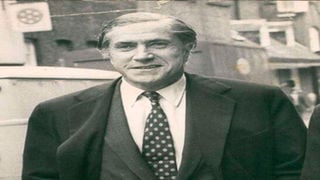

Tiny Rowland.

| File | Nation Media GroupPolitics

Premium

How Moi got entwined in Mozambique civil war through British businessman

What you need to know:

- Rowland was also using more than USD1 million every year to hire mercenaries to guard his militarised farms.

- Some people even thought Tiny Rowland got away with his corrupt dealings because Lonrho was a British intelligence front.

- Moi sent Bethuel Kiplagat to Gorongosa to meet Renamo leader Afonso Dhalakama.

- Kiplagat had to find his way through the Gorongosa bush to look for Dhlakama’s hideout.

In June 1985, as Mozambique celebrated its tenth anniversary of independence, British buccaneer Tiny Rowland was among the guests at the presidential dais.

He had flown to Mozambique to not buy a hotel and to cut peace agreements that would allow investors in a country torn apart by civil war.

More so, he was seeking to have African presidents start new alliances with apartheid South Africa.

That April, Rowland approached President Daniel arap Moi who agreed to host a team from South Africa in Kabarak, led by Rowland himself and his South African handler, Marquard de De Villiers, who controlled Lonhro’s interest in Pretoria and Maputo.

He also used to play golf with John Vorster, South Africa’s prime minister from 1966 to 1978.

The Kabarak meeting was one of many about the Maputo Peace Process as championed by Rowland.

Perfect middleman

In Africa, Rowland was always the perfect middleman and had got entangled in the civil wars of Mozambique and Angola, transporting weapons and brokering political deals.

He also had the ear of British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher who had refused to impose economic sanctions on the apartheid regime — seeking a negotiated end to the oppressive white rule instead.

Former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher who had refused to impose economic sanctions on the South African apartheid regime

Besides his friendship with President Moi, Rowland had unfettered access to Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) chief Bill Casey and the Mossad African operative David Kimche – well known in Kenya in the 1960s for taking some Mau Mau veterans, including General China, to Israel for military training.

Arms dealer Adnan Khashoggi whose ranch in Nanyuki was also used as a base for covert activities.

Others on Rowland’s phone book were arms dealer Adnan Khashoggi, whose ranch in Nanyuki was also used as a base for covert activities.

With all these, Rowland knew it would just be a matter of time to end the brutal civil war in Mozambique and secure his investments in southern Africa.

Link

During this period, according to declassified South African military memos, Rowland was the link between South Africans, National Union for the Total Liberation of Angola (Unita) rebel group leader Jonas Savimbi and US President Ronald Reagan’s advisers on Africa, including Chester Crocker, regarded as the architect of “constructive engagement” towards South Africa.

Jonas Savimbi who was Unita rebel group leader. He was killed in a battle against MPLA forces on February 22, 2002.

By being close to Thatcher and Rowland, President Moi was bound to be pulled into the South African circus — and he was, to an extent that he never left.

Thus, when Rowland suggested that Moi should have a secret meeting with him, De Villiers and the head of South Africa military intelligence, the Kenyan president agreed, according to Hennie Van Vuuren in his book Apartheid Guns and Money: A Tale of Profit quoting declassified South African military papers.

Tiny Rowland corrupted those who crossed his path.

Some people even thought Tiny Rowland got away with his corrupt dealings because Lonrho was a British intelligence front.

In March 1984, Rowland claimed, perhaps with some exaggerations, to have brought South Africa’s President P. W Botha and Mozambique’s Samora Machel to sign the controversial Nkomati Peace Accord at the South African town of Komatipoort, in which Machel was to expel African National Congress freedom fighters and South Africa was to stop financing Renamo guerrillas.

But Machel died in a plane crash on October 19, 1986 – in South Africa.

The country’s leadership was taken by Machel’s Foreign Affairs minister Joaquim Alberto Chissano before the full effect of Nkomati Pact could be felt.

Former Mozambique President Joaquim Chissano. In October 1988, Moi invited Chissano and Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe to Nairobi in a bid to explore alternatives for talks.

Two years later, in October 1988, Moi invited Chissano and Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe to Nairobi in a bid to explore alternatives for talks.

Some people say he was prodded by Tiny Rowland.

Meanwhile, Moi sent Bethuel Kiplagat, the Permanent Secretary for Foreign Affairs, to Gorongosa to meet Mozambique National Resistance (Renamo) leader Afonso Dhalakama, who had started travelling using a Kenyan passport.

It was Rowland who had brokered this initial meeting with Kiplagat; after all he bankrolled Renamo with payments of USD2 million per year to protect his Beira oil pipeline to independent Zimbabwe and which was Lonrho’s primary asset in Mozambique, according to celebrated author Alex Vines.

Bethuel Kiplagat, who in October 1990 flew to South Africa together with Rowland for a meeting with Foreign Affairs Minister Roelof Frederic “Pik” Botha.

Hire mercenaries

Rowland was also using more than USD1 million every year to hire mercenaries to guard his militarised farms.

Kiplagat had to find his way through the Gorongosa bush, as he would later recount, to look for Dhlakama’s hideout.

When they met, the guerrilla leader questioned ruling Mozambique Liberation Front (Frelimo)’s sincerity in ending the war, given that by that time, Dhlakama controlled most of the vast country apart from the capital city, Maputo.

From then on, and with the Kenyan passport, Dhlakama was able to travel and stay in Nairobi where the government secretly rented a house for him on Lenana Road and close to the Russian embassy.

Those who met him during this period, including Gen Daniel Opande, described Dhlakama as a “highly opinionated and most difficult to engage” guerilla leader.

Gen Opande had in 1990 been picked by President Moi to become military observer to the Maputo Peace Process – though with no brief on what his position entailed.

“I went without clear information about what was in store and how long my assignment would be,” he later wrote in his autobiography In Pursuit for Peace.

“My approach was to persuade him to remain in Nairobi, and to enter dialogue with key interlocutors.”

Kiplagat – or rather Moi – knew that without Rowland and South Africans, the quest for peace might not work.

That October, Kiplagat flew to South Africa together with Rowland for a meeting with Foreign Affairs Minister Roelof Frederic “Pik” Botha.

It was at this meeting that he encountered the man known as Rusty Evans – one of the most important bureaucrats in apartheid South Africa.

Former South African President Frederik Willem de Klerk. In June 1990, he flew to Kenya to discuss the Mozambique problem with Moi.

Kabarak meeting

After this meeting, Rowland convinced Botha and Evans to fly to Kabarak and meet President Moi.

So successful was the meeting that in June 1990, South African President Frederic Willem de Klerk flew to Kenya to discuss the Mozambique problem with Moi.

De Klerk also secretly met Dhlakama on June 8.

It was the first contact between independent Kenya and South Africa.

Apart from Rowland, Kiplagat was perhaps the most important person in the Maputo peace negotiations.

While Kiplagat was the master of diplomatic manoeuvres, Rowland had the money.

On June 12, 1990 for instance, Kiplagat accompanied the Renamo leader from Nairobi aboard Rowland’s jet to Blantyre, Malawi, where direct talks between him and Chissano were expected to start.

There were many more clandestine meetings that followed.

In August 1990, according to Africa Confidential newsletter, Moi sent Gen Augustine Cheruiyot, commander of the Kenyan Defence College, to meet Dhlakama after entering Mozambique through southern Malawi.

It was Kiplagat, however, who convinced Dhlakama to sign several agreements that would open the Beira corridor.

Declare a ceasefire

“Ambassador Kiplagat pointed out to him that the only way he could prove he was controlling the large expanse of northern Mozambique was by declaring a ceasefire along the corridor. If the ceasefire held, the international community might begin to talk to Renamo and convince Frelimo to do the same,” Opande later wrote.

Rowland had by this time moved his headquarters to Nairobi and appointed Mark Too as the chairman of Lonrho East Africa.

Interestingly, Mark Too was also included in the Maputo talks.

Gen Opande described him as a “very close confidant of several African leaders…a brilliant negotiator and had the memory of an elephant”.

Other entrants into these talks were US Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs Herman Cohen, who met President Moi about Rowland’s initiative – even though America was also pursuing other efforts.

The US had learnt how to deal with Maputo since early March 1981 when six Americans were expelled from Mozambique on espionage charges.

The diplomats flew to Kenya as the then Marxist-Leninist nation claimed that it had broken up a CIA ring.

Those expelled included second secretaries Frederick Boyce Lundahl and Louis Leon Olivier and a political officer Patricia Russel.

The State Department blamed Cuban intelligence agents for being behind the expulsion order.

It said two Cuban intelligence officers – Armnado Fernandez and Manuel Galan – had forcibly detained an American embassy officer “while they attempted to recruit him as a spy for Cuba”.

President Reagan was hardly three months in office when this happened and some diplomats suggested that it was a warning to him not to adopt a pro-South Africa stance in the White House.

But it was the Tiny Rowland’s initiative which was brokered by Moi and Kiplgat to a large extent that would later bring peace – somehow.