Independence Constitution provided for a multi-party system of government, parliamentary democracy and a federal structure of government.

It created a proper mechanisms for separation of powers; a bicameral legislative system; the Senate and the House of Representatives, and a dual executive where the Queen of England was the head of state and a Prime Minister as head of government.

It further divided the country into six regions, each with enormous powers. Executive power was vested in regional presidents and legislative power in the regional assemblies.

First President Mzee Jomo Kenyatta and his successor Daniel arap Moi served under this constitutional regime, while former President Mwai Kibaki ruled under both, taking the presidency in 2002 under the old constitutional order and later ushering in a new dispensation through the promulgation of the 2010 Constitution.

2010 Constitution

While the task of implementing the 2010 Constitution rests on the shoulders of President Uhuru Kenyatta, history suggests that respect for the rule of law and constitutionalism by the four leaders has been at a low level. “All the four presidents have shown a penchant for manipulating constitutional provisions or resisting change solely for political survival and to secure sectional interests,” says Maurice Odhiambo, the President of the National Civil Society Congress (NCSC).

Odhiambo led the Katiba Sasa Campaign, an initiative that made a significant contribution to realisation of the 2010 Constitution.

In his 15-year reign, Mzee Kenyatta oversaw 16 amendments against Moi’s 14 in 24 years.

Mzee launched the onslaught barely a year into office, dismantling the document and recreating the new Kenyan state to serve his interests.

The first amendment came in 1964, making Kenya a republic. It established the office of the President and repealed all provisions related to the office of the governor general.

All the powers of the office of the head of state and the office of the prime minister were transferred into the office of the President, making the holder both the head of state and head of government.

The executive authority of the six regional governments was extensively reduced in the same amendment, which also provided for a centralised disbursement of funds to counties.

The second amendment, in 1964, transferred to Parliament powers to alter regional boundaries and stopped independent sources of revenue to the regions, making them entirely dependent on funds from central government.

The amendment further redesignated regional presidents as regional chairmen, the appointment of judges was vested in the president and the requirement of the president to consult with at least four regional presidents over the appointment of the chief justice was removed.

The third amendment in 1965, lowered the majority required to vote in the Senate from 90 per cent to 65 per cent and in the House of representatives from 75 per cent to 65 per cent. The executive competence of the regions was deleted outright.

Parliamentary resolution

The period under which a parliamentary resolution to approve a declaration of state of emergency was increased from seven to 21 days and the majority of 65 per cent required reduced to a simple majority.

The fourth amendment in 1966, increased the powers of the president over the public service, declaring that all public officers were to hold office at the pleasure of the president.

Presidential powers to rule by decree in North Eastern Province (Garissa, Wajir and Mandera) were extended to Marsabit, Isiolo, Tana River and Lamu districts. It also decreed that MPs who failed to attend eight consecutive sittings in a session or were imprisoned for a period exceeding six months would lose their seats.

The fifth amendment, in 1966, required an MP who had resigned from the party that had sponsored him or her to Parliament to resign and seek fresh mandate.

The sixth amendment, also in 1966, amalgamated the Senate and the House of Representatives to establish the National Assembly. It increased the number of constituencies to 41 to accommodate members of the Senate in the new National Assembly. The composition of the Electoral commission was altered to provide for the speaker of the National Assembly as the chair, assisted by two appointees of the president.

In the tenth amendment, in 1968, the president was empowered to appoint members of the Public Service Commission, and given powers to nominate 12 members to the National Assembly. It removed the requirement of parliamentary approval for a state of emergency.

In the 11th amendment, in 1969, gave the president powers to appoint all members of the Electoral Commission.

The 15th amendment of 1975 extended the presidential prerogative to include annulling disqualification arising out of the report of an election court, following an election petition, where an election offence had been proved.

“Kenyatta Senior manipulated the Constitution many times. One of the recorded times was (what was referred to as) the Ngei amendment that allowed him to pardon (politician Paul) Ngei after he was convicted of an election offence,” Odhiambo says, referring to the 15th amendment.

University of Nairobi law scholar Wamitu Ndegwa says of Mzee Jomo Kenyatta: “He was above the law, including the Constitution.”

He adds: “He was always right and no court or judge dared to enforce the Constitution against his wishes.”

Political analyst Herman Manyora argues that Mzee was a centrist at heart and he could not countenance the idea of being guided by a document whose federalist ideals he did not espouse.

“Mzee had to dismantle the independence Constitution because it stood in the way of the imperial presidency he so badly wanted, and a unitary state which he believed in,” Manyora says.

Introduced Section 2A

Former President Moi merely picked up from where Mzee had left. The first two amendments under his leadership came less than a year into office.

But it is his third amendment in 1982 that turned the cause of Kenyan history and one which would eventually haunt him. The amendment introduced Section 2A that changed Kenya from the de facto (by fact) one party state system into a de-jure (by law) one party system. It also deleted the definition of political party and amended methods of nominations leading to a general election to make them a preserve of the ruling party Kanu.

The sixth amendment in 1986 removed the tenure of office of the offices of the Attorney-General and Controller and Auditor-General.

His seventh amendment made all offences punishable by death – murder, treason, robbery with violence – nonbailable.

The eighth amendment in 1988 empowered the police to detain suspects of capital offences for 14 days before taking them to court, and also removed security of tenure of members of the public service commission, judges of the High Court and the Court of Appeal.

Dr Ndegwa says that while Moi appreciated the force of the Constitution the respect was only to the extent where it served as an instrument for containing his competitors.

Manyora shares similar views: “He made Kanu so strong that he didn’t need any other organ of the state to govern.”

New document

For Odhiambo, the only reason those in power prefer a powerful centre is to extend patronage to their core supporters by opening up the taps of corruption.

Former President Kibaki took over in 2002 when the process to amend the Constitution was at its peak, and promised to deliver a new document within the first 100 days in office.

While Dr Ndegwa says Kibaki did not really need the constitution and it never really stood in his way on any major decision, Manyora and Odhiambo disagree. Manyora says the allure of a powerful presidency made Kibaki distance himself from reforms he had agitated while in the opposition.

Odhiambo says that, “even though Kibaki's tenure saw enactment of the 2010 constitution it is on record that he attempted to scuttle the constitution making process through the Wako Draft which was rejected in 2005.”

Manyora, Ndegwa and Odhiambo say Uhuru reluctantly supported the 2010 constitution and, therefore, cannot be relied upon to implement it.