Bar raised for law students in course reforms

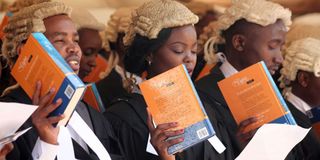

New advocates being admitted to the roll at the Supreme Court Building last year.

What you need to know:

- Bar examinations that have persistently recorded high failure rates are also changing.

- Content of the curriculum that prepares the candidates to join the roll of advocates has been trimmed, rationalised and reorganised to conform to the industry needs.

A multiple of factors that are at play are curriculum content, teaching methodologies, staffing, resources and examinations.

Lawyers’ training is gearing for a turnaround following a review and implementation of a new curriculum. Bar examinations that have persistently recorded high failure rates are also changing.

These follow widespread concerns about professional training of lawyers at the Kenya School of Law (KSL) and particularly low performance of the candidates in the bar exams, yet they have completed university education.

A new and revised curriculum has been developed and is being rolled out at KSL. It will be tested for the first time next year. In fact, were it not for Covid-19, which led to closures of all educational institutions, it would have been tested this year.

Content of the curriculum that prepares the candidates to join the roll of advocates has been trimmed, rationalised and reorganised to conform to the industry needs.

This opens a new chapter in legal training. In recent years, the Kenya School of Law, which is the trainer, and the Council of Legal of Education (CLE), regulator and examiner, have found themselves under fire over high failure rate of students in the professional examinations that lead to admission to the bar.

Bar examinations

Petitions have variously been filed in the National Assembly, Senate and courts over students’ poor performance in the bar examinations. However, lost in the petitions is critical interrogation of the complexities in legal training and examination and as well as the governing laws, some overlapping with other existing pieces of legislations.

In separate interviews, the director of the Kenya School of Law, Dr Henry Mutai, and the chief executive of CLE, Dr Jacob Gakeri, explained the measures being undertaken to redress the challenges confronting legal training and the exams. They noted that some of the issues are historical and have to be addressed within a broader context.

To resolve some of the issues, KSL commissioned the Kenya Institute for Public Policy Research and Analysis, which produced an informative report spotlighting the factors influencing students’ performance in the bar examinations.

A multiple of factors that are at play are curriculum content, teaching methodologies, staffing, resources and examinations.

The Advocates Training Programme (ATP) formally runs for 18 months, consisting of 12 months of instructions and six for pupillage. In total, the programme has nine courses. Unlike other training programmes, here the courses are prescribed in law - Legal Education Act, 2012 - and include criminal litigation, civil litigation, professional ethics and practice, and commercial transactions.

The latter is one of the courses that have been redesigned. It had been faulted for being heavily loaded and duplicating units already covered at the university. Now, it has been trimmed and units that are offered in universities knocked out.

For starters, legal training is compromised right at the university level. There are 15 universities offering law degree programmes but from Kippra study, it emerged that some of these institutions have been admitting students who were not qualified, especially before 2016 when institutions used to offer bridging courses to upgrade those who had low grades in Form Four examinations.

Minimum qualifications

Moreover, there are reservations even among those who qualify because some have just the minimum qualifications and in ideal situation, are not suited for law programmes. Generally, admission to university is pegged at C+ grade at the Kenya Certificate of Secondary Education plus B grade in English and Kiswahili.

So, on paper, any candidate with such qualification is admissible to a law degree course but may not have the aptitude and capacity for the programme.

The Kippra study demonstrated this, showing how those who had high grades at KCSE, A or A-, had higher pass rates at the bar exams compared to those with C+ grade, indicating positive correlation between performance in high school and at KSL.

The second challenge is the content and calibre and adequacy of teaching staff at KSL. Dr Mutai acknowledged that the school did not have sufficient number of lecturers due to cash constraints and because of that, had to rely on adjuncts most of whom were practising lawyers and, who, sometimes, found themselves engaged in court, hence unable to give full attention to the learners.

Moreover, the facilities had been stretched to the limit due to the increased numbers of students. To be sure, all the universities offering degree programmes churn out graduates every year and all of them, plus those from foreign universities, have to go through KSL for the professional programme. So, whereas the law graduates have been on the rise, facilities at KSL have not expanded in equal measure.

“Given the rising numbers of lawyers qualifying from the universities, we have been forced to increased admissions and that impacts on facilities and resources,” says Dr Mutai. “We have been forced to expand class sizes and that compromises quality teaching and learning.”

Third, which is most pressing, is performance in the bar examinations. In terms of organisation, the exams are divided into three components, namely, project, orals and written. Project and orals are formative exams done at KSL but moderated by CLE and constitute 40 per cent of the marks. Written exams are summative and administered by CLE and carries 60 marks.

Oral exams

Some of the concerns raised were that oral exams were broad and unscripted, which made it difficult for students to prepare appropriately. Another grouse was that the written exams were beyond the scope of what was taught, leading to high failure rates. These are some of the insights that informed revision of curriculum and testing.

Both Dr Mutai and Dr Gakeri were upbeat that the revisions of the curriculum and implementation of some of the recommendations of the Kippra study will go a long way to improve students’ performance in the bar examinations.

“We worked together in revising the curriculum, involving students and all stakeholders, to plug the gaps and ensure proper alignment with the industry requirements,” said Dr Gakeri.

Yet there are other vexing matters in legal training. Among these is the duplication of roles of CLE and other higher education regulators such as the Commission for University Education and the Kenya National Qualifications Authority in regard to licensing, supervising and enforcing quality standards. Only in June, the High Court ruled that all matters related to licensing university programmes is a preserve of CUE.

The emerging picture is that legal training is a complex system with multiple layers of issues which, although have been interrogated at different times in the past, have not been dealt with resolutely and definitively.