Why literature curriculum must join the 21st century

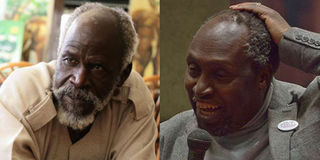

Writer and poet Taban Lo Liyong (left) and Prof Ngugi wa Thion'go.

As I suggested last week, the world of letters widely recognises, rightly in my view, that Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, in partnership with Owuor Anyumba and Taban Lo Liyong, initiated and oversaw an important revolution in how the teaching of literature in universities in Africa should be structured, if the curriculum is to mediate communication between the people and their immediate or broader environment.

Not only did the three destabilise the intellectual platform on which the colonial project had been mounted, thus, the indoctrination on the nature of knowledge and civilisation, and their manifestation as and in literature, they also introduced an important trope by which later debates on the thought patterns of continental and diasporic Africans could be held.

The trope of decolonisation, which was popularised by Ngũgĩ’s 1986 essays, continues to capture the imagination of many scholars who view the legacies of colonial domination as largely responsible for the continued inequalities that damn some people to lives of misery while rigging opportunities in favour of a small elite.

In all these, the grammar of decolonisation, which animated the Ngũgĩ-Anyumba-Taban initiative, finds relevance among those of us who still think that despite the initial triumphs of anti-colonial initiatives, classical colonialism only retreated to repackage, and is now back in other equally vicious but relatively subtle forms that rely on what appear fair and objective forms.

I am talking about the seemingly universal acquiescence to the force of neoliberal market machinations to extend racialised and gendered inequalities – leave room for a few exceptions – while propping up many unhelpful myths, such as that hard work is a precondition for material success. We now know that this is hogwash, because generally people inherit the blessings of privilege or the curses of poverty and, however far they may run, they never quite break off the chains.

Sisyphean struggles

Part of these Sisyphean struggles by human beings to find their level at the market place have seen humanity become more reckless in their dealings with the earth, for example, leading to wanton extraction that has led to the unfortunate and now undeniable tragedy of global warming, whose ramifications we are yet to understand fully.

As Cameroonian philosopher Achille Mbembe noted in a recent lecture, the earth is hurting and in dire need for repair. To Mbembe, significant changes beneath the surface of the earth are diminishing its capacity to carry us on its shoulders, and soon we shall be unable to pin it beneath our feet.

If one needed more evidence of this, they only need to look at the plight of our compatriots in Baringo, who have to leave their earthly achievements to flee uphill from raging water levels.

So, what has the revolution of literature curriculums at the university level got to do with all these? One, the current trajectory and underpinning philosophies of literature have a narrower scope and vision that tend to prioritise rather dated concerns. For example, the overarching ideological frame of the 1960s when the Ngũgĩ-Anyumba-Taban partnership inaugurated the curriculum decolonisation agenda was largely predicated on a biological fiction of race that was measured, almost exclusively, using phenotypic indicators of the colour of one’s skin, eyes, or hair.

What happens now, given that race and racism have been relocated beneath the skin, when pretensions of post-racialism go hand in hand with racial profiling in transit points such as airports?

What kind of literature should we teach that adequately prepares our students to appreciate and push back against normalised forms of exclusion and marginalisation?

These and related questions demand that we look at the literature curriculum more closely to imagine possibilities of centering new genres of literature that allow our students to enjoy the magic of literary creativity while learning how technology has been appropriated to extend racial and other inequalities. So, for instance, where we had the African Novel as the ultimate literary unit at college, how about a unit in Sci-Fi?

After all, the biosphere that was the reason colonialism was attractive to Europe, and what informed the hunger for European imperialism generally, was the desire to ‘own’ and control part of a biosphere that has now been so ravaged by industrial capitalism to the extent that not much of the earth is now habitable without modification.

The daily fog of India’s and China’s cities attest to this. Clearly, we need to focus on a literature that appreciates historical concerns but also prepares our learners to ask the right questions to fit meaningfully in the current world of technology, travel, and reconfigured value systems. This way, it should be possible for us to mount literature units that illuminate ecological and other concerns aimed at ensuring sustainable existence in the biosphere.

Reading literature

Second, the need to revolutionise the literature curriculum is informed by the concerns with the value of the discipline in the prevailing circumstances where people pursue education for utilitarian purposes, primarily for employment. Why should a student spend years reading literature from Classical Greek days to current urban legends when all they really want is to meet credit requirements for a BA, after which they proceed to be bank tellers, among other openings? Shouldn’t it be possible to tailor units such as Literature for Engineering? Or Literature and Legal Reasoning?

I have it said by many colleagues that literature is useful in equipping learners with critical thinking skills. This is definitely true, but how do we proceed in an era when algorithmic and other forms of artificial intelligence are becoming increasingly available and affordable?

It is clear to me that literature is an important subject that, if I had my way, every professional would be required study. But I also think it should not be curated in a rigid or one-size-fits-all approach. Instead, the curriculum could be rejigged to accommodate different interest groups; those who have a passing interest in it need not be taken through the whole nine yards just.

Indeed, given the reality that most people in the world have bought into the trap of neoliberal economics – in which STEM is touted as the panacea to all problems of underdevelopment and personal achievement, it is time we thought of packaging literature in ways that meet our and ‘their’ needs. That is the only way that we can alter the pro-market thinking that privileges STEM and business courses at the expense of the humanities, including literature.

That is the only way that we can complete the project of decolonisation that Ngũgĩ-Anyumba-Taban crew initiated. At the core of this strand of decolonisation is the idea that we need a radical openness of discipline, as opposed to the implied insulation that made literature attractive to the ideologues of yore and dreadful to repressive regimes of the 60s and 70s.

That double attribute, of attraction to progressive minds and repulsive to reactionary ones, is what ultimately made it marginal in the preeminent neoliberal world of thought. It is what, logically, complete decolonization can cure.