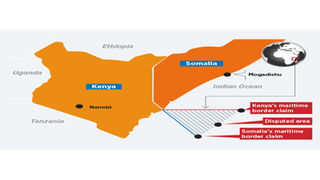

The area in the Kenya-Somalia maritime border dispute forms a triangle east of the Kenya coast.

|News

Premium

Kenya’s options in sea border dispute with Somalia

Legal experts say Kenya has multiple options for dealing with a recent adverse judgment of a top world court on the maritime dispute with Somalia instead of the open defiance.

The International Court of Justice (ICJ) on October 14 gave Somalia more than 70 per cent of a disputed Indian Ocean area that measures 100,000 square kilometres and is believed to be rich in natural oil and gas reserves.

Lawyers say that among Kenya’s options is seeking a revision of the judgment through the United Nations Security Council, leveraging its regional influence to frustrate the adoption of the judgment or using diplomacy.

Nairobi, they say, can also frustrate implementation of the judgment by departing from its foreign policy that has enabled the stability of Somalia’s federal government.

Article 61 of the ICJ statute allows the filing of a request for revision a judgment but only when “it is based on the discovery of a fact, taken as decisive, that, when the judgment was delivered, was unknown to the court and also to the party claiming revision, and such lack of knowledge was not due to negligence”.

Such a request must be made within six months of discovering the new fact.

"The UN Security Council chair for the month of October is President Uhuru Kenyatta. He should seize that opportunity and bring to the attention of the UN top organ that implementation of the ICJ judgment has security ramifications," lawyer Kamotho Njenga says.

"He ought to push for an application of revision and see whether the dispute can be resolved in any other manner, such as negotiations."

Because the coordinates of the new boundary proposed by the court are on the land territory, Mr Njenga says, the court should be informed that altering Kenya's territorial boundary requires the involvement of citizens through a referendum.

The UN court must, therefore, address the conflict between international maritime laws and local laws and determine whether it can upstage and disregard Kenya's Constitution.

The court’s decision followed a request from the Somalia government in its case against Kenya for the principal judicial organ of the UN to redraw the sea boundary.

The new boundary gives Somalia territorial rights over a large portion of the disputed maritime area as it gained several offshore oil exploration blocks previously claimed by Nairobi.

"Kenya argues that the judgment is literally unenforceable. It should request the UN Security Council to make an application for revision and interpretation of the judgment raising questions on how the judgment will be implemented because the judges altered the territory of a sovereign country," Mr Njenga says.

"Since Kenya's Constitution says the alteration of the territory requires an amendment to the Constitution and the same can only be approved by the people through a referendum (Article 255(1)(b), is the court literally ordering a referendum to adjust the territory of Kenya?" Mr Njenga asks.

Kenya can also exploit other avenues, such as negotiations and lodging a separate case at the continental level with the African Union.

But lawyer Kibe Mungai says negotiations may not be easy, as Somalia is holding a judgment rendered by a top world top court in its favour and diplomacy will be a political process.

Somalia, however, may yield to compromise considering Kenya contributes to the stability of the federal government in Mogadishu and hosts Somali refugees who fled the civil war, he says.

"That is one way of exercising and leveraging power against Somalia, which is almost a failed state were it not for the support of the Kenyan government,” Mr Mungai says.

“If Kenya withdraws its foreign policy to help the federal government of Somalia, the Somalia government will collapse. In such an event, there will be no judgment holder," says.

He adds that if Kenya withdraws, that will also make life difficult for Somalia economically, especially considering the standoff between Somalia’s government and the semiautonomous Jubbaland region.

Mr Mungai observes that Kenya can marshal international support to put pressure on Somalia.

"Relations between states are governed by the relative power of each. Kenya, using its power and making it clear that the judgment is not enforceable, can bring Somalia to negotiations with a view to compromising on the ICJ judgment," he says.

"However, it is a long shot to expect that diplomatic efforts will change the position of Somalia in regard to ownership of the disputed maritime area."